Chapter: XML and Web Services : Applied XML : Applied XML in Vertical Industry

Finance and Accounting: The Extensible Business Reporting Language (XBRL)

Finance and Accounting

The finance industries of banking, accounting, securities trading,

research and reporting, and economics have always needed timely, accurate, and

critical access to information. As such, they have always been early

implementers of electronic document exchanges. Automatic Teller Machines (ATMs)

have implemented early forms of electronic com-merce since the late 1970s.

However, XML now allows for lower cost of delivery for this information;

therefore, both existing and new standards are being created for the delivery

of financial-related information. Of course, in this particular industry,

security and time-sensitiveness are the key issues that XML standards must

resolve.

The Extensible Business Reporting Language (XBRL)

One of the most important financial activities within a corporation is

the reporting of financial or business data. Reporting of financial data

happens throughout a business organization and even external to it. Business

units, divisions, entire corporations, sub-sidiaries, partners, regulatory

agencies, and the government all require financial reports of one sort or

another. The strong need for this sort of business reporting is met with an

equally strong challenge in the difficulty to share financial data across

disparate systems. Typically, many systems in an organization store financial

and related business informa-tion—accounting systems, supply-chain systems,

Customer Relationship Management (CRM), sales and marketing, Enterprise

Resource Planning (ERP), asset and inventory management, and human resources

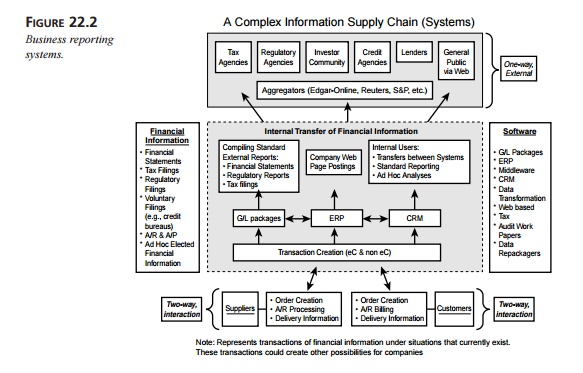

systems are just a few such repositories of financial and business data. Figure

22.2 illustrates the complex universe of financial reporting sys-tems and

interactions. The challenge is therefore great to have all these systems

transmit their data in a common format that can then be aggregated for the

purpose of creating consolidated balance sheets, reports of income, financial

statements, financial informa-tion, nonfinancial information, regulatory

filings, such as annual and quarterly financial statements, and other data

necessary for the daily operation of the business and compli-ance with

regulations.

The Extensible Business Reporting Language (XBRL) solves this problem by

providing software vendors, programmers, and end users who adopt it a means to

enhance the cre-ation, exchange, and comparison of business reporting

information. The primary users of the XBRL specification are those responsible

for the preparation of financial informa-tion, intermediaries in those

preparation and distribution processes, end users of business report

information, as well as vendors who supply software and services to the

previous user types. The overall intention is to balance the needs of these

groups, creating a prod-uct that provides benefits to all groups. Although XBRL

represents a new methodology for data information exchange, its goal is to

facilitate current business reporting practice, not to change or set new

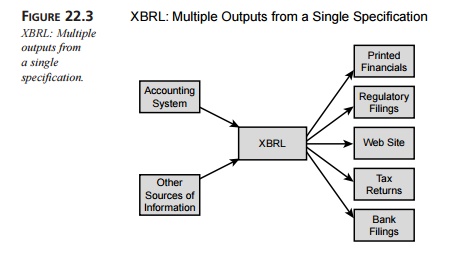

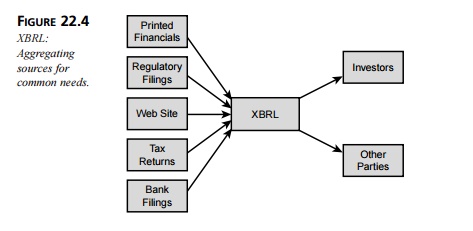

accounting standards. The general goals of the format can be seen in Figure

22.3 and Figure 22.4.

