Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: Anxiety Disorders: Generalized Anxiety Disorder

Generalized Anxiety Disorder: Differential Diagnosis

Differential Diagnosis

Psychiatric Conditions

GAD and other psychiatric disorders such as major depressive disorder,

often creates diagnostic and treatment dilemmas for the clinician and may

complicate the difficult task of differential di-agnosis and treatment

planning. This section will highlight the major disorders that should be

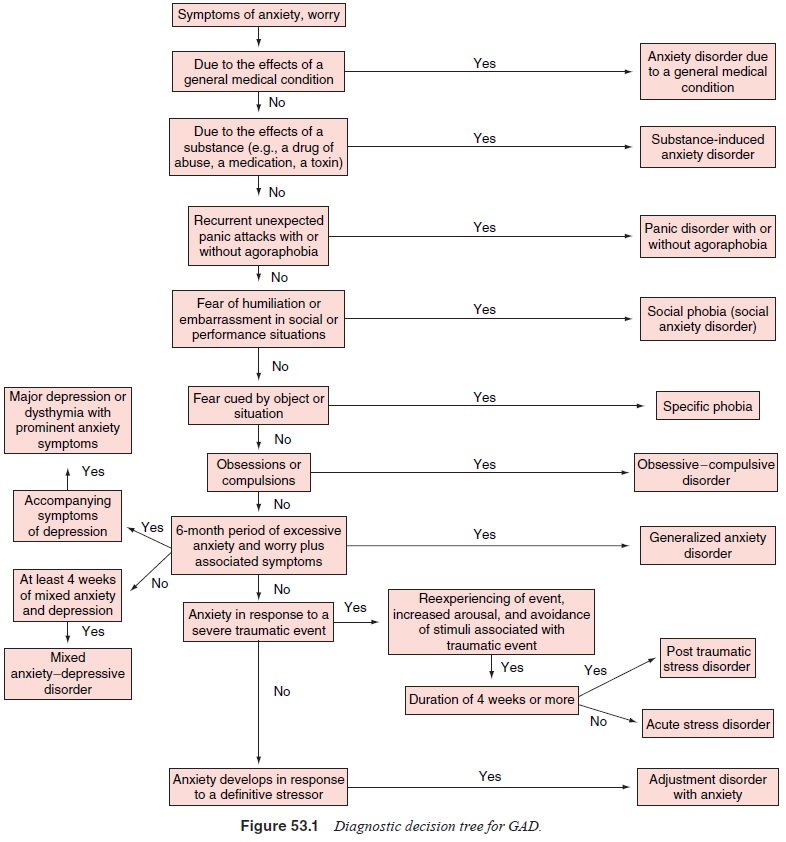

considered in the differential di-agnosis of GAD (Figure 53.1).

Major Depressive Disorder and Dysthymic Disorder

Several symptom profiles discriminate between major depres-sive disorder

or dysthymic disorder and GAD. Patients with ma-jor depressive disorder exhibit

higher rates of dysphoric mood, psychomotor retardation, suicidal ideation,

guilt, hopelessness and helplessness, as well as more work impairment than

patients with GAD. In contrast, patients with GAD show higher rates of somatic

symptoms, specifically, muscle tension and autonomic symptoms (e.g.,

respiratory or cardiac complaints) than depressed patients.

Panic Disorder With/Without Agoraphobia

Some researchers have suggested that GAD is attributable to panic disorder.

However, clear differences exist between GAD and panic disorder. For example,

panic disorder is characterized by the presence of panic attacks; that is,

recurrent, discrete epi-sodes of intense anxiety or fear associated with a

cluster of so-matic symptoms reflecting autonomic hyperactivity such as rapid

heartbeat, dizziness, numbness or tingling, trouble breathing or choking, and

nausea or vomiting. In contrast, patients with GAD experience predominantly

symptoms of muscle tension and vigi-lance such as fatigue, muscle soreness,

insomnia, difficulty con-centrating, restlessness and irritability. Patients

with panic disor-der tend to seek treatment earlier in life than patients with

GAD. Additionally, reports of types of worry differ between those diagnosed

with GAD and those with panic disorder. For exam-ple, panic patients worry

about having additional panic attacks, whereas GAD patients worry

unrealistically about a number of everyday issues.

