Chapter: Medical Physiology: Physical Principles of Gas Exchange; Diffusion of Oxygen and Carbon Dioxide Through the Respiratory Membrane

Effect of the Ventilation-Perfusion Ratio on Alveolar Gas Concentration

Effect of the Ventilation-Perfusion Ratio on Alveolar Gas Concentration

In the early, we learned that two factors determine the PO2 and the PCO2 in the alveoli: (1) the rate of alveolar ventilation and (2) the rate of trans-fer of oxygen and carbon dioxide through the respira-tory membrane. These earlier discussions made the assumption that all the alveoli are ventilated equally and that blood flow through the alveolar capillaries is the same for each alveolus. However, even normally to some extent, and especially in many lung diseases, some areas of the lungs are well ventilated but have almost no blood flow, whereas other areas may have excellent blood flow but little or no ventilation. In either of these conditions, gas exchange through the respiratory mem-brane is seriously impaired, and the person may suffer severe respiratory distress despite both normaltotal ventilation and normal total pulmonary blood flow, but with the ventilation and blood flow going to different parts of the lungs. Therefore, a highly quantitative concept has been developed to help us understand res-piratory exchange when there is imbalance between alveolar ventilation and alveolar blood flow. This concept is called the ventilation-perfusion ratio.

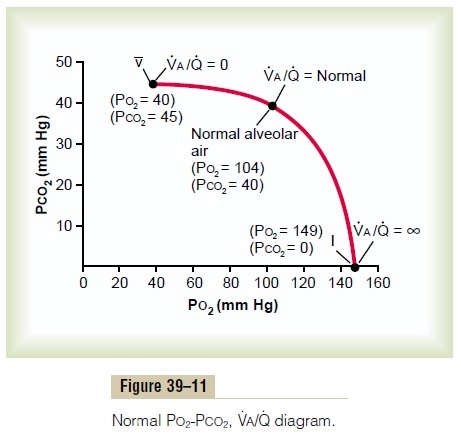

Alveolar Oxygen and Carbon Dioxide Partial Pressures When Va/Q Equals Zero. When VA/Q is equal to zero—that is, withoutany alveolar ventilation—the air in the alveolus comes to equilibrium with the blood oxygen and carbon dioxide because these gases diffuse between the blood and the alveolar air. Because the blood that perfuses the capillaries is venous blood returning to the lungs from the systemic circulation, it is the gases in this blood with which the alveolar gases equilibrate. We will learn that the normal venous blood (v¯) has a PO2 of 40 mm Hg and a PCO2 of 45 mm Hg. Therefore, these are also the normal partial pressures of these two gases in alveoli that have blood flow but no ventilation.

Alveolar Oxygen and Carbon Dioxide Partial Pressures When VA/Q Equals Infinity. The effect on the alveolar gas partial pres-from the effect when VA/Q equals zero because now there is no capillary blood flow to carry oxygen away or to bring carbon dioxide to the alveoli. Therefore, instead of the alveolar gases coming to equilibrium with the venous blood, the alveolar air becomes equal to the humidified inspired air. That is, the air that is inspired loses no oxygen to the blood and gains no carbon dioxide from the blood. And because normal inspired and humidified air has a PO2 of 149 mm Hg and a PCO2 of 0 mm Hg, these will be the partial pressures of these two gases in the alveoli.

Gas Exchange and Alveolar Partial Pressures When VA/QIs Normal. When there is both normal alveolar ventilationand normal alveolar capillary blood flow (normal alve-olar perfusion), exchange of oxygen and carbon dioxide through the respiratory membrane is nearly optimal, and alveolar PO2 is normally at a level of 104 mm Hg, which lies between that of the inspired air (149 mm Hg) and that of venous blood (40 mm Hg). Likewise, alveolar PCO2 lies between two extremes; it is normally 40 mm Hg, in contrast to 45 mm Hg in venous blood and 0 mm Hg in inspired air. Thus, under normal conditions, the alveolar air PO2 averages 104 mm Hg and the PCO2averages 40 mm Hg.

PO2-PCO2, VA/Q Diagram

The concepts presented in the preceding sections can beshown in graphical form, as demonstrated in Figure39–11, called the Po2-Pco2, Va/Qdiagram. The curve inthe diagram represents all possible Po2 and Pco2 combinationsbetween the limits of V.a/Qequals zero andV .a/Qequals infinity when the gas pressures in thevenous blood are normal and the person is breathing air at sea-level pressure. Thus, point v¯ is the plot of Po2and Pco2 when V.a/Q.equals zero. At this point, the Po2is 40 mm Hg and the Pco2 is 45 mm Hg, which are thevalues in normal venous blood.At the other end of the curve, when V.a/Q.equals infinity,point I represents inspired air, showing Po2 to be 149mm Hg while Pco2 is zero. Also plotted on the curveis the point that represents normal alveolar air whenV . a/Q.is normal. At this point, Po2 is 104 mm Hg andPco2 is 40 mm Hg.

