Chapter: Medical Microbiology: An Introduction to Infectious Diseases: Cryptococcus, Histoplasma, Coccidioides, and Other Systemic Fungal Pathogens

Cocci Dioido Mycosis : Clinical Aspects

COCCI DIOIDO MYCOSIS : CLINICAL ASPECTS

MANIFESTATIONS

More than one half of those infected with C. immitis suffer no symptoms, or the disease is so mild that it cannot be recalled when skin test conversion is discovered. Others develop malaise, cough, chest pain, fever, and arthralgia 1 to 3 weeks after infection. This disease, which lasts 2 to 6 weeks, is known as valley fever by the local populations in the United States. Objective findings are few. The chest x-ray is usually clear or shows only hilar adenopathy. Erythema nodosum may develop midway through the course, particularly in women. In most cases, resolution is spontaneous but only after considerable discomfort and loss of productivity. In more than 90% of cases, there are no pulmonary residua. A small number of cases progress to a chronic pulmonary form characterized by cavity formation and a slow relapsing course that extends over years. Less than 1% of all primary infections disseminate to foci outside the lung.

Disseminated disease is more common in men; in dark-skinned races, particularly Fil-ipinos; and in AIDS patients and other immunosuppressed persons. Evidence of extrapul-monary infection almost always appears in the first year after infection. The most common sites are bones, joints, skin, and meninges. Coccidioidal meningitis develops slowly with gradually increasing headache, fever, neck stiffness, and other signs of meningeal irrita-tion. The CSF findings are similar to those in tuberculosis and other fungal causes of meningitis, such as C. neoformans. Mononuclear cells predominate in the cell count, but substantial numbers of neutrophils are often present. If untreated, the disease is slowly pro-gressive and fatal.

DIAGNOSIS

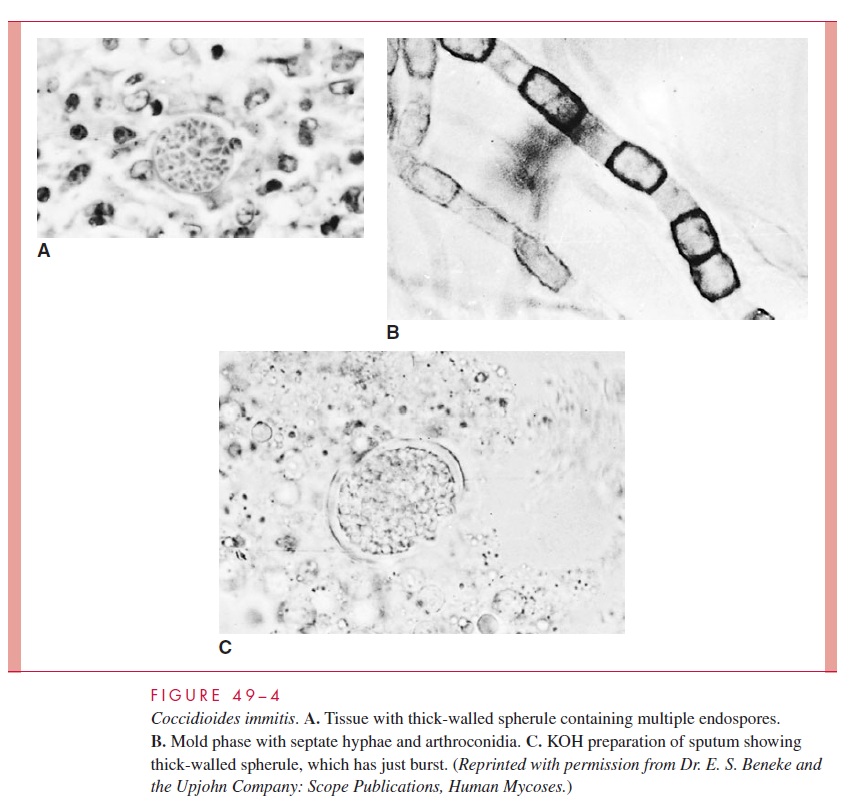

With enough persistence, direct examinations are usually rewarding. The thick-walled spherules are so large and characteristic (see Fig 49–4A and C) that they are difficult to miss in a KOH preparation or biopsy section. Skin and visceral lesions are most likely to demonstrate spherules; CSF is least likely. Spherules released into expectorated sputum are often small (10–15 mm) and immature without well-developed endospores. Spherules stain well in histologic sections with either H&E or special fungal stains.

Culture of C. immitis from sputum, visceral lesions, or skin lesions is not difficult, but must be undertaken only by those with experience and proper biohazard protection. Cultures of CSF are positive in less than half the cases of meningitis. Laboratories must be warned of the possibility of coccidioidomycosis to ensure diagnosis and avoid inadver-tent laboratory infection. The latter is particularly significant outside the endemic areas, where routine precautions may not be in place. Identification requires observation of typi-cal arthroconidia and demonstration of mycelial antigens using the exoantigen test or a gene probe.

Skin and serologic tests are particularly useful in diagnosis and management of coccidioidomycosis. The coccidioidin skin test usually becomes positive 1 to 4 weeks after the onset of symptoms of primary infection and remains so for life. Although this skin test is generally believed to be useful in clinical diagnosis and management, it is currently not commercially available. Disseminated disease is frequently associated with anergy. One half to three quarters of patients with primary infection develop serum IgM precipitating antibody in the first 3 weeks of illness. These conditions persist for 2 to 4 months. IgG antibodies detected by complement fixation tests appear somewhat later in symptomatic infections. The amount and duration depend on the extent of disease. Anti-bodies disappear with resolution and persist with continuing infection. The height of the complement fixation titer is a measure of the extent of disease. The presence of comple-ment-fixing antibody in the CSF is also important in the diagnosis of coccidioidal menin-gitis, because cultures are frequently negative. Precipitating and complement-fixing antibodies may be detected by classic methods or by more recently developed immunoas-say procedures.

TREATMENT

Primary coccidioidomycosis is self-limiting, and no antifungal therapy is indicated. Pro-gressive pulmonary disease and disseminated disease require the use of antifungal agents, usually amphotericin B. Ketoconazole has proved effective, but relapses are common. Fluconazole and itraconazole are also active against C. immitis. With the ex-ception of fluconazole, none of these agents have significant penetration into the CNS. Amphotericin B is commonly given directly into the CSF for the treatment of C. immitis meningitis.

Related Topics