Obsessive–Compulsive Disorder

Anxiety is part of the clinical picture of obsessive–compulsive disorder

(OCD) and may be a central factor in initiating and main-taining obsessions and

compulsions. Interestingly there are also some data suggesting that OCD and GAD

may be related. For ex-ample, Black and associates (1992) found an increased

prevalence of GAD among relatives of patients with OCD. However, several

features distinguish the excessive worry that accompanies GAD from the

obsessional thoughts of OCD. Obsessive thoughts are described as ego-dystonic intrusions

that often take the form of urges, impulses, or images. They are often

senseless and are fre-quently accompanied by time-consuming compulsions

designed to reduce mounting anxiety. In contrast, the worries in GAD are about

realistic concerns, such as health and finances.

Other Anxiety Disorders

In phobic disorders, the anxiety is characteristically associ-ated with

a specific phobic object or situation that is frequently avoided by the

patient. Such is the case with social anxiety dis-order as well, in which the

individual is afraid of or avoids situ-ations in which he or she may be the

focus of potential scrutiny by others. Anxiety is also a characteristic part of

the presentation of post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and acute stress

disor-der. However, unlike in GAD, the principal symptoms experi-enced in PTSD

and acute stress disorder follow exposure to a traumatic event and are

characterized by avoidance of reminders of the event and persistent

reexperiencing of the traumatic event. In addition, in contrast to GAD which

must last at least 6 months, acute stress disorder does not persist for more

than 4 weeks. Finally, in adjustment disorders anxiety when present occurs in

response to a specific life stressor or stressors and generally does not

persist for more than 6 months (American Psychiatric Association, 1994).

Normal Anxiety

Worry and anxiety are part of normal human behavior, and it may be

difficult to define a cutoff point distinguishing normal or trait anxiety

(i.e., a relatively stable tendency to perceive various situations as

threatening) from GAD. However, in-dividuals suffering from a “disorder”

exhibit significant dis-tress and impairment in functioning as a result of

their anxiety symptoms.