XBRL provides users with a standard format in which to prepare,

exchange, extract, and compare financial reports that can be subsequently

presented in a variety of ways. The specification also facilitates the ability

to “drill down” to detailed information, authorita-tive literature, audit

information, and accounting working papers. XBRL instance docu-ments transmit a

set of financial facts. There is no constraint on how much or how little

information these documents can contain. For example, an XBRL document can

contain just a single item of financial information, such as what the cost of

goods sold was for last quarter.

XBRL is not a single standard but rather a suite of many related

standards. The specifica-tion is composed of a global specification that

contains “taxonomies” or dependent stan-dards that meet the requirements of

specific user communities. The reason for this structure is quite necessary. In

part, the reasons are geographic and political: The United States has a

different kind of accounting system than the United Kingdom or Germany. These

countries each have different policy standards and regulatory requirements.

However, even within a country such as the United States, the way that health

care com-panies report financial data is different from how banks report their

data to the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC). Even the meaning of

the term cash is different in various

countries and industries. To further emphasize the need for local taxonomies,

within industries and geographies, such as United States banking, there are

different users who demand different kinds of reports. The tax administrator,

controller, and investor relations officer all deal with different report

requirements. Therefore, XBRL provides a mechanism not only to unify data exchange

but also to bring together these various communities. In that manner, XBRL is

actually two languages: one for financial “facts” that are standardized and one

for financial “concepts” that are defined by communities.

Those that read the XBRL specification will find an interesting set of

words used fre-quently, including taxonomy,

item, and tuple. Many of these definitions are different from how other

groups define these terms, so a careful reading of the definitions is

nec-essary for a complete understanding of the specification. XBRL defines a taxonomy as an XML Schema instance that

defines new elements that correspond

to concepts referenced in XBRL documents. XBRL taxonomies can be regarded as

extensions of the XML

Schema utilizing XML Link–based information. An important taxonomy

utilized in many XBRL implementations is the set of elements that correspond to

well-defined concepts within the U.S. Generally Accepted Accounting Principles

(GAAP) applied to Commercial and Industrial (C&I) companies. That taxonomy

includes concepts of “Accounts Receivable Trade, Gross,” “Allowance for

Doubtful Accounts,” and “Accounts Receivable Trade, Net.” An item corresponds to a fact that is

usually, but not necessarily, a numeric fact being reported with respect to a

given period of time about a given busi-ness entity. For example, company

XYZQ’s revenue of $7 million for the year 1998 is a numeric item, whereas a

paragraph of text describing the principles of consolidation used to combine

reports from the subsidiaries of XYZQ is a nonnumeric item. Tuples join these facts into logical

groups so that they can be understood. The combination of the name, age, and

compensation of a director of a company is an example of a tuple. On a similar

note, an XBRL group is a less strictly

combined set of related items that

can appear in any order and can be interspersed among other text and elements

in any XML document. Using the notion of the group, the specification avoids

the direct creation of an XBRL document type. Rather, XBRL items can be

embedded in any well-formed XML document, such as a press release or business

document.

Within an XBRL document, there can be any number of XBRL items that

refer to any number of taxonomies, although each individual item can itself

only refer to only one taxonomy. Taxonomies can be composed together to extend

other taxonomies. For exam-ple, the Financial Reporting for Commercial and

Industrial Companies and U.S. GAAP taxonomies can be extended to include the

term physician salaries, which extends

the concept “expenses” that already exists there.

An XBRL taxonomy document is a valid instance of an XML Schema document.

In fact, two XBRL schemas are imported by a taxonomy: the XBRL instance

document schema, which defines abstract elements such as item and tuple, and the

XBRL datatype schema, which defines XBRL standard data types, such as

“monetary.” See Listing 22.1 for a sample XBRL taxonomy definition and Listing

22.2 for a sample XBRL instance.

