Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: Anxiety Disorders: Generalized Anxiety Disorder

Generalized Anxiety Disorder: Pharmacotherapy

Pharmacotherapy

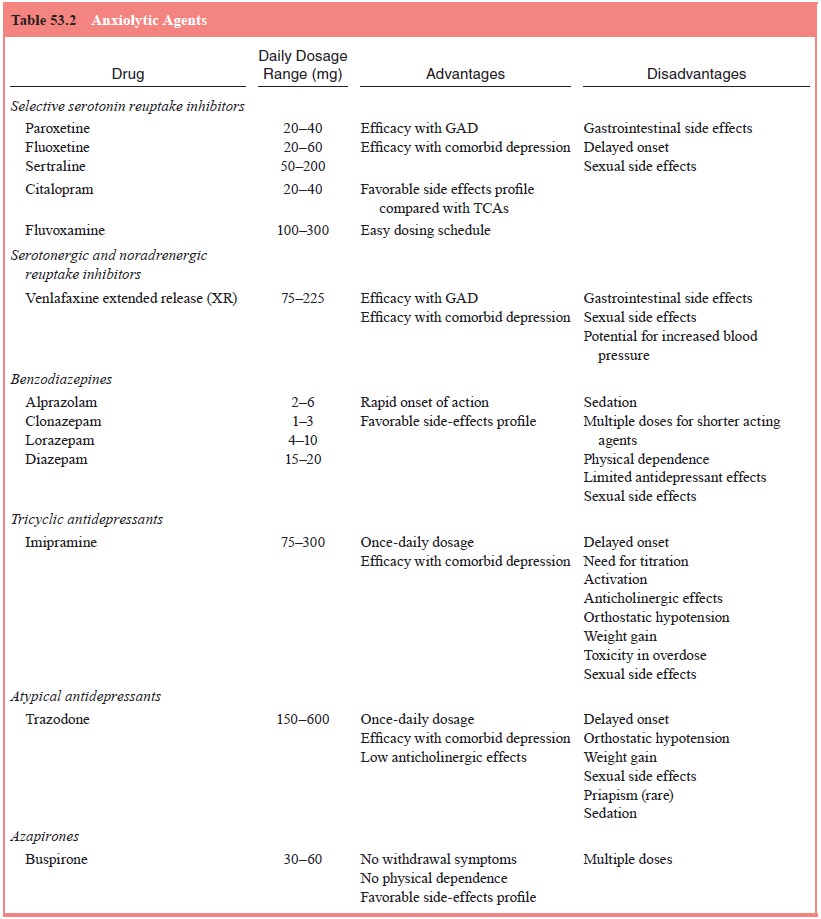

Below, we will discuss the use of various anxiolytic agents in the

treatment of GAD. Table 53.2 provides a summarization of this information.

Benzodiazepines

Benzodiazepines are commonly used for the treatment of GAD and are still

considered by some clinicians to be the first-line treatment for GAD. Several

controlled studies have demonstrated the efficacy of different benzodiazepines

such as diazepam, chlordiazepoxide and alprazolam in the treatment of GAD. The

available placebo-controlled studies found that diazepam, alpra-zolam and

lorazepam were effective in the treatment of GAD. The benzodiazepines have a

broad spectrum of effects includ-ing sedation, muscle relaxation, anxiety

reduction and decreased physiologic arousal (e.g. palpitations, tremulousness,

etc.). Inter-estingly, available studies indicate that benzodiazepines have the

most pronounced effect on hypervigilance and somatic symp-toms of GAD, but exhibited

fewer effects on psychic symptoms such as dysphoria, interpersonal sensitivity

and obsessionality (Hoehn-Saric et al.,

1988).

The main difference between individual benzodiazepines is potency and

elimination half-life. These differences may have important treatment

implications. For example, benzo-diazepines with relatively short elimination

half-lives such as alprazolam (range of 10–14 hours) may require dosing at

least three to four times a day in order to avoid interdose symptom rebound.