Anxiety Disorder due to a General Medical Condition

Many general medical conditions may present with prominent anxiety

symptoms. If not identified and properly addressed, these conditions may

adversely affect the treatment outcome of the anxious patient. In this section

we will highlight important medical conditions in the differential diagnosis of

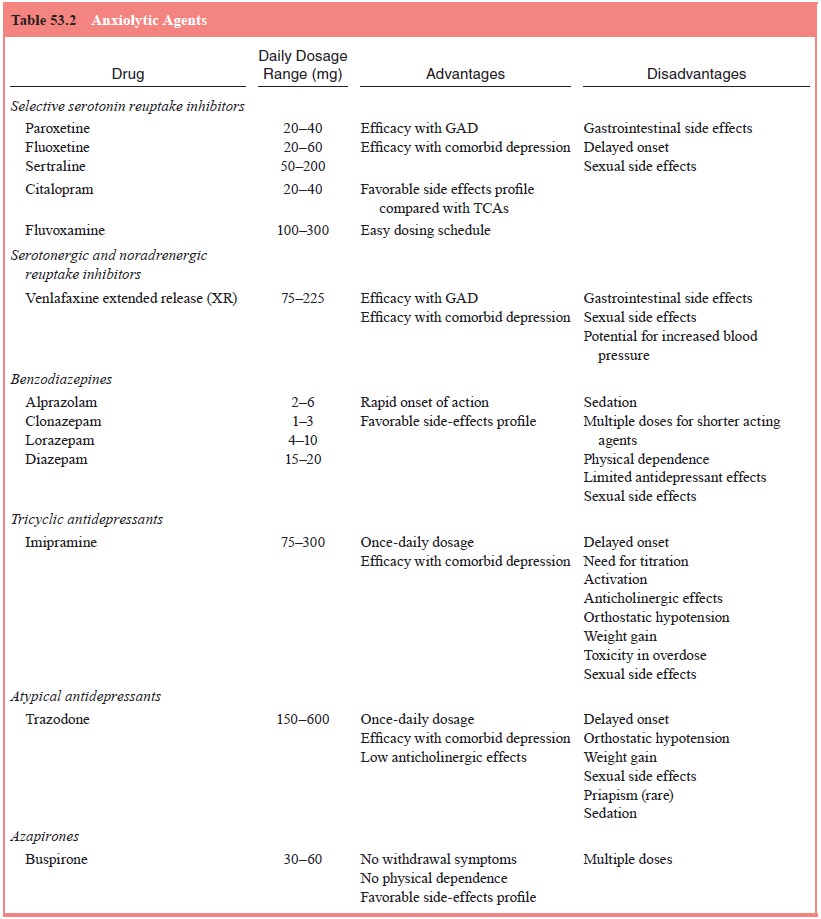

generalized anxiety (see Table 53.2).

Cardiovascular Disorders

Patients with GAD may complain of palpitations, skipped heart-beats and

chest pain. In addition, many GAD patients, espe-cially males, fear having an

acute myocardial infarction and often present to the emergency room for

evaluation. However, most patients with GAD without a concomitant

cardiovascular disease do not experience severe chest pain. Following the

con-troversial evidence suggesting an association between mitral valve prolapse

(MVP) and panic disorder, researchers evalu-ated the prevalence of MVP in

patients with GAD and found no evidence of increased prevalence in patients

with GAD. Nevertheless, patients with anxiety symptoms associated with

unexplained chest pain should be evaluated for possible cardio-vascular

disease.

Hyperthyroidism

Anxiety

is a prominent feature of hyperthyroidism with some overlap in the

symptomatology of thyrotoxicosis and GAD. Symp-toms such as tachycardia,

tremulousness, irritability, weakness and fatigue are common to both disorders.

In GAD, however, the peripheral manifestations of excessive concentrations of

circulat-ing thyroid hormones are absent, including symptoms such as weight

loss, increased appetite, warm and moist skin, heat intol-erance and dyspnea on

effort. Presence of goiter makes the diag-nosis of hyperthyroidism likely;

however, the absence of thyroid enlargement does not exclude it. Thus,

confirmatory laboratory tests (free T4, T3 and TSH) assume significant diagnostic impor-tance. In mild cases,

laboratory tests may be within the upper limit of the normal range, in which

case a thyroid releasing hor-mone stimulation test is indicated.

Pheochromocytomas

Pheochromocytomas, also known as chromaffin tumors, pro-duce, store and

secrete catecholamines. They are derived most often from the adrenal medulla,

as well as the sympathetic ganglia and occasionally from other sites. The

clinical fea-tures of these tumors, most commonly hypertension and

hy-pertensive paroxysms, are predominantly due to the release of

catecholamines. Patients may also experience diaphoresis, tachycardia, chest

pain, flushing, nausea and vomiting, head-ache and significant apprehension.

Although the clinical pres-entation frequently mimics spontaneous panic

attacks, pheo-chromocytomas should also be considered in the differential

diagnosis of GAD. The diagnosis of pheochromocytoma can be confirmed by

increased levels of catecholamines (epine-phrine and norepinephrine) or

catecholamine metabolites (metanephrines and vanillylmandelic acid) in a

24-hour urine collection.

Other Medical Conditions

Menopause is commonly referred to as the period that encom-passes the

transition between the reproductive years and beyond the last episode of

menstrual bleeding. Frequently associated with significant anxiety, menopause

should be considered in the differential diagnosis of GAD. However, other

associated symptoms such as vasomotor instability, atrophy of urogenital epithelium

and skin, and osteoporosis make the diagnosis of menopause probable. Another

endocrinologic disorder, hyper-parathyroidism, can present with anxiety

symptoms, and the ini-tial evaluation of serum calcium levels may be indicated.

