Chapter: Basic Radiology : Radiology of the Breast

Exercise: The First Mammogram(The Asymptomatic Patient)

THE ASYMPTOMATIC PATIENT

EXERCISE 5-3. THE FIRST MAMMOGRAM

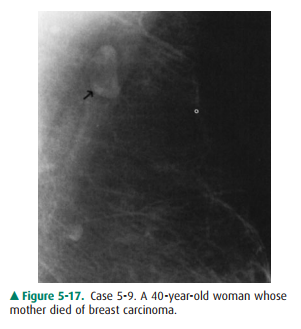

5-9. According to the

American Cancer Society, the best program of breast screening for this woman in

Case 5-9 (Figure 5-17) includes all of the following except

A.

yearly MRI.

B.

yearly mammograms.

C.

cessation of routine mammograms at age 65.

D.

annual clinical breast examination.

5-10. The most likely

diagnosis in Case 5-10 (Figure 5-18) is

A.

complex cyst.

B.

fibroadenolipoma.

C.

galactocele.

D.

ductal carcinoma.

E.

oil cyst.

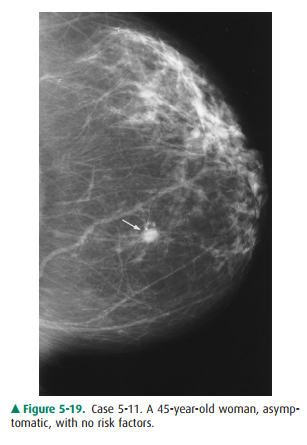

5-11. The differential

diagnosis in Case 5-11 (Figure 5-19) includes all of the following except

A.

invasive ductal carcinoma.

B.

cyst.

C.

intraductal comedocarcinoma.

D.

fibroadenoma.

E.

mucinous carcinoma.

Radiologic Findings

5-9. Detail of mammogram

of the patient in this case shows a smoothly marginated small mass with a

lucent center (arrow) (C is the correct answer to Question 5-9).

5-10. The mammogram in

this case shows a circumscribed mass (arrows) with internal lucency as well as

opacity (B is the correct answer to Question 5-10).

5-11. Mammogram of

patient in this case shows a nodular density (arrow), with indistinct margins

(C is the correct answer to Question 5-11).

Discussion

In Case 5-9, the 40-year-old

woman has a strong family his-tory of breast cancer, which puts her at high

risk for develop ing the disease. As was stated in the introduction to this

chap-ter, controversy exists concerning when mammographic screening should be initiated

and the appropriate frequency of examinations in different groups. Most experts

agree, however, that patients with a strong family history will bene-fit from

screening beginning at age 40. The American Cancer Society (ACS) recommends

annual screening from age 40 in all female patients; therefore, B is not the

correct answer.

Although the upper age limit for

mammographic screen-ing has not been defined, we certainly cannot recommend

cessation over age 65, because the prevalence of breast cancer is greatest in

women in their 50s and 60s. Current ACS guide-lines recommend yearly mammograms

for all women over the age of 40 years. Appropriate age for termination of

screening is best judged by the patient’s physician, weighing life expectancy

against potential benefits from screening.

ACS recommends annual screening

MRI in women at high risk for breast cancer. ACS also recommends yearly

physical examination by the physician to detect tumors missed by mammography,

as well as those that become de-tectable between routine mammograms (interval

cancers). Therefore, A and D are not correct answers to Question 5-9.

This patient’s mammogram is

normal and demonstrates a typical normal lymph node. The node is smoothly

mar-ginated and has a fatty hilum, indicated by the darker center.

In Case 5-10, there is a

circumscribed mass in the axillary tail of this breast. The key to diagnosis is

the mixture of den-sities within the lesion. There are medium-density opacities

interspersed with lucencies within a smoothly marginated mass. This appearance

is pathognomonic for a fibroadeno-lipoma, sometimes called by the misnomer

hamartoma. Being composed of elements of normal breast (fatty, glandu-lar, and

fibrous tissues) organized within a thin capsule, a fi-broadenolipoma forms a

“breast within a breast.” As such, it is benign and needs no further

evaluation. It may be palpable as a soft mass.

