Chapter: Introduction to the Design and Analysis of Algorithms : Decrease and Conquer

Insertion Sort

Insertion

Sort

In this

section, we consider an application of the decrease-by-one technique to sorting

an array A[0..n − 1]. Following the technique’s

idea, we assume that the smaller problem of sorting the array A[0..n − 2] has already been solved to

give us a sorted array of size n − 1: A[0] ≤ .

. . ≤ A[n − 2]. How can we take advantage of

this solution to the smaller problem to get a solution to the original problem

by taking into account the element A[n − 1]?

Obviously, all we need is to find an appropriate position for A[n − 1] among the sorted elements and

insert it there. This is usually done by scanning the sorted subarray from

right to left until the first element smaller than or equal to A[n − 1] is encountered to insert A[n − 1] right after that element. The

resulting algorithm is called straight insertion sort or simply insertion

sort.

Though

insertion sort is clearly based on a recursive idea, it is more efficient to

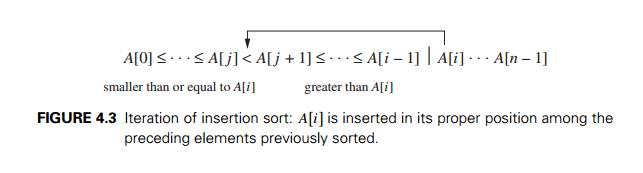

implement this algorithm bottom up, i.e., iteratively. As shown in Figure 4.3,

starting with A[1] and

ending with A[n − 1],

A[i] is inserted in its appropriate

place among the first i elements

of the array that have been already sorted (but, unlike selection sort, are

generally not in their final positions).

Here is

pseudocode of this algorithm.

ALGORITHM InsertionSort(A[0..n − 1])

//Sorts a

given array by insertion sort

//Input:

An array A[0..n − 1] of n orderable elements //Output:

Array A[0..n − 1] sorted in nondecreasing order

for i ← 1 to n − 1 do

v ← A[i]

j ← i − 1

while j ≥ 0 and A[j ] >

v do

A[j

+ 1]

← A[j

] j ← j − 1

A[j

+ 1]

← v

The

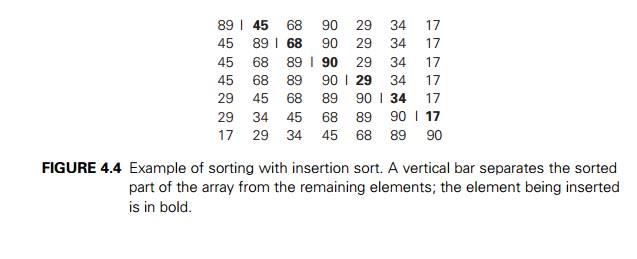

operation of the algorithm is illustrated in Figure 4.4.

The basic

operation of the algorithm is the key comparison A[j ] >

v. (Why not j ≥ 0? Because it is almost certainly

faster than the former in an actual computer

implementation.

Moreover, it is not germane to the algorithm: a better imple-mentation with a

sentinel—see Problem 8 in this section’s exercises—eliminates it altogether.)

The

number of key comparisons in this algorithm obviously depends on the nature of

the input. In the worst case, A[j ] >

v is executed the largest number of times, i.e., for every j = i − 1, . . . , 0. Since v = A[i], it

happens if and only if A[j ]

> A[i] for

j = i − 1, . . . , 0. (Note that we are using the

fact that on the ith iteration of insertion sort all

the elements preceding A[i] are the first i elements in the input, albeit in

the sorted order.) Thus, for the worst-case input, we get A[0] > A[1] (for i = 1), A[1]

> A[2] (for i = 2),

. . . , A[n − 2]

> A[n − 1] (for i = n − 1). In other words, the worst-case

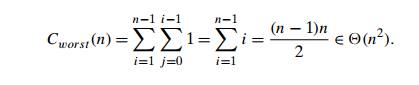

input is an array of strictly decreasing values. The number of key comparisons

for such an input is

Thus, in

the worst case, insertion sort makes exactly the same number of compar-isons as

selection sort (see Section 3.1).

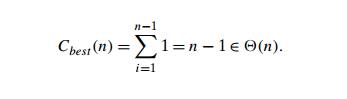

In the

best case, the comparison A[j ] >

v is executed only once on every iteration of the outer loop. It happens

if and only if A[i − 1] ≤ A[i] for every i = 1, . . . , n − 1, i.e., if the input array is

already sorted in nondecreasing order.

(Though

it “makes sense” that the best case of an algorithm happens when the problem is

already solved, it is not always the case, as you are going to see in our

discussion of quicksort in Chapter 5.) Thus, for sorted arrays, the number of

key comparisons is

This very

good performance in the best case of sorted arrays is not very useful by

itself, because we cannot expect such convenient inputs. However, almost-sorted

files do arise in a variety of applications, and insertion sort preserves its

excellent performance on such inputs.