LISTING 22.1 XBRL Sample Taxonomy

Element

<element name=”statements.accountantsReport” type=”string”>

<annotation>

<documentation>Report(s)

issued by independent accountant or internal accountant. If two reports are

issued, two accountant report sections should appear</documentation>

<appinfo>

<xbrl:rollup to=”statements” weight=”0”

order=”3” /> <xbrl:label xml:lang=”en”>Accountant’s

Report</xbrl:label> <xbrl:reference name=”SAS” number=”58” chapter=””

paragraph=”” subparagraph=”” />

</appinfo>

</annotation>

</element>

LISTING 22.2 XBRL Sample Instance

(Truncated for Brevity)

<?xml version=”1.0” encoding=”utf-8”?> <group

xmlns=”http://www.xbrl.org/core/xbrl-2000-07-31”

xmlns:ci=”http://www.xbrl.org/us/gaap/ci/2000-07-31”

xmlns:gpsi=”http://www.xbrl.org/us/gaap/ci/2000-07-31/sample” xmlns:csh=”http://www.xbrlSolutions.com/labels”

id=”XXXXXXXXXX-AB”

entity=”NASDAQ:GPSI” period=”1999-05-31”

schemaLocation=”http://www.xbrl.org/us/gaap/ci/2000-07-31

http://www.xbrl.org/us/gaap/ci/2000-07-31/us-gaap-ci-2000-07-31.xsd

http://www.xbrl.org/us/gaap/ci/2000-07-31/sample

http://www.xbrl.org/us/gaap/ci/2000-07-31/sample/gpsi-custom-2000-07-31.xsd”

scaleFactor=”3”

precision=”9”

type=”statements”

unit=”ISO4217:USD”

decimalPattern=”#.#”

formatName=””>

…

<!--Revenues

-->

<group type=”ci:grossProfit.salesRevenueNet”>

<group type=”ci:salesRevenueGross.goods”>

<label href=”xpointer(..)”

xml:lang=”en”>License</label> <item id=”IS-001”

period=”P1Y/1999-05-31”>79685</item> <item id=”IS-002”

period=”P1Y/1998-05-31”>52949</item> <item id=”IS-003” period=”P1Y/1997-05-31”>35919</item>

</group>

<group

type=”ci:salesRevenueGross.services”>

<label href=”xpointer(..)”

xml:lang=”en”>Service</label> <item id=”IS-004”

period=”P1Y/1999-05-31”>55222</item> <item id=”IS-005”

period=”P1Y/1998-05-31”>32710</item> <item id=”IS-006”

period=”P1Y/1997-05-31”>21201</item>

</group>

<label href=”xpointer(..)” xml:lang=”en”>Total

revenues</label> <item id=”IS-007”

period=”P1Y/1999-05-31”>134907</item>

<item id=”IS-008” period=”P1Y/1998-05-31”>85659</item>

<item id=”IS-009” period=”P1Y/1997-05-31”>57120</item>

</group>

…

<!-- End of document group -->

</group>

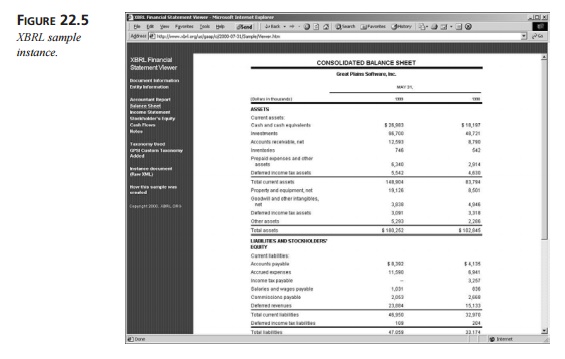

The results of this document are shown in Figure 22.5.

