Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: Anxiety Disorders: Generalized Anxiety Disorder

Generalized Anxiety Disorder: Course, Treatment, Doctor-Patient Relationship

Course

Retrospective and prospective reports indicate that the typical course

of GAD is chronic, nonremitting, and that it often per-sists for a decade or

longer. Rickels and colleagues (1986) re-ported that two-thirds of patients

treated initially with diazepam relapsed within 1 year of discontinuation of

treatment. Other studies utilizing criteria prior to the DSM-III-R for GAD

found comparable levels of chronicity, with almost half the patients re-porting

moderate symptoms at follow-up (Yonkers et

al., 2000).

HARP, a prospective, naturalistic study of 711 adults with DSM-III-R anxiety disorders, recruited initially from psychiat-ric clinics and hospitals in the Boston Metropolitan area, indi-cated that only 15% of those with GAD at baseline experienced a full remission for 2 months or longer at any time during the first year after baseline, and only 25% had a full remission in the 2 years after baseline (Yonkers et al., 1996). Further, among patients who experienced full or partial remission, 27 and 39% respectively, experienced a full relapse during a 3-year follow-up period (Yonkers et al., 2000). Chronicity of GAD was also asso-ciated with cluster B and C personality disorders or a concurrent Axis I comorbidity. Wittchen and coworkers (1994) found that approximately 80% of subjects with GAD reported substantial interference with their life, a high degree of professional help-seeking, and a high prevalence of taking medications because of their GAD symptoms. The disability associated with GAD was found to be similar to that found in individuals with panic disor-der or major depression.

Treatment Approaches

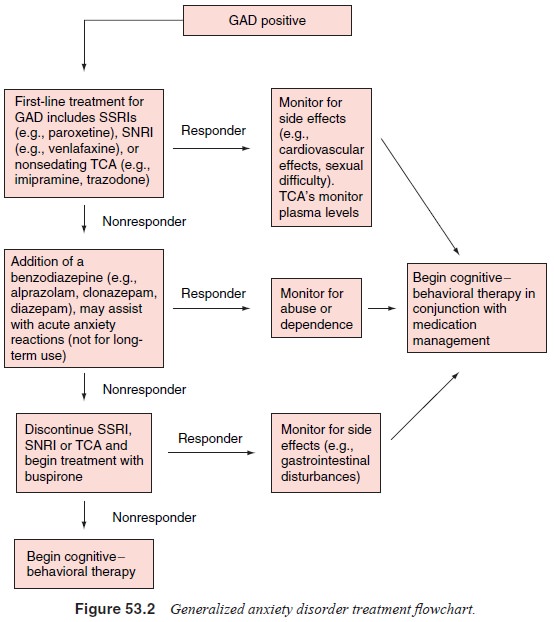

GAD is a chronic, relapsing illness, which means that most treat-ments

do not cure the patient. Furthermore, it also suggests that when treatments are

discontinued, symptoms may return. It fol-lows that a thorough understanding of

the long-term benefits and risks associated with the different treatments

available is impor-tant. Thus, each case must be considered individually

accord-ing to the severity and chronicity of the disorder, the severity of

somatic symptoms, the presence of stressors, and the presence of specific

personality traits. The clinician may also need to work with the patient to

determine how much improvement is suffi-cient. For example, a reduction in

disability may occur without a marked change in symptoms. Symptoms may persist

but oc-cur less frequently, or their intensity may be reduced. All these

variations have important treatment implications, including deci-sions regarding

the need for long-term treatment. Patients with milder forms of GAD may respond

well to simple psychologi-cal interventions, and require no medication

treatment. In more severe forms of GAD, it may become necessary to see the

pa-tient regularly and to provide both more specific psychological and

pharmacological interventions. Figure 53.2 can be used as a guide to the

treatment of GAD.

During the early (acute) phase of treatment, an attempt should be made

to control the patient’s symptomatology. It may take 3 to 6 months for an

optimal response to be achieved. How-ever, there may be a considerable

variation in the length of the initial treatment phase. For example, clinical

response to ben-zodiazepines occurs early in treatment. Response to other

anxi-olytic medications or to cognitive–behavioral treatment gener-ally

requires longer periods of time. During the maintenance phase, treatment gains

are consolidated. Unfortunately, studies suggesting how long treatment should

be continued are limited. Routinely, pharmacological treatment is continued for

a total of 6 to 12 months before attempting to discontinue medications. Recent

data indicate that “maintenance” psychotherapeutic treat-ments such as

cognitive–behavioral therapy may be helpful in maintaining treatment gains in

patients with anxiety disorders following the discontinuation of

pharmacotherapy. It is clear that many patients may experience chronic and

continuous symptoms that require years of long-term treatment.

Doctor–Patient Relationship

The vast majority of patients with GAD who present for treat-ment have

been ill for many years and frequently have received a variety of treatments.

Some patients have been sent to psychia-trists for treatment as a “last resort”

in order to learn how to cope with their various ill-defined somatic and

emotional complaints. Patients may feel shame and guilt over their inability to

control symptoms. They are often demoralized and angry, and feel that their

symptoms are not taken seriously. Thus, it is important to help the patient

understand their illness and to conceptualize it as a health problem rather

than a “personal weakness”. Once the burden of perceived responsibility is

lifted from the patient, and they believe that effective treatment of their

illness is possible, a working alliance with the treating physician can begin.

The treatment plan should be outlined clearly, and the patient cau-tioned that

recovery may have a gradual, variable course. Finally, during the critical

early stages of treatment, the clinician should make a special effort to be

available in person or by phone to answer questions and provide support.

Related Topics