Chapter: Security in Computing : Legal and Ethical Issues in Computer Security

Ethical Issues in Computer Security

Ethical Issues in Computer Security

This final section helps

clarify thinking about the ethical issues involved in computer security. We

offer no answers. Rather, after listing and explaining some ethical principles,

we present several case studies to which the principles can be applied. Each

case is followed by a list of possible ethical issues involved, although the

list is not necessarily all-inclusive or conclusive. The primary purpose of

this section is to explore some of the ethical issues associated with computer

security and to show how ethics functions as a control.

Differences Between the Law and Ethics

As we noted earlier, law is

not always the appropriate way to deal with issues of human behavior. It is

difficult to define a law to preclude only the events we want it to. For

example, a law that restricts animals from public places must be refined to

permit guide dogs for the blind. Lawmakers, who are not computer professionals,

are hard pressed to think of all the exceptions when they draft a law

concerning computer affairs. Even when a law is well conceived and well

written, its enforcement may be difficult. The courts are overburdened, and

prosecuting relatively minor infractions may be excessively time consuming

relative to the benefit.

Thus, it is impossible or

impractical to develop laws to describe and enforce all forms of behavior

acceptable to society. Instead, society relies on ethics or morals to prescribe generally accepted standards of

proper behavior. (In this section the terms ethics and morals are used

interchangeably.) An ethic is an objectively defined standard of right and

wrong. Ethical standards are often idealistic principles because they focus on

one objective. In a given situation, however, several moral objectives may be

involved, so people have to determine an action that is appropriate considering

all the objectives. Even though religious groups and professional organizations

promote certain standards of ethical behavior, ultimately each person is

responsible for deciding what to do in a specific situation. Therefore, through

our choices, each of us defines a personal set of ethical practices. A set of

ethical principles is called an ethical system.

An ethic is different from a

law in several important ways. First, laws apply to everyone: One may disagree

with the intent or the meaning of a law, but that is not an excuse for

disobeying the law. Second, the courts have a regular process for determining

which law supersedes which if two laws conflict. Third, the laws and the courts

identify certain actions as right and others as wrong. From a legal standpoint,

anything that is not illegal is right. Finally, laws can be enforced to rectify

wrongs done by unlawful behavior.

By contrast, ethics are

personal: two people may have different frameworks for making moral judgments.

What one person deems perfectly justifiable, another would never consider

doing. Second, ethical positions can and often do come into conflict. As an

example, the value of a human life is very important in most ethical systems.

Most people would not cause the sacrifice of one life, but in the right context

some would approve of sacrificing one person to save another, or one to save

many others. The value of one life cannot be readily measured against the value

of others, and many ethical decisions must be founded on precisely this

ambiguity. Yet, there is no arbiter of ethical positions: when two ethical

goals collide, each person must choose which goal is dominant. Third, two

people may assess ethical values differently; no universal standard of right and

wrong exists in ethical judgments. Nor can one person simply look to what

another has done as guidance for choosing the right thing to do. Finally, there

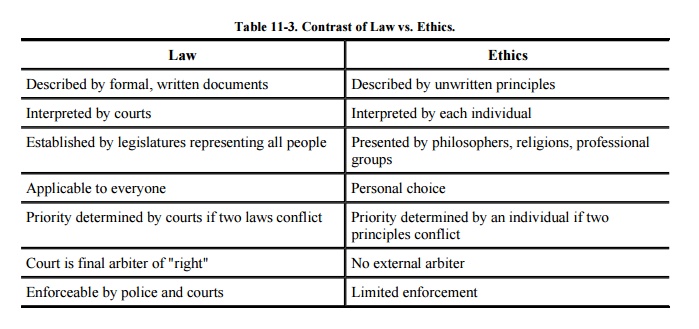

is no enforcement for ethical choices. These differences are summarized in Table 11-3.

Studying Ethics

The study of ethics is not

easy because the issues are complex. Sometimes people confuse ethics with

religion because many religions supply a framework in which to make ethical

choices. However, ethics can be studied apart from any religious connection.

Difficult choices would be easier to make if there were a set of universal

ethical principles to which everyone agreed. But the variety of social,

cultural, and religious beliefs makes the identification of such a set of

universal principles impossible. In this section we explore some of these

problems and then consider how understanding ethics can help in dealing with

issues of computer security.

