Chapter: Obstetrics and Gynecology: Cancer of the Uterine Corpus

Endometrial Cancer

ENDOMETRIAL CANCER

Endometrial carcinoma is

typically a disease of post-menopausal women. Between 15% and 25% of postmenopausalwomen with bleeding have

endometrial cancer. A majority ofcases are diagnosed while in stage I

(72%). Despite recog-nition at early stages, endometrial cancer is the eighth

leading site of cancer-related mortality among women in the United States.

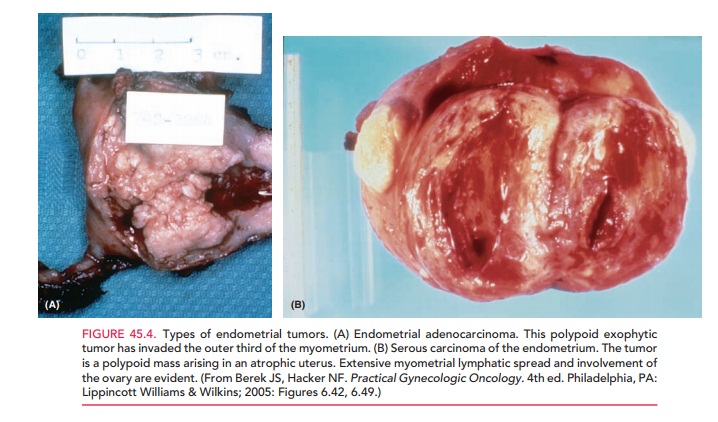

Most primary endometrial carcinomas are adenocar-cinomas (Fig. 45.4).

Because squamous epithelium may coexist with the glandular

elements in an adenocarcinoma, descriptive terms that include the squamous

element may be used. In cases where the squamous element is benign and makes up

less than 10% of the histologic picture, the term adenoacanthoma is used. Uncommonly, the squamous ele-ment may

appear malignant on histologic assessment and is then referred to as adenosquamous carcinoma. Other

descriptions, such as clear cell

carcinoma and papillaryserous

adenocarcinoma, may be applied, depending on thehistologic architecture.

All of these carcinomas are consid-ered under the general category of

adenocarcinoma of the endometrium and are treated in a similar manner.

Pathogenesis and Risk Factors

Two kinds of endometrial carcinoma

have been identified. Type I endometrial carcinoma is “estrogen-dependent” and accounts for approximately 90% of cases. It

is most commonly caused by an excess of estrogen unopposed by progestins. These

cancers tend to have low-grade nuclear atypia, endometrioid cell types, and an

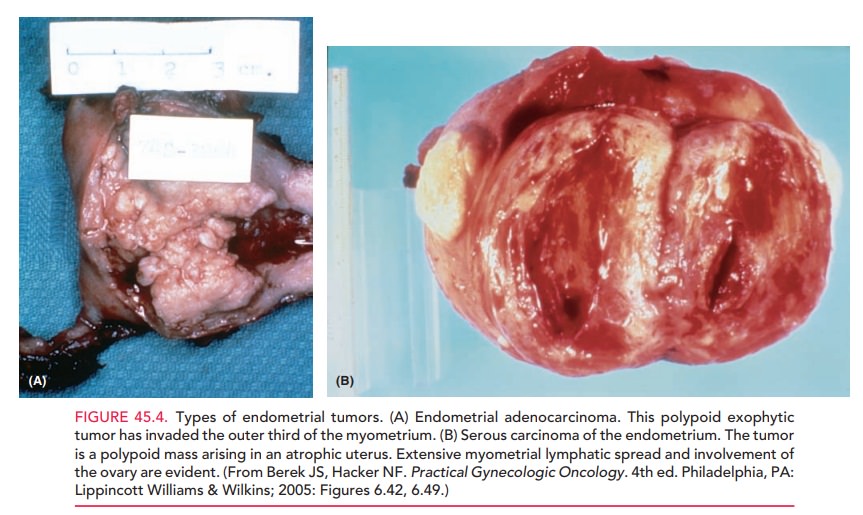

overall favorable prognosis. The second type, Type II or “estrogen-independent” endometrial carcinoma, occurs sponta-neously,

characteristically in thin, older postmenopausal women without unopposed

estrogen excess, arising in an atrophic endometrium rather than a hyperplastic

one. These cancers tend to be less well-differentiated, with a

Estrogen-independent cancer is less com-mon than estrogen-dependent cancer.