Finally, certain neurologic conditions such as complex partial seizures,

intracranial tumors and strokes, and cerebral ischemic attacks may be

associated with symptoms typically observed in anxiety disorders and may

require appropriate evaluation.

Substance-induced Anxiety Disorder

Anxiety disorders can occur frequently in association with in-toxication

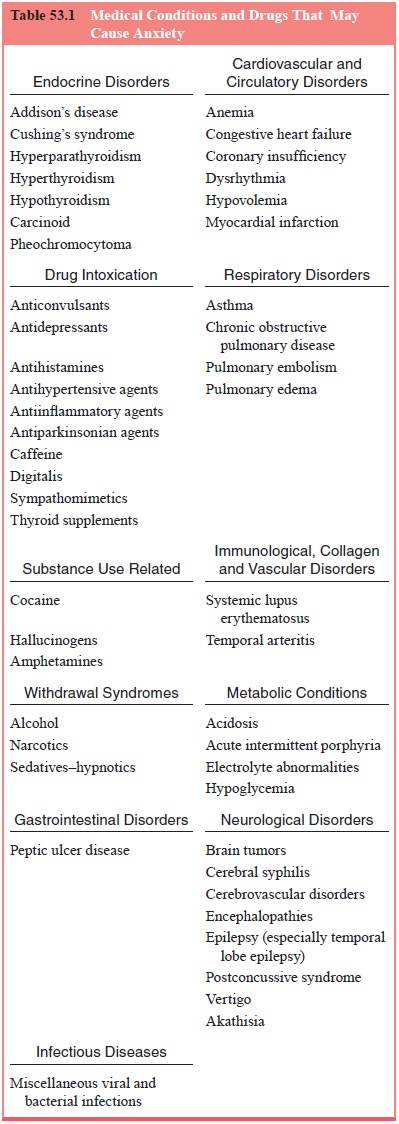

and withdrawal from several classes of substances (see Table 53.1). Excessive

use of caffeine, especially in children and adolescents, may cause significant

anxiety. Cocaine intoxi-cation may be associated with anxiety, agitation and

hypervigi-lance. During cocaine withdrawal, patients may also present with

prominent anxiety, irritability, insomnia, fatigue, depression and cocaine

craving. Adverse reaction to marijuana includes extreme anxiety that usually

lasts less than 24 hours. Mild opioid with-drawal presents with symptoms of

anxiety and dysphoria. How-ever, accompanying symptoms such as elevated blood

pressure, tachycardia, pupilary dilatation, rhinorrhea, piloerection and lac-rimation

are rare in patients with GAD.

The clinical phenomenology observed both in alcohol and

sedative–hypnotic drug withdrawal and in GAD, although variable, may be highly

similar. In both conditions, nervousness, tachycardia, tremulousness, sweating,

nausea and hyperventila-tion occur prominently. Additionally, the same drugs

(i.e., ben-zodiazepines) can be used to treat anxiety symptoms, and some

patients may use alcohol in an attempt to alleviate anxiety. Thus, the symptoms

of an underlying anxiety disorder may be difficult to differentiate from the

withdrawal symptoms associated with the use of benzodiazepines or alcohol.

The use

of many commonly prescribed medications may produce side effects manifesting as

anxiety (see Table 53.1). Such medications include sympathomimetics or other

bronchodilators such as theophilline, anticholinergics, antiparkinsonian

prepara-tions, corticosteroids, thyroid supplements, oral contraceptives, The

use of many commonly prescribed medications may produce side effects

manifesting as anxiety (see Table 53.1). Such medications include

sympathomimetics or other bronchodilators such as theophilline,

anticholinergics, antiparkinsonian prepara-tions, corticosteroids, thyroid

supplements, oral contraceptives,

Related Topics