As you may have noticed, critical information is being contained and

exchanged within XBRL. You would think that security would be a primary

concern, but it’s not even a consideration. The primary reason for this is that

the group working with and managing the XBRL effort believes that other groups

will solve this problem in a more complete and widely adopted manner.

Therefore, XBRL will leverage those specifications when they become available.

XBRL is becoming increasingly widely supported. Its presence has spread

the globe and has gotten support from such major establishments as the Securities

Exchange Commission (SEC), the International Accounting Standards Board (IASB),

and the International Federation of Accountants (IFACT). Every company and

every industry in the world will soon use XBRL. As of October 2001, about 20

countries are getting involved with XBRL-based information exchange. In

addition, the XBRL specification is increasingly working with other standards

efforts to be the de facto standard for financial reporting within those other

standards efforts. XBRL has formed connections with such notable standards as

Health Level Seven (HL7), RosettaNet, Research Information Exchange Markup

Language (RIXML), Investor Research Markup Language (IRML), and other efforts.

Even though financial services users use XBRL, it is not exclusively about

financial services. Users of the specification include government agencies,

pharma-ceutical companies, and manufacturing companies. Part of the reason for

XBRL’s wide-spread adoption is its rigorous requirements for working group

members. Any group that wants to become an XBRL working group member must

commit significant financial, technical, and public relations resources, as

well as commit to incorporating XBRL in all of its financial reporting

applications, both internal and external. These requirements ensure that the

specification isn’t merely given lip service.

Interactive Financial Exchange (IFX)

One of the most intensive uses of information in the financial sector is

the exchange of transactional financial data. Transactional data is the day-to-day,

minute-to-minute exchange of individual financial information such as funds

transfers, stock purchases, credit inquiries, and other such information vital

to a working economy. Given the vast quantity and importance of this data, it

is no wonder that XML is increasingly being used to simplify and enhance the

exchange of this information.

In particular, the Interactive Financial Exchange (IFX) specification

provides a robust, scalable framework for the exchange of financial data and

instructions. Even though the current implementation of IFX is in the XML

format, the core specification is independent of a particular representational

technology. Participating in the definition of this format are major financial

players, service providers, and information technology vendors. IFX builds on

previous industry experience, including the Open Financial Exchange (OFX) and

GOLD specifications, which are currently implemented by finan-cial institutions

and service providers to enable electronic exchange of financial data between

them and their customers. IFX didn’t start out as an XML specification but

rather as a generalized business messaging specification for financial

transactions. It just was that XML was able to meet its needs before any other

representational technology. Work on IFX has been going on for about four

years. The IFX Forum is an open-mem-bership, nonprofit corporation founded to

maintain and facilitate the development of the IFX specifications. Current IFX

Forum members include Microsoft, Checkfree, Bank of America, Wells Fargo,

Citigroup, and Avalon.

Specifically, the IFX specification enables the exchange of online

financial services information. The activities supported by IFX include bank,

brokerage, mutual fund, and credit card statement downloads as well as

electronic funds transfers, including recurring transfers, individual and

recurring consumer and business payments, transaction history, current

holdings, balances, and electronic bill presentment and payment. These

transac-tions occur between a broad range of user types, known as service providers, including banks,

brokerage houses, insurance companies, merchants, payment and bill processors,

financial advisors, and government agencies.

The IFX specification also provides a certain amount of transaction and

security robust-ness, as is necessary for the nature of the documents being

exchanged. These features assure users that IFX messages are reliably executed,

the information supplied is correct, and the results can be used for communicating

and executing important financial transac-tions. IFX provides an suite of

security options for further protecting the integrity of financial

transactions. These security features include authentication of the parties

involved, encryption of data, integrity of the information being exchanged, as

well as robust protocols for error recovery.

The IFX specification is an XML messaging protocol that has two key

parts: the infra-structure for sending financial messages and the specific

content of those messages. The infrastructure concerns interparty communication

within and outside company walls and provides common data elements and

security. The specific content is focused on loans and credit, electronic bill

presentment, and business and consumer banking needs.