Ethics and Religion

Ethics is a set of principles

or norms for justifying what is right or wrong in a given situation. To

understand what ethics is we may start by trying to understand what it is not.

Ethical principles are different from religious beliefs. Religion is based on

personal notions about the creation of the world and the existence of

controlling forces or beings. Many moral principles are embodied in the major

religions, and the basis of a personal morality is a matter of belief and

conviction, much the same as for religions. However, two people with different

religious backgrounds may develop the same ethical philosophy, while two

exponents of the same religion might reach opposite ethical conclusions in a

particular situation. Finally, we can analyze a situation from an ethical

perspective and reach ethical conclusions without appealing to any particular

religion or religious framework. Thus, it is important to distinguish ethics

from religion.

Ethical Principles Are Not Universal

Ethical values vary by

society, and from person to person within a society. For example, the concept

of privacy is important in Western cultures. But in Eastern cultures, privacy

is not desirable because people associate privacy with having something to

hide. Not only is a Westerner's desire for privacy not understood but in fact

it has a negative connotation. Therefore, the attitudes of people may be

affected by culture or background.

Also, an individual's

standards of behavior may be influenced by past events in life. A person who

grew up in a large family may place greater emphasis on personal control and

ownership of possessions than would an only child who seldom had to share.

Major events or close contact with others can also shape one's ethical

position. Despite these differences, the underlying principles of how to make

moral judgment are the same.

Although these aspects of

ethics are quite reasonable and understandable, they lead people to distrust

ethics because it is not founded on basic principles all can accept. Also,

people from a scientific or technical background expect precision and

universality.

Ethics Does Not Provide Answers

Ethical pluralism is recognizing or admitting that more than one

position may be ethically justifiableeven equally soin a given situation. Pluralism is another way of noting

that two people may legitimately disagree on issues of ethics. We expect and

accept disagreement in such areas as politics and religion.

However, in the scientific

and technical fields, people expect to find unique, unambiguous, and

unequivocal answers. In science, one answer must be correct or demonstrable in

some sense. Science has provided life with fundamental explanations. Ethics is

rejected or misunderstood by some scientists because it is "soft,"

meaning that it has no underlying framework or it does not depend on fundamental

truths.

One need only study the

history of scientific discovery to see that science itself is founded largely

on temporary truths. For many years the earth was believed to be the center of

the solar system. Ptolemy developed a complicated framework of epicycles,

orbits within orbits of the planets, to explain the inconsistency of observed

periods of rotation. Eventually his theory was superseded by the Copernican

model of planets that orbit the sun. Similarly, Einstein's relativity theory

opposed the traditional quantum basis of physics. Science is littered with

theories that have fallen from favor as we learned or observed more and as new

explanations were proposed. As each new theory is proposed, some people readily

accept the new proposal, while others cling to the old.

But the basis of science is

presumed to be "truth." A statement is expected to be provably true,

provably false, or unproven, but a statement can never be both true and false.

Scientists are uncomfortable with ethics because ethics does not provide these

clean distinctions.

Worse, there is no higher

authority of ethical truth. Two people may disagree on their opinion of the

ethics of a situation, but there is no one to whom to appeal for a final

determination of who is "right." Conflicting answers do not deter one

from considering ethical issues in computer security. Nor do they excuse us

from making and defending ethical choices.

Ethical Reasoning

Most people make ethical

judgments often, perhaps daily. (Is it better to buy from a hometown merchant

or from a nationwide chain? Should I spend time with a volunteer organization

or with my friends? Is it acceptable to release sensitive data to someone who

might not have justification for access to that data?) Because we all engage in

ethical choice, we should clarify how we do this so that we can learn to apply

the principles of ethics in professional situations, as we do in private life.

Study of ethics can yield two

positive results. First, in situations in which we already know what is right

and what is wrong, ethics should help us justify our choice. Second, if we do

not know the ethical action to take in a situation, ethics can help us identify

the issues involved so that we can make reasoned judgments.

Examining a Case for Ethical Issues

How, then, can issues of

ethical choice in computer security be approached? Here are several steps to

making and justifying an ethical choice.

Understand the situation. Learn the facts of the situation. Ask

questions of interpretation or clarification. Attempt to find out whether any

relevant forces have not been considered.

