Chapter: Security in Computing : Legal and Ethical Issues in Computer Security

Information and the Law

Information and the Law

Source code, object code, and

even the "look and feel" of a computer screen are recognizable, if

not tangible, objects. The law deals reasonably well, although somewhat

belatedly, with these things. But computing is in transition to a new class of

object, with new legal protection requirements. Electronic commerce, electronic

publishing, electronic voting, electronic bankingthese are the new challenges

to the legal system. In this section we consider some of these new security

requirements.

Information as an Object

The shopkeeper used to stock

"things" in the store, such as buttons, automobiles, and pounds of

sugar. The buyers were customers. When a thing was sold to a customer, the

shopkeeper's stock of that thing was reduced by one, and the customer paid for

and left with a thing. Sometimes the customer could resell the thing to someone

else, for more or less than the customer originally paid.

Other kinds of shops provided

services that could be identified as things, for example, a haircut, root

canal, or defense for a trial. Some services had a set price (for example, a

haircut), although one provider might charge more for that service than

another. A "shopkeeper" (hair stylist, dentist, lawyer) essentially

sold time. For instance, the price of a haircut generally related to the cost

of the stylist's time, and lawyers and accountants charged by the hour for

services in which there was no obvious standard item. The value of a service in

a free economy was somehow related to its desirability to the buyer and the

seller. For example, the dentist was willing to sell a certain amount of time,

reserving the rest of the day for other activities. Like a shopkeeper, once a

service provider sold some time or service, it could not be sold again to

someone else.

But today we must consider a

third category for sale: information. No one would argue against the

proposition that information is valuable. Students are tempted to pay others

for answers during examinations, and businesses pay for credit reports, client

lists, and marketing advice. But information does not fit the familiar

commercial paradigms with which we have dealt for many years. Let us examine

why information is different from other commercial things.

Information Is Not Depletable

Unlike tangible things and

services, information can be sold again and again without depleting stock or

diminishing quality. For example, a credit bureau can sell the same credit

report on an individual to an unlimited number of requesting clients. Each

client pays for the information in the report. The report may be delivered on

some tangible medium, such as paper, but it is the information, not the medium,

that has the value.

This characteristic separates

information from other tangible works, such as books, CDs, or art prints. Each

tangible work is a single copy, which can be individually numbered or accounted

for. A bookshop can always order more copies of a book if the stock becomes

depleted, but it can sell only as many copies as it has.

Information Can Be Replicated

The value of information is

what the buyer will pay the seller. But after having bought the information,

the buyer can then become a seller and can potentially deprive the original

seller of further sales. Because information is not depletable, the buyer can

enjoy or use the information and can also sell it many times over, perhaps even

making a profit.

Information Has a Minimal Marginal Cost

The marginal cost of an item is the cost to produce another one after

having produced some already. If a newspaper sold only one copy on a particular

day, that one issue would be prohibitively expensive because it would have to

cover the day's cost (salary and benefits) of all the writers, editors, and

production staff, as well as a share of the cost of all equipment for its

production. These are fixed costs needed to produce a first copy. With this

model, the cost of the second and subsequent copies is minuscule, representing

basically just the cost of paper and ink to print them. Fortunately, newspapers

have very large press runs and daily sales, so the fixed costs are spread

evenly across a large number of copies printed. More importantly, publishers

have a reasonable idea of how many copies will sell, so they adjust their budgets

to make a profit at the expected sales volume, and extra sales simply increase

the profit. Also, newspapers budget by the month or quarter or year so that the

price of a single issue does not fluctuate based on the number of copies sold

of yesterday's edition.

In theory, a purchaser of a

copy of a newspaper could print and sell other copies of that copy, although

doing so would violate copyright law. Few purchasers do that, for four reasons.

The newspaper is covered by

copyright law.

The cost of reproduction is

too high for the average person to make a profit.

It is not fair to reproduce

the newspaper that way.

There is usually some quality

degradation in making the copy.

Unless the copy is truly

equivalent to the original, many people would prefer to buy an authentic issue

from the news agent, with clear type, quality photos, actual color, and so

forth.