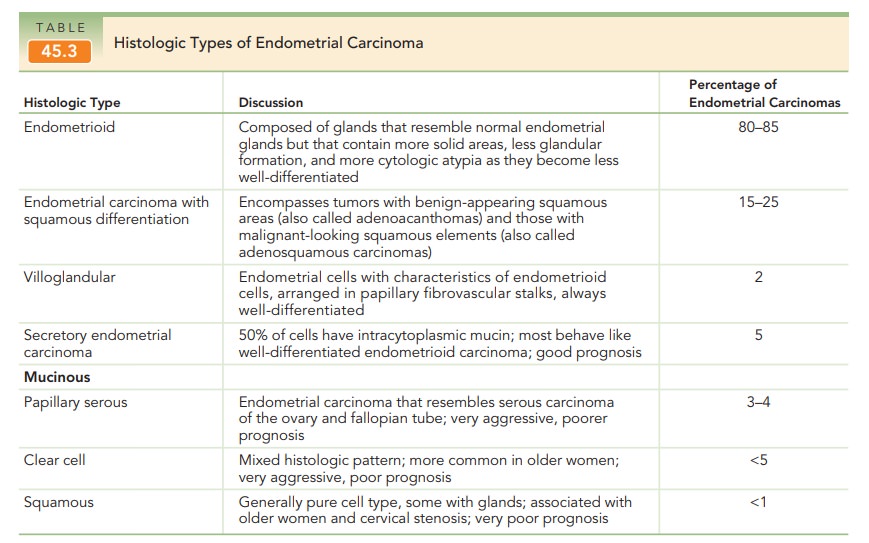

Unusual histologic subtypes, including papillary serous adenocarcinoma and

clear cell adenocarcinoma of the endometrium, tend to be more aggressive than

the more common adenocarcinoma (Table 45.3).

Endometrial

carcinoma usually spreads throughout the endometrial cavity first and then

begins to invade the myometrium, endocervical canal, and eventually the

lymphatics. Hematogenous spread occurs with endometrial

carcinoma more readily than in cervical cancer or ovarian cancer. Invasion of

adnexal structures may occur through lymphat-ics or direct implantation through

the fallopian tubes. After extrauterine spread to the peritoneal cavity, cancer

cells may spread widely in a fashion similar to that of ovarian cancer.

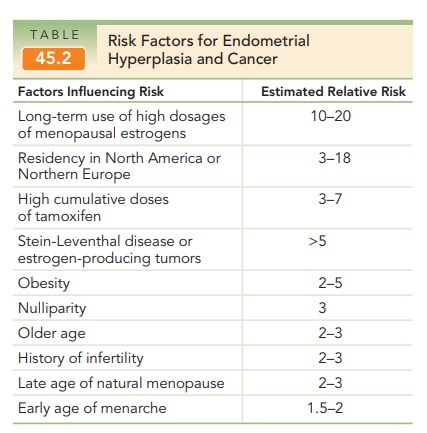

As mentioned earlier, the risk

factors for developing endometrial cancer are identical to those for

endometrial hyperplasia (see Table 45.2).