IFX is a “message-oriented” standard in that the documents are used in a

request/ response mechanism. Clients send IFX message “requests” to servers

that understand the format, which in turn return IFX message “responses” back

to the client. As such, the IFX specification functions as a protocol that can

be used in either batch or interactive communication styles. However, IFX is

also transport neutral, supporting HTTP, SMTP, FTP, or any emergent protocol

for exchange. IFX applies a single authentication context to multiple requests

in order to reduce the overhead of user authentication. With an inter-national

focus, IFX supports multiple currencies, country-specific extensions, and

differ-ent forms of encoding, such as Unicode.

IFX can be transmitted in an asynchronous or synchronous mode. This

means that IFX messages can be sent without keeping the connection open for a

response, or the connec-tion session can wait for the transaction to be

completed before terminating. This feature allows IFX servers the ability to

complete a response at a later time. Sample IFX messages can be seen in

Listings 22.3 and 22.4.

LISTING 22.3 Sample IFX Request Message

POST

http://www.CSP.com/IFX.cgi

HTTP/1.0

User-Agent:MyApp 5.0

Content-Type: text/xml

Content-Length: 1032

<?xml version=”1.0” encoding=”UTF-8” ?>

<?ifx version=”1.0.1” oldfileuid=”00000000-0000…” newfileuid=”00000000-0000…” ?>

<!DOCTYPE IFX PUBLIC “-//IFX//DTD IFX1.0.1//EN”

“http://www.ifxforum.org/IFX1.0.1/xml/ifx.dtd” [private markup]>

<IFX>” \>

... IFX

requests ...

</IFX>

LISTING 22.4 Sample IFX Response Message

HTTP 1.0 200 OK

Content-Type: text/xml

Content-Length: 8732

<?xml version=”1.0” encoding=”UTF-8” ?>

<?ifx version=”1.0.1” oldfileuid=”00000000-0000…” newfileuid=”00000000-0000…” ?>

<!DOCTYPE IFX PUBLIC “-//IFX//DTD IFX1.0.1//EN”

“http://www.ifxforum.org/IFX1.0.1/xml/ifx.dtd” [private markup]>

<IFX>” \> <Status>passed</Status>

<AcctId>1234567890</AcctId> </IFX>

As you probably noticed, this message and the previous message are very

similar. This is intentional. IFX request and response messages are relatively

symmetric documents that can be exchanged by any party in a financial

transaction.

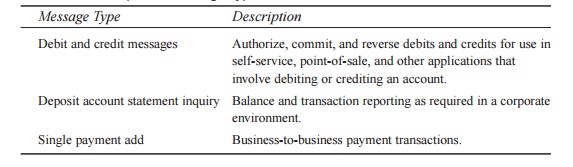

IFX actually consists of a number of separate message types that address

different needs. Table 22.1 lists some of those message types and the sorts of

messages they describe.

TABLE 22.1 Sample IFX Message Types

The IFX framework is made up of implementation rules. Two communicating

parties use the self-discovery features of IFX to exchange information about

what they can and can’t support for transactions. For example, a

bill-presentment client needs to interact with a server that handles payments.

Subsequent development on the IFX specification has concentrated on

adding substantial support for additional features, such as

business-to-business and ATM transactions, including credit, debit, and

management of “value media,” such as stamps, dollar bills, and tickets. In

general, the IFX specification is adding capabilities to support richer forms

and types of payment that can be individually transmitted or conglomerated for

payment in an aggregated fashion, such as payroll transactions.

IFX is also working in the loan credit application space and working

with the insurance vertical industry standard, ACORD. In its next major v2.0

release, the IFX Forum is seri-ously considering how to better incorporate Web

Services, and thinking about using SOAP as a transport mechanism.

Related Topics