A

rigorous analysis of the algorithm’s average-case efficiency is based on

investigating the number of element pairs that are out of order (see Problem 11

in this section’s exercises). It shows that on randomly ordered arrays,

insertion sort makes on average half as many comparisons as on decreasing

arrays, i.e.,

This

twice-as-fast average-case performance coupled with an excellent efficiency on

almost-sorted arrays makes insertion sort stand out among its principal

com-petitors among elementary sorting algorithms, selection sort and bubble

sort. In addition, its extension named shellsort, after its inventor D. L.

Shell [She59], gives us an even better algorithm for sorting moderately large

files (see Problem 12 in this section’s exercises).

Exercises

4.1

1. Ferrying soldiers A

detachment of n soldiers

must cross a wide and deep river with

no bridge in sight. They notice two 12-year-old boys playing in a rowboat by

the shore. The boat is so tiny, however, that it can only hold two boys or one

soldier. How can the soldiers get across the river and leave the boys in joint

possession of the boat? How many times need the boat pass from shore to shore?

2. Alternating

glasses

There are 2n glasses

standing next to each other in a row, the first n of them

filled with a soda drink and the remaining n glasses

empty. Make the glasses alternate in a filled-empty-filled-empty pattern in the

minimum number of glass moves. [Gar78]

Solve the same problem if 2n glasses—n with a drink and n empty—are initially in a random

order.

3. Marking cells Design an algorithm for the

following task. For any even n, mark n cells on an infinite sheet of

graph paper so that each marked cell has an odd number of marked neighbors. Two

cells are considered neighbors if they are next to each other either

horizontally or vertically but not diagonally. The marked cells must form a

contiguous region, i.e., a region in which there is a path between any pair of

marked cells that goes through a sequence of marked neighbors. [Kor05]

4. Design a decrease-by-one algorithm for generating

the power set of a set of n

elements. (The power set of a set S is the

set of all the subsets of S,

including the empty set and S itself.)

5. Consider the following algorithm to check

connectivity of a graph defined by its adjacency matrix.

ALGORITHM Connected(A[0..n − 1, 0..n − 1])

//Input:

Adjacency matrix A[0..n − 1, 0..n − 1]) of an

undirected graph G

//Output: 1 (true) if G is

connected and 0 (false) if it is not

if n = 1 return 1 //one-vertex graph

is connected by definition

else

if not Connected(A[0..n − 2, 0..n − 2]) return 0 else for j ← 0 to n − 2 do

if A[n − 1, j ] return 1 return 0

Does this

algorithm work correctly for every undirected graph with n > 0 vertices? If you answer yes,

indicate the algorithm’s efficiency class in the worst case; if you answer no,

explain why.

7.

Team

ordering You have the results of a completed round-robin tournament in which n teams

played each other once. Each game ended either with a victory for one of the

teams or with a tie. Design an algorithm that lists the teams in a sequence so

that every team did not lose the game with the team listed immediately after

it. What is the time efficiency class of your algorithm?

8. Apply insertion sort to sort the list E, X, A, M, P , L, E in alphabetical order.

a. What

sentinel should be put before the first element of an array being sorted in order to avoid checking the

in-bound condition j ≥ 0 on each iteration of the inner

loop of insertion sort?

b. Is the sentinel version in the

same efficiency class as the original version?

9. Is it possible to implement insertion sort for

sorting linked lists? Will it have the same O(n2) time

efficiency as the array version?

10. Compare the text’s implementation of insertion sort

with the following ver-sion.

ALGORITHM InsertSort2(A[0..n − 1])

for i ← 1 to n − 1 do j ← i − 1

while j ≥ 0 and A[j ] >

A[j + 1] do swap(A[j ], A[j + 1])

j ← j – 1

What is

the time efficiency of this algorithm? How is it compared to that of the

version given in Section 4.1?

11. Let A[0..n − 1] be an

array of n sortable elements. (For

simplicity, you may assume that all the elements are distinct.) A pair (A[i], A[j ]) is called an inversion

if i < j and A[i] > A[j ].

What arrays of size n have the

largest number of inversions and what is this number? Answer the same questions

for the smallest number of inversions.

Show that the average-case number of key

comparisons in insertion sort is given by the formula

12. Shellsort (more accurately Shell’s sort) is an

important sorting algorithm that works by applying insertion sort to each of

several interleaving sublists of a given list. On each pass through the list,

the sublists in question are formed by stepping through the list with an

increment hi taken

from some predefined decreasing sequence of step sizes, h1 > .

. . > hi > .

. . > 1, which must end with 1. (The

algorithm works for any such sequence, though some sequences are known to yield

a better efficiency than others. For example, the sequence 1, 4, 13, 40, 121, .

. . , used, of course, in reverse, is known to be among the best for this

purpose.)

a. Apply

shellsort to the list

S, H, E, L, L, S, O, R, T , I, S, U, S, E, F, U,

L

Is shellsort a stable sorting algorithm?

Implement shellsort, straight insertion sort,

selection sort, and bubble sort in the language of your choice and compare

their performance on random arrays of sizes 10n for n = 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6 as

well as on increasing and decreasing arrays of these sizes.

Related Topics