Diagnosis

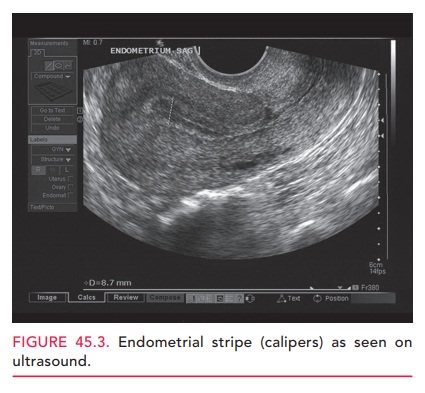

Endometrial

sampling, prompted by vaginal bleeding, most frequently establishes the

diagnosis of endometrial cancer. Vaginal bleeding or discharge is

the only presenting complaint in 80% to 90% of women with endometrial

carcinoma. In some, often older patients, cervical ste-nosis may sequester the

blood in the uterus, with the presentation being hematometra or pyometra and a

puru-lent vaginal discharge. In more advanced disease, pelvic dis-comfort or an

associated sensation of pressure caused by uterine enlargement or extrauterine

disease spread may accompany the complaint of vaginal bleeding or even be the

presenting complaint. Fewer than 5% of

women found to haveendometrial carcinoma are actually asymptomatic.

Special

consideration should be given to the patient who pre-sents with postmenopausal bleeding (i.e., bleeding

that occurs after 6 months of amenorrhea in a patient who has been diagnosed as

menopausal).

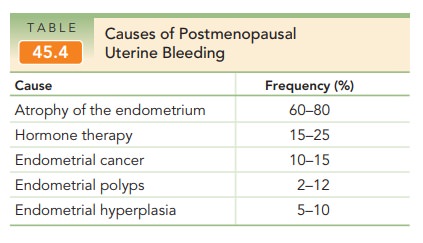

In this group of patients, it is

mandatory to assess the endometrium histologically because the risk of

endometrial carcinoma is approximately 10% to 15%, although other causes are

more common (Table 45.4). Other gynecologic assessments should also be made,

including careful physical and pelvic examination, as well as a screening Pap

smear. Preoperative measurement of the CA

125 level may be appropri-ate, because it is frequently elevated in women with

advanced-stage disease. Elevated levels of CA 125 may assist in

predictingtreatment response or in posttreatment surveillance.

Prognostic Factors

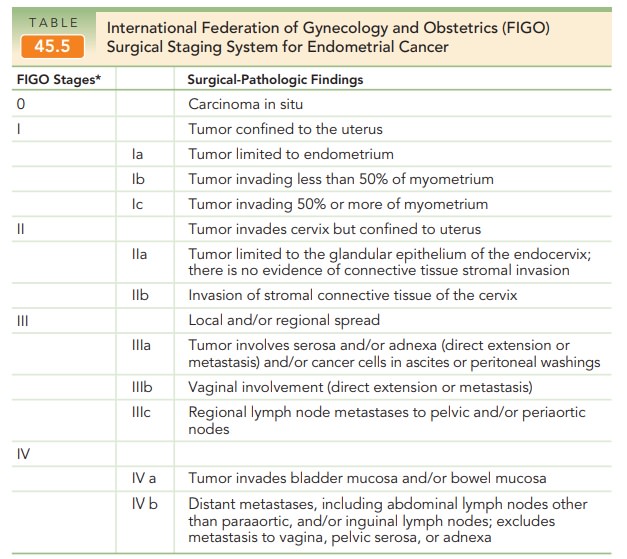

The current International

Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) staging of endometrial cancer

(adopted in 1988) lists three grades of endometrial carcinoma:

·

G1 is well-differentiated

adenomatous carcinoma (less than 5% of the tumor shows a solid growth pattern).

·

G2 is moderately differentiated

adenomatous carcinoma with partly solid areas (6% to 50% of the tumor shows a

solid growth pattern).

·

G3 is poorly differentiated or

undifferentiated (greater than 50% of the tumor shows a solid growth pattern).

Most patients with endometrial

carcinoma have G1 or G2 lesions by this classification, with 15% to 20% having

undifferentiated or poorly differentiated G3 lesions.

The FIGO staging system

incorporates elements correlated with prognosis and risk of recurrent disease—

histologic grade, nuclear grade, depth of myometrial inva-sion, cervical

glandular or stromal invasion, vaginal and adnexal metastasis, cytology status,

disease in the pelvic and/or paraaortic lymph nodes, and presence of distant

metastases (Table 45.5). The single most important prog-nostic factor for

endometrial carcinoma is histologicgrade.

