Chapter: Medical Physiology: Pulmonary Circulation, Pulmonary Edema, Pleural Fluid

Fluid in the Pleural Cavity

Fluid in the Pleural Cavity

When the lungs expand and contract during normal breathing, they slide back and forth within the pleural cavity. To facilitate this, a thin layer of mucoid fluid lies between the parietal and visceral pleurae.

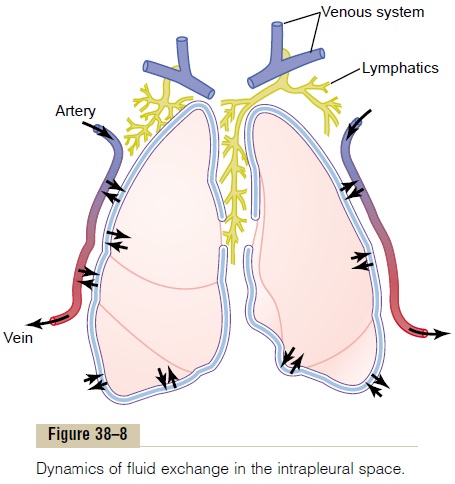

Figure 38–8 shows the dynamics of fluid exchange in the pleural space. The pleural membrane is a porous, mesenchymal, serous membrane through which small amounts of interstitial fluid transude continually into the pleural space. These fluids carry with them tissue proteins, giving the pleural fluid a mucoid characteris-tic, which is what allows extremely easy slippage of the moving lungs.

The total amount of fluid in each pleural cavity is nor-mally slight, only a few milliliters. Whenever the quan-tity becomes more than barely enough to begin flowing in the pleural cavity, the excess fluid is pumped away by lymphatic vessels opening directly from the pleural cavity into (1) the mediastinum, (2) the superior surface of the diaphragm, and (3) the lateral surfaces of the parietal pleura. Therefore, the pleural space—the space between the parietal and visceral pleurae—is called a potential space because it normally is so narrow that itis not obviously a physical space.

“Negative Pressure” in Pleural Fluid. A negative force isalways required on the outside of the lungs to keep the lungs expanded. This is provided by negative pressure in the normal pleural space. The basic cause of this neg-ative pressure is pumping of fluid from the space by the lymphatics (which is also the basis of the negative pres-sure found in most tissue spaces of the body). Because the normal collapse tendency of the lungs is about –4 mm Hg, the pleural fluid pressure must always be at least as negative as –4 mm Hg to keep the lungs expanded.

Actual measurements have shown that the pressure is usually about –7 mm Hg, which is a few mil-limeters of mercury more negative than the collapse pressure of the lungs. Thus, the negativity of the pleural fluid keeps the normal lungs pulled against the parietal pleura of the chest cavity, except for an extremely thin layer of mucoid fluid that acts as a lubricant.

Pleural Effusion. Pleural effusion means the collection oflarge amounts of free fluid in the pleural space.The effu-sion is analogous to edema fluid in the tissues and can be called “edema of the pleural cavity.” The causes of the effusion are the same as the causes of edema in other tissues, including (1) blockage of lymphatic drainage from the pleural cavity; (2) cardiac failure, which causes excessively high periph-eral and pulmonary capillary pressures, leading to excessive transudation of fluid into the pleural cavity;(3) greatly reduced plasma colloid osmotic pressure, thus allowing excessive transudation of fluid; and (4) infection or any other cause of inflammation of the sur-faces of the pleural cavity, which breaks down the cap-illary membranes and allows rapid dumping of both plasma proteins and fluid into the cavity.

Related Topics