Chapter: Medical Microbiology: An Introduction to Infectious Diseases: Cryptococcus, Histoplasma, Coccidioides, and Other Systemic Fungal Pathogens

Histoplasmosis

HISTOPLASMOSIS

Histoplasmosis is limited to the endemic area, where the vast majority of cases are asymptomatic or show only a fever and cough. If affected individuals are seen by a physician, a pulmonary infiltrate and hilar adenopathy may or may not be evi-dent on a radiograph. Progressive cases show extension in the lung or enlargement of lymph nodes, liver, and spleen.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

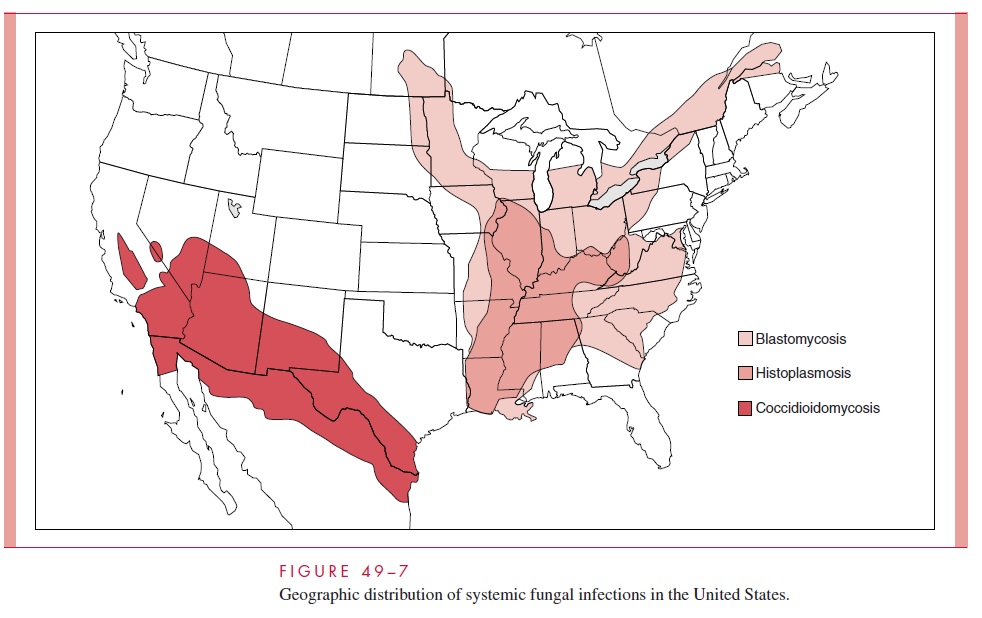

H. capsulatum grows in soil under humid climatic conditions, particularly soil containingbird or bat droppings. Inhalation of the mold microconidia, which are small enough (2 to 5μm) to reach the terminal bronchioles and alveoli, is believed to be the mode of infection. The organism has a worldwide distribution but is particularly prevalent in certain temper-ate, subtropical, and tropical zones. In the United States, the greatest concentration by far is in the areas drained by the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers (see Fig 49–7). Over 50% of the residents of states in this area show evidence of previous infection, and in some locales, up to 90% of those have positive skin tests. Disturbances of bird roosts, bat caves, and soil have been associated with point source outbreaks. Persons in endemic areas whose employment (agriculture, construction) or avocation (spelunkers) brings them in contact with these sites are at increased risk. The infection is not transmitted from person to person. Disease is more common in men but there are no racial or ethnic differences in susceptibility.

PATHOGENESIS

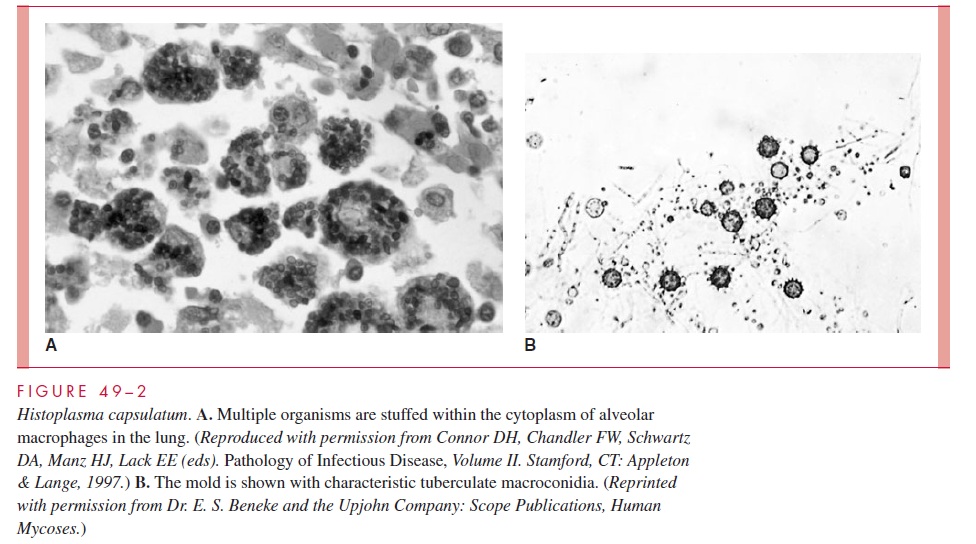

The hallmark of histoplasmosis is infection of the lymph nodes, spleen, bone marrow, and other elements of the reticuloendothelial system with intracellular growth in phagocytic macrophages. The initial infection is pulmonary, through inhalation of infectious conidia, which convert to the yeast form in the host. They attach to CD18 integrin receptors and are readily phagocytosed by macrophages and PMNs. Inside phagocytes, they continue to multiply in the cytoplasm, surviving the combined effects of the oxidative burst and phagolysosomal fusion. Key features in this survival are the ability of H. capsulatum to capture iron and calcium from the macrophage and to modulate phagolysosomal pH. The acidic pH required for optimal killing effect in the lysosome is elevated by H. capsulatum toward the neutral range (pH 6.0 to 6.5).

With continued growth, there is lymphatic spread and development of a primary lesion similar to that seen in tuberculosis . The extent of spread to the reticuloen-dothelial system within macrophages during primary infection is unknown, but such spread is presumed to occur. The vast majority of cases never advance beyond the primary stage, leaving only a calcified node as evidence of infection. Old lesions may reactivate in a small proportion of cases.

Pathologically, granulomatous inflammation with necrosis is prominent in pulmonary lesions, but H. capsulatum may be difficult to detect, even with special fungal stains. Ex-trapulmonary spread involves the reticuloendothelial system, with enlargement of the liver and spleen. Numerous organisms within macrophages may be found in these organs, in lymph nodes, or in bone marrow (see Fig 49–2A).

IMMUNITY

Infection with H. capsulatum is associated with the development of cell-mediated immunity, as demonstrated by a positive delayed hypersensitivity skin test to a mycelial antigen called histoplasmin. Infection is believed to confer long-lasting immunity, the most important component of which is CD4+ T lymphocyte mediated. In experimental infections, macrophages activated by T lymphocyte–derived cytokines are able to inhibit intracellular growth of H. capsulatum and thus control the disease. Neither B cells nor antibody have a significant influence on resistance to reinfection. Immunocompromised persons, particu-larly those with T lymphocyte–related defects, are unable to stop growth of the organism and tend to develop progressive, disseminated disease.

Related Topics