Chapter: Modern Pharmacology with Clinical Applications: Drugs Used in Asthma

Antiinflammatory Agents

ANTIINFLAMMATORY

AGENTS

The medical and scientific

communities have recog-nized that asthma

is not simply a disease marked by acute

bronchospasm but rather a complex chronic in-flammatory disorder of the

airways. On the basis of this knowledge,

antiinflammatory agents, particularly corti-costeroids, are now included in the

treatment regimens of an ever-increasing proportion of asthmatic patients.

Corticosteroids

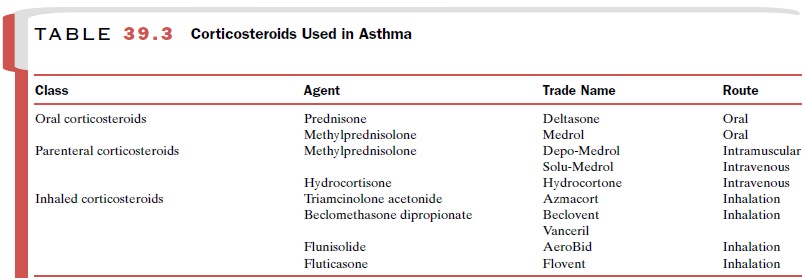

A major breakthrough in

asthma therapy was the intro-duction in the 1970s of aerosol corticosteroids. These agents (Table 39.3) maintain much of

the impressive therapeutic efficacy of parenteral and oral cortico-steroids,

but by virtue of their local administration and markedly reduced systemic

absorption, they are associ-ated with a greatly reduced incidence and severity

of side effects. The success of inhaled steroids has led to a substantial

reduction in the use of systemic cortico-steroids. Inhaled corticosteroids, along with β2-adreno-ceptor agonists, are

front-line therapy of chronic asthma.

Basic Pharmacology

All corticosteroids have the

same general mechanism of action; they traverse cell membranes and bind to a

spe-cific cytoplasmic receptor. The steroid-receptor complex translocates to

the cell nucleus, where it attaches to nu-clear binding sites and initiates

synthesis of messenger ri-bonucleic acid (mRNA). The novel proteins that are

formed may exert a variety of effects on cellular func-tions. The precise

mechanisms whereby the cortico-steroids exert their therapeutic benefit in asthma

remain unclear, although the benefit is likely to be due to several actions

rather than one specific action and is related to their ability to inhibit

inflammatory processes.At the mo-lecular level, corticosteroids regulate the

transcription of a number of genes, including those for several cytokines.

The corticosteroids have an

array of actions in sev-eral systems that may be relevant to their

effectiveness in asthma. These include inhibition of cytokine and mediator

release, attenuation of mucus secretion, up-regulation of β-adrenoceptor numbers,

inhibition of IgE synthesis, attenuation of eicosanoid generation, de-creased

microvascular permeability, and suppression of inflammatory cell influx and

inflammatory processes. The effects of the steroids take several hours to days

to develop, so they cannot be used for quick relief of acute episodes of

bronchospasm.

Clinical Uses

The corticosteroids are

effective in most children and adults with asthma. They are beneficial for the

treat-ment of both acute and chronic aspects of the disease. Inhaled

corticosteroids, including triamcinolone ace-tonide (Azmacort), beclomethasone dipropionate (Beclo-vent, Vanceril), flunisolide (AeroBid), and fluticasone (Flovent), are indicated for maintenance

treatment of asthma as prophylactic therapy. Inhaled corticosteroids are

not effective for relief of acute episodes of severe bronchospasm. Systemic

corticosteroids, including pred-nisone and prednisolone, are used for the

short-term treatment of asthma exacerbations that do not respond to β2-adrenoceptor agonists and

aerosol corticosteroids. Systemic corticosteroids, along with other treatments,

are also used to control status asthmaticus. Because of the side effects

produced by systemically administered corticosteroids, they should not be used

for maintenance therapy unless all other treatment options have been exhausted.

A fixed combination of

inhaled fluticasone and sal-meterol (Advair)

is available for maintenance antiin-flammatory and bronchodilator treatment of

asthma.

Adverse Effects and Contraindications

The side effects of

corticosteroids range from minor to severe and life threatening. The nature and

severity of

side effects depend on the

route, dose, and frequency of administration, as well as the specific agent

used. Side effects are much more prevalent with systemic adminis-tration than

with inhalant administration. The potential consequences of systemic

administration of the corti-costeroids include adrenal suppression, cushingoid

changes, growth retardation, cataracts, osteoporosis, CNS effects and

behavioral disturbances, and increased susceptibility to infection. The

severity of all of these side effects can be reduced markedly by alternate-day

therapy.

Inhaled corticosteroids are

generally well tolerated. In contrast to systemically administered

corticosteroids, inhaled agents are either poorly absorbed or rapidly

metabolized and inactivated and thus have greatly di-minished systemic effects

relative to oral agents. The most frequent side effects are local; they include

oral candidiasis, dysphonia, sore throat and throat irritation, and coughing.

Special delivery systems (e.g., devices with spacers) can minimize these side

effects. Some studies have associated slowing of growth in children with the

use of high-dose inhaled corticosteroids, al-though the results are

controversial. Regardless, the purported effect is small and is likely

outweighed by the benefit of control of the symptoms of asthma.

Care should be taken in

transferring patients from systemic to aerosol corticosteroids, as deaths due

to ad-renal insufficiency have been reported. In addition, al-lergic

conditions, such as rhinitis, conjunctivitis, and eczema, previously controlled

by systemic corticos-teroids, may be unmasked when asthmatic patients are

switched from systemic to inhaled corticosteroids. Caution should be exercised

when taking cortico-steroids during pregnancy, as glucocorticoids are

terato-genic. Systemic corticosteroids are contraindicated in patients with

systemic fungal infections.

Related Topics