Chapter: Modern Pharmacology with Clinical Applications: Drugs Used in Asthma

Drugs Used in Asthma

Drugs Used in Asthma

The word asthma is derived from a Greek word meaning difficulty in

breathing. The clinical expression of asthma varies from a mild intermittent

wheeze or cough to severe chronic obstruction that can restrict normal

activity. Acute asthma attacks are triggered by a variety of stimuli, including

exposure to allergens or cold air, exercise, and upper respiratory tract

infections. Recently, a number of genetic polymorphisms have been associated

with an increased risk of developing asthma. Thus, genetic factors probably

contribute to the exaggerated response of the asthmatic airway to various

environmental challenges. The most severe exacerba-tion of asthma, status asthmaticus, is a life-threatening

condition that requires hospitalization and must be treated aggressively. Unlike

most exacerbations of the disease, status asthmaticus is by definition

unresponsive to standard therapy.

The most important outcomes

for successful therapy of asthma are as follows:

·

Prevent chronic and troublesome symptoms

·

Maintain (near) normal pulmonary function

·

Maintain normal activity levels

·

Prevent recurrent exacerbations of asthma and minimize the need for

emergency department visits or hospitalizations

·

Provide optimal pharmacotherapy with mini-mal or no adverse effects

Pathophysiology

Asthma symptoms are produced

by reversible narrow-ing of the airway, which increases resistance to airflow

and consequently reduces the efficiency of movement of air to and from the

alveoli. In addition to airway ob-struction, cardinal features of asthma include

inflamma-tion and hyperreactivity of the airway. In contrast to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (emphysema

and chronic bronchitis), the airway

obstruction associated with asthma is generally reversible. However, severe

long-standing asthma changes the architecture of the airway. These changes,

including smooth muscle hyper-trophy and bronchofibrosis, can lead to an

irreversible decrement in pulmonary function. These structural changes are

limited to the airways. The lung parenchyma is generally spared.

An aberrant immune response

associated with al-lergy appears to underlie asthma in most children over age 3

years and in most young adults; allergy-induced asthma is also known as extrinsic asthma. In contrast, a large

number of patients, especially those who acquire asthma as older adults, have

no discernible immunolog-ical basis for their condition, although airway

inflamma-tion remains a characteristic of the disease; this type of asthma is

termed intrinsic asthma. Other

patients may have both allergic and nonallergic forms of asthma.

Airway Obstruction

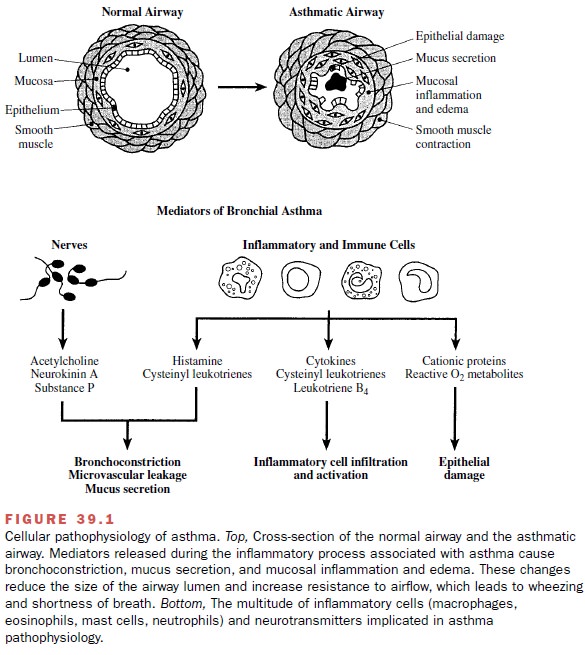

Three factors contribute to

airway obstruction in asthma: (1) contraction of the smooth muscle that

sur-rounds the airways; (2) excessive secretion of mucus and in some, secretion

of thick, tenacious mucus that ad-heres to the walls of the airways; and (3)

edema of the respiratory mucosa. Spasm of the bronchial smooth muscle can occur

rapidly in response to a provocative stimulus and likewise can be reversed

rapidly by drug therapy. In contrast, respiratory mucus accumulation and edema

formation are likely to require more time to develop and are only slowly

reversible.

Airway Inflammation

The recognition that asthma is a disease of airway in-flammation (Fig. 39.1) has fundamentally changed the

Thus, it is useful to discuss the involvement of various

mediators and in-flammatory cells in antigen-induced asthma, an exten-sively

studied, albeit simplistic, model of the disease. In this model, antigens, such

as ragweed pollen or house mite dust, sensitize individuals by eliciting the

produc-tion of antibodies of the immunoglobulin (Ig) E type. These antibodies

attach themselves to the surface of mast

cells and basophils. If the

individual is reexposed to the same

antigen days to months later, the resulting antigen–antibody reaction on lung

mast cells will trigger the release of histamine

and the cysteinyl leukotrienes,

agents that produce bronchoconstriction, mucus secre-tion, and pulmonary edema.

Mast cells also release a va-riety of chemotactic mediators, such as leukotriene B4 and cytokines. These agents recruit and

activate addi-tional inflammatory cells, particularly eosinophils and alveolar

macrophages, both of which are also rich sources of leukotrienes and cytokines.

Ultimately, re-peated exposure to antigen

establishes a chronic inflam-matory state in the asthmatic airway.

Related Topics