Histologically, poorly differentiated or undiffer-entiated tumors are

associated with a considerably poorer prognosis because of the likelihood of

extrauterine spread through adjacent lymphatic and peritoneal fluid. Depthof myometrial invasion is the

second most importantprognostic factor.

Survival

rates vary widely, depending on the grade of tumor and depth of penetration

into the myometrium. A patient with aG1 tumor that

does not invade the myometrium has a 95% 5-year survival rate, whereas a

patient with a poorly differ-entiated (G3) tumor with deep myometrial invasion

may have a 5-year survival rate of only 20%.

Treatment

Hysterectomy

is the primary treatment of endometrial cancer. The addition of complete

surgical staging with an assessment of retroperitoneal lymph nodes is not only

therapeutic, but also is associated with improved survival.

Complete surgical staging

includes pelvic washings, bilat-eral pelvic and paraaortic lymphadenectomy, and

com-plete resection of all disease. Sampling of the common iliac nodes,

regardless of depth of penetration or histo-logic grade, may provide further

information about the histologic grade and depth of invasion. Palpation of

lymph nodes is equally inaccurate and should not substitute sur-gical resection

of nodal tissue for histopathology.

Exceptions to the need for

surgical staging include young or perimenopausal women with grade 1

endometri-oid adenocarcinoma associated with atypical endometrial hyperplasia,

and women at increased risk for mortality secondary to comorbidities. Women in

the former group who desire to maintain their fertility may be treated with

high-dose progestin monitored by serial endometrioid sampling. Women in the

latter group may be treated with vaginal hysterectomy. In ultra-high-risk

surgical patients, therapeutic radiation may be used as primary treatment,

although results are suboptimal.

Postoperative radiation therapy should be tailored to known metastatic disease or used in cases of recurrence. In patients with surgical stage I disease, radiation therapy may reduce the risk of recurrence, but does not improve survival. For women with positive lymph nodes (stage IIIc) disease, radia-tion therapy is critical in improving survival rates. Women withintraperitoneal disease are treated with surgery, followed by systemic chemotherapy or radiation therapy or both.

Recurrent Endometrial Carcinoma

Postoperative surveillance for

women who have not received radiation therapy involves speculum and

recto-vaginal examinations every 3 to 4 months for 2 to 3 years, and then twice

a year to detect pelvic recurrent disease, particularly in the vagina. Women who have received radia-tion therapy

have a decreased risk of vaginal recurrence as well as fewer therapeutic

options to treat recurrence. Therefore, these women benefit less from frequent

surveillance with cervical cytology screening and pelvic examinations for

detection of recurrent disease.

Recurrent endometrial carcinoma

occurs in about 25% of patients treated for early disease, one-half within 2

years, and three-fourths within 3 to 4 years. In general, those with recurrent

vaginal disease have a better prog-nosis than those with pelvic recurrence, who

in turn fare better than those with distant metastatic disease (lung, abdomen,

lymph nodes, liver, brain, and bone).

Recurrent

estrogen-dependent or progestin-dependent cancer may respond to high-dose progestin therapy. A major

advantage of high-dose progestin therapy is its minimal compli-cation rate.

Chemotherapy with doxorubicin, cisplatin, and paclitaxel produces occasional

favorable short-term results, but long-term remissions with these therapies are

rare.

Hormone Therapy after Treatment for Endometrial Carcinoma

The use of estrogen therapy in patients previously treated for endometrial

carcinoma has long been considered con-traindicated because of the concern that

estrogen might activate occult metastatic disease.

Hormone

therapy can be used in the presence of the same indications as for any other

woman, except that the selection of appropriate candidates for estrogen

treatment should be based on prognostic indicators and the patient must be

willing to assume the risk. Cautious individualized

assessment of risks and benefits should therefore be made on a case-by-case

basis.

Related Topics