The cost of information

similarly depends on fixed costs plus costs to reproduce. Typically, the fixed

costs are large whereas the cost to reproduce is extremely small, even less

than for a newspaper because there is no cost for the raw materials of paper

and ink. However, unlike a newspaper, information is far more feasible for a

buyer to resell. A copy of digital information can be perfect, indistinguishable

from the original, the same being true for copies of copies of copies of

copies.

The Value of Information Is Often Time Dependent

If you knew for certain what

the trading price of a share of Microsoft stock would be next week, that

information would be extremely valuable because you could make an enormous

profit on the stock market. Of course, that price cannot be known today. But

suppose you knew that Microsoft was certain to announce something next week

that would cause the price to rise or fall. That information would be almost as valuable as knowing

the exact price, and it could be known in advance. However, knowing yesterday's

price for Microsoft stock or knowing that yesterday Microsoft announced

something that caused the stock price to plummet is almost worthless because it

is printed in every major financial newspaper. Thus, the value of information

may depend on when you know it.

Information Is Often Transferred Intangibly

A newspaper is a printed

artifact. The news agent hands it to a customer, who walks away with it. Both

the seller and the buyer realize and acknowledge that something has been

acquired. Furthermore, it is evident if the newspaper is seriously damaged; if

a serious production flaw appears in the middle, the defect is easy to point

out.

But times are changing.

Increasingly, information is being delivered as bits across a network instead

of being printed on paper. If the bits are visibly flawed (that is, if an error

detecting code indicates a transmission error), demonstrating that flaw is

easy. However, if the copy of the information is accurate but the underlying

information is incorrect, useless, or not as expected, it is difficult to

justify a claim that the information is flawed.

Legal Issues Relating to Information

These characteristics of

information significantly affect its legal treatment. If we want to understand

how information relates to copyright, patent, and trademark laws, we must

understand these attributes. We can note first that information has some, limited

legal basis for the protection. For example, information can be related to

trade secrets, in that information is the stock in trade of the information

seller. While the seller has the information, trade secret protection applies

naturally to the seller's legitimate ability to profit from information. Thus,

the courts recognize that information has value.

However, as shown earlier, a

trade secret has value only as long as it remains a secret. For instance, the

Coca-Cola Company cannot expect to retain trade secret protection for its

formula after it sells that formula. Also, the trade secret is not secure if

someone else can derive or infer it.

Other forms of protection are

offered by copyrights and patents. As we have seen earlier, neither of these

applies perfectly to computer hardware or software, and they apply even less

well to information. The pace of change in the legal system is slow, helping to

ensure that the changes that do occur are fair and well considered. The

deliberate pace of change in the legal system is about to be hit by the

supersonic rate of change in the information technology industry. Laws do not,

and cannot, control all cyber threats. Let us look at several examples of

situations in which information needs are about to place significant demands on

the legal system.

Information Commerce

Information is unlike most

other goods traded, even though it has value and is the basis of some forms of

commerce. The market for information is still young, and so far the legal

community has experienced few problems. Nevertheless, several key issues must

be resolved.

For example, we have seen

that software piracy involves copying information without offering adequate

payment to those who deserve to be paid. Several approaches have been tried to

ensure that the software developer or publisher receives just compensation for

use of the software: copy protection, freeware, and controlled distribution.

More recently, software is being delivered as mobile code or applets, supplied

electronically as needed. The applet approach gives the author and distributor

more control. Each applet can potentially be tracked and charged for, and each

applet can destroy itself after use so that nothing remains to be passed for

free to someone else. But this scheme requires a great deal of accounting and

tracking, increasing the costs of what might otherwise be reasonably priced.

Thus, none of the current approaches seem ideal, so a legal remedy will often

be needed instead of, or in addition to, the technological ones.

Electronic Publishing

Many newspapers and magazines

post a version of their content on the Internet, as do wire services and

television news organizations. For example, the British Broadcasting Company

(BBC) and the Reuters news services have a significant web presence. We should

expect that some news and information will eventually be published and

distributed exclusively on the Internet. Indeed, encyclopedias such as the

Britannica and Expedia are mainly web-based services now, rather than being delivered

as the large number of book volumes they used to occupy. Here again the

publisher has a problem ensuring that it receives fair compensation for the

work. Cryptography-based technical solutions are under development to address

this problem. However, these technical solutions must be supported by a legal

structure to enforce their use.