The point to remember here is

that fat-containing masses are always benign. Answer D, ductal carcinoma, is

incorrect. The differential diagnosis of a fatty mass, besides

fibroadenolipoma, includes lymph node, as in Case 5-9, galactocele, lipoma, and

oil cyst. Galactoceles are usually smaller and are most commonly seen in

lactating women (Answer C is incorrect).

Oil cysts result from fat

necrosis and are usually smaller. Typically, they are entirely lucent, as they

are filled with oil, except for a thin wall (Answer E is incorrect).

Option A, complex cyst, is

incorrect because this entity would not contain fat. A cyst, whether it contains

serous fluid, blood, or pus, is always opaque and of low to high den-sity, not

lucent.

In Case 5-11, an asymptomatic

45-year-old woman’s first mammogram shows a 1-cm nodule centrally located in

this breast. The differential diagnosis remains broad without fur-ther studies

to help characterize this nodule. All choices ex-cept option C, intraductal

comedocarcinoma, may have this appearance. Intraductal carcinoma, when not

mammo-graphically occult, usually appears as microcalcifications. Be-cause the

margins are indistinct, however, the patient must be recalled for additional

imaging to rule out carcinoma.

The sonographic image shows a

solid lesion, ruling out a simple cyst. Spot compression is then used to

evaluate the borders. If all margins were to appear smooth, one acceptable

course of action would be serial 6-month follow-up mam-mograms for a period of

2 years to demonstrate stability. If any change occurs during this time, biopsy

is indicated.

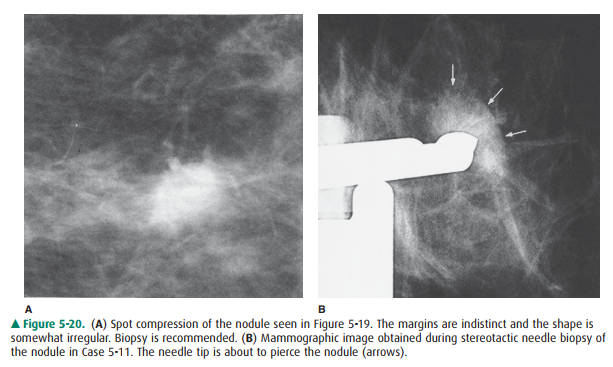

Spot compression (Figure 5-20 A)

reveals that portions of the border are not smooth, raising the level of

suspicion for malignancy. To exclude carcinoma, biopsy is needed.

Biopsy may be accomplished with

excision or with needle biopsy. Excision would require needle localization of

the nodule for the surgeon, because this is a nonpalpable lesion. Core needle

biopsy, either stereotactic or ultrasound-guided, is preferable because it is

minimally invasive, causes less mor-bidity to the patient, leaves no distortion

in the breast or on the skin, and is often less expensive than surgical

excision. Accurate needle biopsy devices, however, are expensive and are not

universally available.

This nodule was diagnosed as a

fibroadenoma with stereotactic core needle biopsy (Figure 5-20 B).

Fibroadeno-mas are very common and are frequently the cause of benign breast

biopsy. They occur in very young women (teenagers and women under 30 years of

age) and persist undiscovered through the age at which the first mammogram is

obtained, then, upon discovery, become a concern of both physician and patient.

They may also become palpable or mammo-graphically visible in older women after

previously normal mammograms. They continue to be a management problem, because

fibroadenoma and carcinoma have overlapping mammographic features and both are

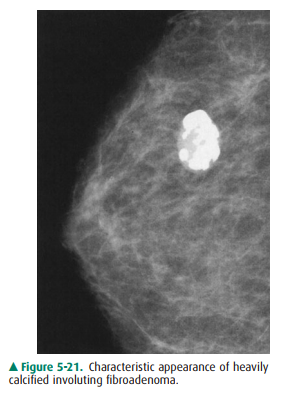

common lesions in middle-aged women. With age, fibroadenomas become invo-luted

and heavily calcified, thereby revealing their true iden-tity (Figure 5-21).

Without this appearance, however, biopsy is often necessary.

A high index of suspicion and careful

evaluation, together with either close follow-up or liberal use of needle

biopsy, are needed to minimize both false-negative impressions and ex-cessive

breast surgery.

Related Topics