Know several theories of ethical reasoning. To make an ethical

choice, you have to know how those choices can be justified.

List the ethical principles involved. What different philosophies

could be applied in this case? Do any of these include others?

Determine which principles outweigh others. This is a subjective

evaluation. It often involves extending a principle to a logical conclusion or

determining cases in which one principle clearly supersedes another.

The most important steps are

the first and third. Too often people judge a situation on incomplete

information, a practice that leads to judgments based on prejudice, suspicion,

or misinformation. Considering all the different ethical issues raised forms

the basis for evaluating the competing interests of step four.

Examples of Ethical Principles

There are two different

schools of ethical reasoning: one based on the good that results from actions

and one based on certain prima facie duties of people.

Consequence-Based Principles

The teleological theory of

ethics focuses on the consequences of an action. The action to be chosen is

that which results in the greatest future good and the least harm. For example,

if a fellow student asks you to write a program he was assigned for a class,

you might consider the good (he will owe you a favor) against the bad (you

might get caught, causing embarrassment and possible disciplinary action, plus

your friend will not learn the techniques to be gained from writing the

program, leaving him deficient). The negative consequences clearly outweigh the

positive, so you would refuse. Teleology

is the general name applied to many theories of behavior, all of which focus on

the goal, outcome, or consequence of the action.

There are two important forms

of teleology. Egoism is the form

that says a moral judgment is based on the positive benefits to the person

taking the action. An egoist weighs the outcomes of all possible acts and

chooses the one that produces the most personal good for him or her with the

least negative consequence. The effects on other people are not relevant. For

example, an egoist trying to justify the ethics of writing shoddy computer code

when pressed for time might argue as follows. "If I complete the project

quickly, I will satisfy my manager, which will bring me a raise and other good

things. The customer is unlikely to know enough about the program to complain,

so I am not likely to be blamed. My company's reputation may be tarnished, but

that will not be tracked directly to me. Thus, I can justify writing shoddy

code."

The principle of utilitarianism is also an assessment of

good and bad results, but the reference group is the entire universe. The

utilitarian chooses that action that will bring the greatest collective good

for all people with the least possible negative for all. In this situation, the

utilitarian would assess personal good and bad, good and bad for the company,

good and bad for the customer, and, perhaps, good and bad for society at large.

For example, a developer designing software to monitor smokestack emissions

would need to assess its effects on everyone breathing. The utilitarian might

perceive greater good to everyone by taking the time to write high-quality

code, despite the negative personal consequence of displeasing management.

Rule-Based Principles

Another ethical theory is deontology, which is founded in a sense

of duty. This ethical principle states that certain things are good in and of

themselves. These things that are naturally good are good rules or acts, which

require no higher justification. Something just is good; it does not have to be

judged for its effect.

Examples (from Frankena [FRA73]) of intrinsically good things are

truth, knowledge, and true

opinion of various kinds; understanding, wisdom

just distribution of good and

evil; justice

pleasure, satisfaction;

happiness; life, consciousness

peace, security, freedom

good reputation, honor,

esteem; mutual affection, love, friendship, cooperation; morally good

dispositions or virtues

beauty, aesthetic experience

Rule-deontology is the school of ethical reasoning that

believes certain universal, self-evident, natural rules specify our proper

conduct. Certain basic moral

principles are adhered to because of our responsibilities to one another; these

principles are often stated as rights: the right to know, the right to privacy,

the right to fair compensation for work. Sir David Ross [ROS30] lists various duties incumbent on all

human beings:

fidelity, or truthfulness

reparation, the duty to

recompense for a previous wrongful act

gratitude, thankfulness for

previous services or kind acts

justice, distribution of

happiness in accordance with merit

beneficence, the obligation

to help other people or to make their lives better

nonmaleficence, not harming

others

self-improvement, to become

continually better, both in a mental sense and in a moral sense (for example,

by not committing a wrong a second time)

Another school of reasoning is

based on rules derived by each individual. Religion, teaching, experience, and

reflection lead each person to a set of personal moral principles. The answer

to an ethical question is found by weighing values in terms of what a person

believes to be right behavior.

Summary of Ethical Theories

We have seen two bases of

ethical theories, each applied in two ways. Simply stated, the two bases are

consequence based and rule based, and the applications are either individual or

universal. These theories are depicted in Table

11-4.

Related Topics