Protecting Data in a Database

Databases are a particular

form of software that has posed significant problems for legal interpretation.

The courts have had difficulty deciding which protection laws apply to

databases. How does one determine that a set of data came from a particular

database (so that the database owner can claim some compensation)? Who even

owns the data in a database if it is public data, such as names and addresses?

Electronic Commerce

Laws related to trade in

goods have evolved literally over centuries. Adequate legal protections exist

to cover defective goods, fraudulent payment, and failure to deliver when the

goods are tangible and are bought through traditional outlets such as stores

and catalogs. However, the situation becomes less clear when the goods are

traded electronically.

If you order goods

electronically, digital signatures and other cryptographic protocols can

provide a technical protection for your "money." However, suppose the

information you order is not suitable for use or never arrives or arrives

damaged or arrives too late to use. How do you prove conditions of the

delivery? For catalog sales, you often have receipts or some paper form of

acknowledgment of time, date, and location.

But for digital sales, such

verification may not exist or can be easily modified. These legal issues must

be resolved as we move into an age of electronic commerce.

Protecting Information

Clearly, current laws are

inadequate for protecting the information itself and for protecting

electronically based forms of commerce. So how is information to be protected

legally? As described, copyrights, patents, and trade secrets cover some, but

not all, issues related to information. Nevertheless, the legal system does not

allow free traffic in information; some mechanisms can be useful.

Criminal and Civil Law

Statutes are laws that state

explicitly that certain actions are illegal. A statute is the result of a legislative

process by which a governing body declares that the new law will be in force

after a designated time. For example, the parliament may discuss issues related

to taxing Internet transactions and pass a law about when relevant taxes must

be paid. Often, a violation of a statute will result in a criminal trial, in which the government argues for punishment

because an illegal act has harmed the desired nature of society. For example,

the government will prosecute a murder case because murder violates a law

passed by the government. In the United States, criminal transgressions are

severe, and the law requires that the judge or jury find the accused guilty

beyond reasonable doubt. For this reason, the evidence must be strong and

compelling. The goal of a criminal case is to punish the criminal, usually by

depriving him or her of rights in some way (such as putting the criminal in

prison or assessing a fine).

Civil law is a different type

of law, not requiring such a high standard of proof of guilt. In a civil case,

an individual, organization, company, or group claims it has been harmed. The

goal of a civil case is restitution: to make the victim "whole" again

by repairing the harm. For example, suppose Fred kills John. Because Fred has

broken a law against murder, the government will prosecute Fred in criminal

court for having broken the law and upsetting the order of society. Abigail,

the surviving wife, might be a witness at the criminal trial, hoping to see

Fred put in prison. But she may also sue him in civil court for wrongful death,

seeking payment to support her surviving children.

Tort Law

Special legal language

describes the wrongs treated in a civil case. The language reflects whether a

case is based on breaking a law or on violating precedents of behavior that

have evolved over time. In other words, sometimes judges may make

determinations based on what is reasonable and what has come before, rather

than on what is written in legislation. A tort

is harm not occurring from violation of a statute or from breach of a contract

but instead from being counter to the accumulated body of precedents. Thus,

statute law is written by legislators and is interpreted by the courts; tort

law is unwritten but evolves through court decisions that become precedents for

cases that follow. The basic test of a tort is what a reasonable person would

do. Fraud is a common example of tort law in which, basically, one person lies

to another, causing harm.

Computer information is

perfectly suited to tort law. The court merely has to decide what is reasonable

behavior, not whether a statute covers the activity. For example, taking

information from someone without permission and selling it to someone else as

your own is fraud. The owner of the information can sue you, even though there

may be no statute saying that information theft is illegal. That owner has been

harmed by being deprived of the revenue you received from selling the

information.

Because tort law is written

only as a series of court decisions that evolve constantly, prosecution of a

tort case can be difficult. If you are involved in a case based on tort law,

you and your lawyer are likely to try two approaches: First, you might argue

that your case is a clear violation of the norms of society, that it is not

what a fair, prudent person would do. This approach could establish a new tort.

Second, you might argue that your case is similar to one or more precedents,

perhaps drawing a parallel between a computer program and a work of art. The

judge or jury would have to decide whether the comparison was apt. In both of

these ways, law can evolve to cover new objects.