Concept of “Physiologic Shunt” (When VA/Q Is Below Normal). .

Whenever VA/Q is below normal, there is inadequate ventilation to provide the oxygen needed to fully oxy-genate the blood flowing through the alveolar capil-laries. Therefore, a certain fraction of the venous blood passing through the pulmonary capillaries does not become oxygenated. This fraction is called shuntedblood. Also, some additional bloodflows throughbronchial vessels rather than through alveolar capillar-ies, normally about 2 per cent of the cardiac output; this, too, is unoxygenated, shunted blood.

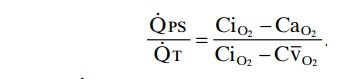

The total quantitative amount of shunted blood per minute is called the physiologic shunt. This physiologic shunt is measured in clinical pulmonary function labo-ratories by analyzing the concentration of oxygen in both mixed venous blood and arterial blood, along with simultaneous measurement of cardiac output. From these values, the physiologic shunt can be calculated by the following equation:

in which . QPS is the physiologic shunt blood flow per minute, QT is cardiac output per minute, CiO2 is the con-centration of oxygen in the arterial blood if there is an “ideal” ventilation-perfusion ratio, CaO2 is the measured concentration of oxygen in the arterial blood, and CV¯O2 is the measured concentration of oxygen in the mixed venous blood.

The greater the physiologic shunt, the greater the amount of blood that fails to be oxygenated as it passesthrough the lungs.

Concept of the “Physiologic Dead Space” (When VA/Q Is Greater Than Normal)

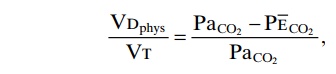

When ventilation of some of the alveoli is great but alveolar blood flow is low, there is far more available oxygen in the alveoli than can be transported away from the alveoli by the flowing blood. Thus, the ventilation of these alveoli is said to be wasted. The ventilation of the anatomical dead space areas of the respiratory pas-sageways is also wasted. The sum of these two types of wasted ventilation is called the physiologic dead space. This is measured in the clinical pulmonary function lab-oratory by making appropriate blood and expiratory gas measurements and using the following equation, called the Bohr equation:

in which VDphys is the physiologic dead space, VT is the tidal volume, PaCO2 is the partial pressure of carbon dioxide in the arterial blood, and PECO2 is the average partial pressure of carbon dioxide in the entire expired air.

When the physiologic dead space is great, much of the work of ventilation is wasted effort because so much ofthe ventilating air never reaches the blood.

Abnormalities of Ventilation- Perfusion Ratio

Abnormal VA/Q in the Upper and Lower Normal Lung. In anormal person in the upright position, both pulmonary capillary blood flow and alveolar ventilation are con-siderably less in the upper part of the lung than in the lower part; however, blood flow is decreased consider- ably more than ventilation is. Therefore, at the top of the lung, VA/Q is as much as 2.5 times as great as the ideal value, which causes a moderate degree of physio-logic dead space in this area of the lung.

At the other extreme, in the bottom of the lung, there is slightly too little ventilation in relation to blood flow, with VA/Q as low as 0.6 times the ideal value. In this area, a small fraction of the blood fails to become normally oxygenated, and this represents aphysiologicshunt.

In both extremes, inequalities of ventilation and perfusion decrease slightly the lung’s effectiveness for exchanging oxygen and carbon dioxide. However, during exercise, blood flow to the upper part of the lung increases markedly, so that far less physiologic dead space occurs, and the effectiveness of gas exchange now approaches optimum.. .

Abnormal VA/Q in Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. Mostpeople who smoke for many years develop various degrees of bronchial obstruction; in a large share of these persons, this condition eventually becomes so severe that they develop serious alveolar air trapping and resultant emphysema. The emphysema in turn causes many of the alveolar walls to be destroyed. Thus,two abnormalities occur in smokers to cause abnormal VA/Q. First, because many of the small bronchioles areobstructed, the alveoli beyond the obstructions are unventilated, causing a VA/Q that approaches zero. Second, in those areas of the lung where the alveolar walls have been mainly destroyed but there is still alveolar ventilation, most of the ventilation is wasted because of inadequate blood flow to transport the blood gases.

Thus, in chronic obstructive lung disease, some areas of the lung exhibit serious physiologic shunt, and other areas exhibit serious physiologic dead space. Both these conditions tremendously decrease the effectiveness of the lungs as gas exchange organs, sometimes reducing their effectiveness to as little as one tenth normal. In fact, this is the most prevalent cause of pulmonary dis-ability today.

Related Topics