Chapter: Modern Pharmacology with Clinical Applications: Gene Therapy

Gene Therapy

Gene

Therapy

Most drugs used today are

designed to treat symp-toms rather than cure the underlying disease. Notable

exceptions include cytotoxic chemotherapeutic agents and agents that restore or

modulate hormone function. However, increased understanding of the molecular

and genetic etiology of diseases may permit permanent modification of organ

function by drug-oriented meth-ods. The first disease-associated gene, -globin,

was cloned over 25 years ago. It is now theoretically possible to isolate,

sequence, and analyze genes causally associ-ated with many heritable and

acquired human diseases, including cystic fibrosis, Duchenne’s muscular

dystro-phy, and Gaucher’s disease. Moreover, with the com-plete sequencing of

the human genome, many of the es-timated 100,000 human genes may become

candidates for genetic manipulations. Thus, it is now possible to propose

molecular pharmacological and genetic ap-proaches to therapy . Many of these

approaches fall un-der the general rubric of gene therapy.

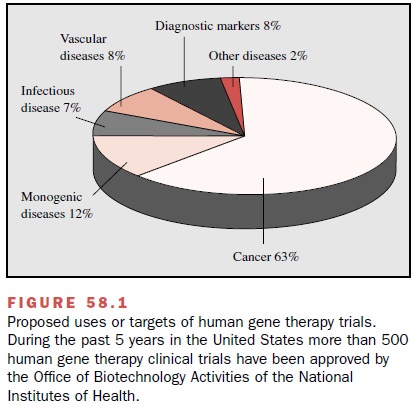

Germ cell gene therapy will

require considerable dis-cussion about ethical issues and extensive information

before it can be applied to humans, but somatic cell gene therapy in humans is

now being extensively explored. During the past 5 years in the United States

alone, more than 500 human gene therapy clinical trials aimed at treating

conditions ranging from inherited disorders such as cystic fibrosis to cancer

and AIDS, have been ap-proved by the Office of Biotechnology Activities (OBA,

formerly the Recombinant DNA Advisory Committee) of the National Institutes of

Health. Nearly 3500 patients have been enrolled in these studies (Fig. 58.1).

With few exceptions, gene

therapy was considered safe if not particularly effective until the death of an

18-year-old man in 1999, the first fatal outcome for a pa- tient in a phase I

gene therapy protocol. This death has stimulated a substantial review of the

oversight mecha-nisms in human gene transfer research. One of the first

successes of gene therapy was reported in 2000, when three infants with a fatal

form of severe combined im-munodeficiency syndrome (SCID) received ex vivo gene

therapy with a recombinant mouse leukemia viral vector encoding the γC receptor gene. After 10

months, γC transgene expression in T- and NK cells was de-tected and T-, B-,

and NK-cell counts and function were comparable to those of age-matched

controls.

Although numerous obstacles

must be overcome before gene therapy will be routinely employed, a rig-orous

approach to investigating the safety and efficacy of gene transfer will ensure

that clinical strategies em-ploying genetic manipulation are rationally

incorpo-rated into the therapeutic armamentarium.

Related Topics