Contract Law

A third form of protection

for computer objects is contracts. A

contract is an agreement between two parties. A contract must involve three

things:

an offer

an acceptance

a consideration

One party offers something:

"I will write this computer program for you for this amount of

money." The second party can accept the offer, reject it, make a counter

offer, or simply ignore it. In reaching agreement with a contract, only an

acceptance is interesting; the rest is just the history of how agreement was

reached. A contract must include consideration of money or other valuables.

The basic idea is that two

parties exchange things of value, such as time traded for money or technical

knowledge for marketing skills. For example, "I'll wash your car if you

feed me dinner" or "Let's trade these two CDs" are offers that

define the consideration. It helps for a contract to be in writing, but it does

not need to be. A written contract can involve hundreds of pages of terms and

conditions qualifying the offer and the consideration.

One final aspect of a

contract is its freedom: the two parties have to enter into the contract

voluntarily. If I say "sign this contract or I'll break your arm,"

the contract is not valid, even if leaving your arm intact is a really

desirable consideration to you. A contract signed under duress or with

fraudulent action is not binding. A contract does not have to be fair, in the

sense of equivalent consideration for both parties, as long as both parties

freely accept the conditions.

Information is often

exchanged under contract. Contracts are ideal for protecting the transfer of

information because they can specify any conditions. "You have the right

to use but not modify this information," "you have the right to use

but not resell this information," or "you have the right to view this

information yourself but not allow others to view it" are three potential

contract conditions that could protect the commercial interests of an owner of

information.

Computer contracts typically

involve the development and use of software and computerized data. As we note

shortly, there are rules about who has the right to contract for softwareemployers

or employeesand what are reasonable expectations of software's quality.

If the terms of the contract

are fulfilled and the exchange of consideration occurs, everyone is happy.

Usually. Difficulties arise when one side thinks the terms have been fulfilled

and the other side disagrees.

As with tort law, the most

common legal remedy in contract law is money. You agreed to sell me a solid

gold necklace and I find it is made of brass. I sue you. Assuming the court

agreed with me, it might compel you to deliver a gold necklace to me, but more

frequently the court will decide I am entitled to a certain sum of money. In

the necklace case, I might argue first to get back the money I originally paid

you, and then argue for incidental damages from, for example, the doctor I had

to see when your brass necklace turned my skin green, or the embarrassment I

felt when a friend pointed to my necklace and shouted "Look at the cheap

brass necklace!" I might also argue for punitive damages to punish you and

keep you from doing such a disreputable thing again. The court will decide

which of my claims are valid and what a reasonable amount of compensation is.

Summary of Protection for Computer Artifacts

This section has presented

the highlights of law as it applies to computer hardware, software, and data.

Clearly these few pages only skim the surface; the law has countless

subtleties. Still, by now you should have a general idea of the types of

protection available for what things and how to use them. The differences between

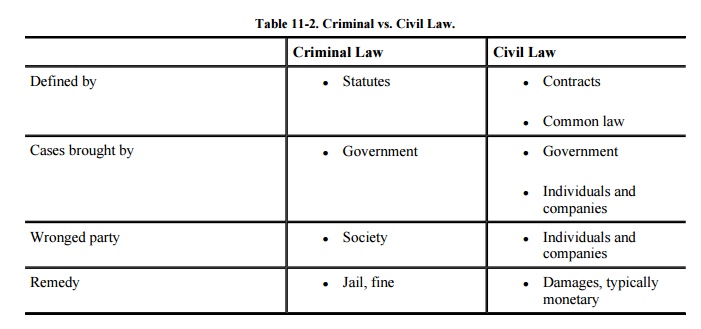

criminal and civil law are summarized in Table 11-2.

Contracts help fill the voids

among criminal, civil, and tort law. That is, in the absence of relevant

statutes, we first see common tort law develop. But people then enhance these

laws by writing contracts with the specific protections they want.

Enforcement of civil lawtorts

or contractscan be expensive because it requires one party to sue the other.

The legal system is informally weighted by money. It is attractive to sue a

wealthy party who could pay a hefty judgment. And a big company that can afford

dozens of top-quality lawyers will more likely prevail in a suit than an

average individual.

Related Topics