Conversely, the use of longer-acting compounds such as clonazepam (range of

20–50 hours) may minimize the risk of interdose symptom recurrence. In

comparative studies of differ-ent benzodiazepines, alprazolam appeared to

perform somewhat better than lorazepam. Data from the HARP study indicate that

the most frequently reported medication used by GAD patients was alprazolam

(31%), followed by clonazepam (23%) (Yonkers et al., 1996).

Benzodiazepines exert their therapeutic effects quickly, often after a

single dose. However, concern has emerged over the use of benzodiazepines,

particularly long-term benzodiazepine use. Side effects of benzodiazepines,

such as sedation, psycho-motor impairment and memory disruption, were noted by

treating clinicians, and confirmed in research studies. Further, although it

was suggested that the use pattern of benzodiazepines by pa-tients with anxiety

disorders may not represent abuse, addiction, or drug dependence as typically

understood, the chronic use of benzodiazepines in the treatment of GAD has been

increasingly discouraged in recent years.

When initiating treatment with benzodiazepines, it is helpful for patients

to take an initial dose at home in the evening to see how it affects them.

Gradual titration to an effective dose allows for limiting unwanted adverse

effects. A final daily dos-age of alprazolam between 2 and 4 mg/day, 1 and 2

mg/day for clonazepam, or 15 and 20 mg/day of diazepam is usually suf-ficient

for the majority of patients. Upon treatment discontinu-ation, it is important

to consider appropriate taper in order to avoid withdrawal symptoms. Possible

factors that may contrib-ute to the severity of withdrawal and the ultimate

outcome of benzodiazepine taper include the dosage, duration of treatment, the

benzodiazepine elimination half-life and potency, and the rate of

benzodiazepine taper (gradual versus abrupt). Addition-ally, patient factors such

as premorbid personality features have been implicated. It appears that a taper

rate of 25% per week is probably too rapid for many patients. We, therefore,

recommend a slow benzodiazepine taper of at least 4 to 8 weeks, with the final

50% of the taper conducted even more gradually, with the patient decreasing by

the lowest possible daily dose of the ben-zodiazepines during this period. We

also recommend continu-ing to use divided doses of short to intermediate

half-life ben-zodiazepines (alprazolam, lorazepam) during taper to minimize

fluctuations in benzodiazepine levels over a 24-hour period, or using longer

half-life benzodiazepines (such as clonazepam) which have the advantage of

maintaining a once- or twice-daily dosing schedule.

Tricyclic Antidepressants

Clinical trials conducted in the early 1990s have confirmed that tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) may also be effective in the treatment of GAD. These studies, as well as other trials, suggest that TCAs may be especially effective in the treatment of psychic symptoms of GAD (Brawman-Mintzer and Lydiard, 1994).The relationship between plasma levels of TCAs and their anxiolytic efficacy in patients with GAD has not been studied. Until this relationship is clarified, decisions regarding the total daily doses and the monitoring of plasma levels should be based on the patient’s treatment response and side-effects profile. Fur-ther, due to potential jitteriness, restlessness and agitation during the initial stages of treatment, we suggest that the ini-tial dose of the TCAs in patients with GAD may need to be low (for example 10 mg/day of imipramine), and increased gradually.

Adverse effects commonly associated with the use of TCAs include

anticholinergic effects (dry mouth, blurred vision, constipation),

cardiovascular effects (orthostatic hypotension, slightly increased heart

rate), sexual side effects and weight gain. As mentioned, patients may also

experience significant jitteriness, restlessness and agitation during the

initial stages of treatment. These side-effects often limit the acceptability

of TCAs by many patients. Potential toxicity in overdose has been of concern to

clinicians as well. Due, in part, to the side-effect profile, need for dose

titration and importantly the emergence of new and effective agents (as

described below), the use of TCAs in the treatment of GAD has been reserved for

those resistant to these newer agents.

Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are rapidly be-coming a

key tool in the treatment of GAD. SSRIs are generally well tolerated. The most

problematic side effect associated with SSRI use is interference with sexual

function (e.g., delayed or-gasm or abnormal ejaculation) in women and men. A

variety of treatment strategies have been suggested for the management of

SSRI-induced sexual dysfunction. Such strategies include wait-ing for tolerance

to develop, dosage reduction, drug holidays and various augmentation strategies

with 5-hydroxytryptamine-2 (5-HT2), 5-HT3 and alpha-2-adrenergic receptor antagonists, 5-HT1A and dopamine receptor agonists,

and phosphodiesterase (PDE5) enzyme inhibitors.

Serotonergic and Noradrenergic Reuptake Inhibitors

The antidepressant venlafaxine extended release (XR) is an in-hibitor of

both 5-HT and NE reuptake (SNRI). Several large, placebo-controlled trials have

evaluated it in the treatment of patients with DSM-IV-diagnosed GAD. As a

result, venlafaxine XR was the first antidepressant approved by the FDA for the

treat-ment of GAD. Results from two short-term studies indicate that

venlafaxine XR (75, 150 and 225 mg/day) was significantly more effective than

placebo and superior to buspirone on certain anxi-ety measures and in the

prevention of relapse (Sheehan, 2001). The adverse events for GAD patients

treated with venlafaxine XR resembled those in depression trials. The most

common ad-verse events included nausea, somnolence, dry mouth, dizziness,

sweating, constipation and anorexia.

Other Antidepressants

Both trazodone and imipramine have comparable efficacy to di-azepam. In

addition, trazodone and imipramine exhibit higher efficacy in the treatment of

psychic symptoms such as tension, apprehension and worry. The

alpha-2-adrenoreceptor antagonist mitrazapine, which is also a 5-HT2, 5-HT3 and H(1) receptors an-tagonist,

has been evaluated as a potential anxiolytic in the treat-ment of patients with

major depressive disorder and comorbid GAD in an 8-week, open-label study

(Goodnick et al., 1999). Re-sults

suggest that this antidepressant may be useful in the treat-ment of anxiety

symptoms.

Azapirones

Buspirone hydrochloride, the only currently marketed aza-pirone, was the

first nonbenzodiazepine anxiolytic agent ap-proved for the treatment of

persistent anxiety by FDA. Re-sults have been mixed about the efficacy of

buspirone over placebo. For example, in four placebo-controlled studies that

compared buspirone with a standard benzodiazepine, two showed no benefit for

diazepam and buspirone over placebo, and two showed no benefit for buspirone

over placebo. Benzo-diazepines may also be slightly more effective than

buspirone in the treatment of somatic symptoms of anxiety but no signif-icant

differences appear to exist between buspirone and ben-zodiazepines in measures

of psychic anxiety (Rickels et al.,

1997). Side effects most frequently associated with buspirone use included

gastrointestinal system-related side effects, such as appetite disturbances and

abdominal complaints, and diz-ziness. Prior use of benzodiazepines may

adversely affect the therapeutic response to buspirone. DeMartinis and

colleagues (2000) found that buspirone treatment was less effective for

patients who had been taking benzodiazepines within 30 days of initiating

buspirone treatment. Delle Chiaie and colleagues (1995) reported that a gradual

2-week taper of lorazepam with a simultaneous addition of buspirone for 6 weeks

prevents the development of clinically significant rebound anxiety or

benzodiazepine withdrawal. This approach was shown to pro-vide clinically

significant relief of anxiety symptoms in GAD patients previously treated with

benzodiazepines for 8 to 14 weeks.

Perhaps the most significant problem with the use of buspirone has been

that experts have advocated too low a dose to produce symptom reduction. In

order to achieve optimal re-sponse, buspirone dosing in the range of at least

30 to 60 mg/day is currently recommended.

Other Agents

Hydroxyzine is a histamine-1 receptor blocker and a muscarinic receptor

blocker. Recent controlled trials with the antihistamine have suggested that

this compound may be effective in the acute treatment of GAD symptoms. Finally,

the potential use of the an-ticonvulsant gabapentin in the treatment of anxiety

symptoms has also been suggested.

Related Topics