Chapter: Clinical Dermatology: Disorders of blood vessels and lymphatics

Disorders involving small blood vessels

Disorders

involving small blood vessels

Acrocyanosis

This

type of ‘poor circulation’, often familial, is more common in females than

males. The hands, feet, nose, ears and cheeks become blue-red and cold. The

palms are often cold and clammy. The condition is caused by arteriolar

constriction and dilatation of the subpapil-lary venous plexus, and to

cold-induced increases in blood viscosity. The best answers are warm clothes

and the avoidance of cold.

Erythrocyanosis

This

occurs in fat, often young, women. Purple-red mottled discoloration is seen

over the buttocks, thighs and lower legs. Cold provokes it and causes an

unpleas-ant burning sensation. An area of acrocyanosis or erythrocyanosis may

be the site where other disorders will settle in the future, e.g. perniosis,

erythema in-duratum, lupus erythematosus, sarcoidosis, cutaneous tuberculosis and

leprosy.

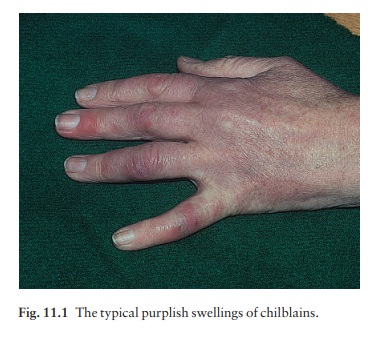

Perniosis (chilblains)

In

this common, sometimes familial, condition, inflamed purple-pink swellings

appear on the fingers, toes and, rarely, ears (Fig. 11.1). They arrive with

winter and are induced by cold. They are painful, and itchy or burning on

rewarming. Occasionally they ulcerate. Chilblains are caused by a combination

of arteriolar and venular constriction, the latter predom-inating on rewarming

with exudation of fluid into the tissues. Warm housing and clothing help.

Topical remedies rarely work, but the oral calcium channel blocker nifedipidine

may be useful. The blood pressure should be monitored at the start of treatment

and at return visits. The vasodilator nicoti-namide (500 mg three times daily)

may be helpful alone or in addition to calcium channel blockers. Sympathectomy

may be advised in severe cases.

Erythromelalgia

This is a rare condition in which the extremities become red, hot and painful when they or their owner are exposed to heat.

The condition may be idiopathic, or caused by a myeloproliferative disease (e.g. poly-cythaemia rubra vera or thrombocythaemia), lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, diabetes, degen-erative peripheral vascular disease or hypertension. Small doses of aspirin give symptomatic relief. Alternatives include non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), α blockers and oxpentifylline (pentoxifylline).

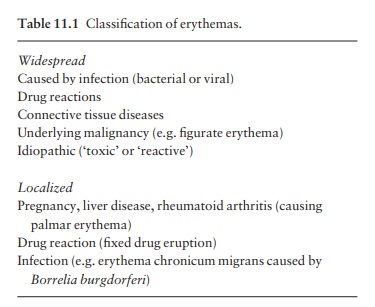

Erythemas

Erythema

accompanies all inflammatory skin condi-tions, but the term ‘the erythemas’ is

usually applied to a group of conditions with redness but without prim-ary

scaling. Such areas are seen in some bacterial and viral infections such as

toxic shock syndrome and measles. Drugs are another common cause . If no cause

is obvious, the rash is often called a ‘toxic’ or ‘reactive’ erythema (Table

11.1).

When

erythema is associated with oedema (‘urticated erythema’) it becomes palpable.

Figurate erythemas

These

are chronic eruptions, made up of bizarre ser-piginous and erythematous rings.

In the past most carried Latin labels; happily, these eruptions are now grouped

under the general term of ‘figurate erythemas’. Underlying malignancy, a

connective tissue disorder, a bacterial, fungal or yeast infection, worm

infestation, drug sensitivity and rheumatic heart disease should be excluded,

but often the cause remains obscure.

Palmar erythema

This

may be an isolated finding in a normal person or be familial. Sometimes it is

seen in pregnancy, liver disease or rheumatoid arthritis. Often associated with

spider telangiectases , it may be caused by increased circulating oestrogens.

Erythema migrans

These

annular erythematous areas are usually solitary, and occur most often on

exposed skin after a tick bite. They expand slowly and may become very large.

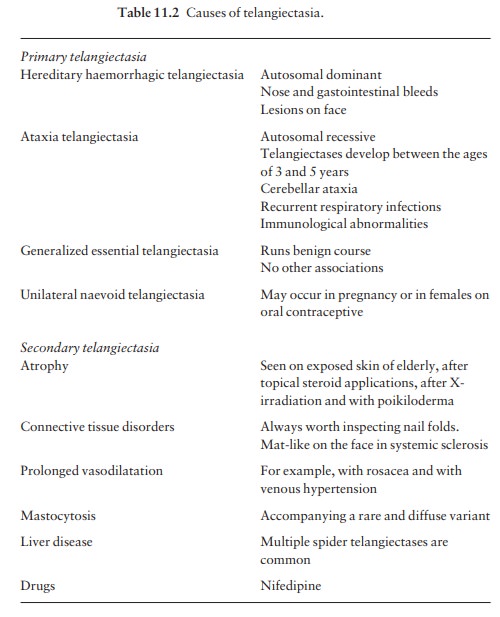

Telangiectases

This

term refers to permanently dilatated and visible small vessels in the skin.

They appear as linear, punctate or stellate crimson-purple markings. The common

causes are given in Table 11.2.

Spider naevi

These

stellate telangiectases do look rather like spiders, with legs radiating from a

central, often palpable, feeding vessel. If the diagnosis is in doubt, press on

the central feeding vessel with the corner of a glass slide and the entire

lesion will disappear. Spider naevi are seen frequently on the faces of normal

children, and may erupt in pregnancy or be the presenting sign of liver

disease, with many lesions on the upper trunk. Liver function should be checked

in those with many spider naevi. The central vessel can be destroyed by

electrodessication without local anaesthesia or with a pulsed dye laser.

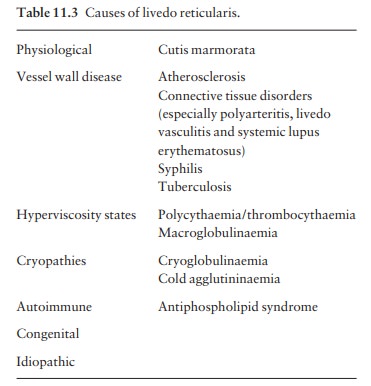

Livedo reticularis

This

cyanosis of the skin is net-like or marbled and caused by stasis in the

capillaries furthest from their arterial supply: at the periphery of the

inverted cone supplied by a dermal arteriole (see Fig. 2.1). ‘Cutis marmorata’

is the name given to the mottling of the skin seen in many normal children. It

is physiological and disappears on warming, whereas true livedo reticularis

remains.

The causes of livedo reticularis are listed in Table 11.3. Livedo vasculitis and cutaneous polyarteritis are forms of vasculitis associated with livedo reticularis .

Antiphospholipid syndrome

Some patients with an apparently idiopathic livedo reticularis develop progressive disease in their peri-pheral, cerebral, coronary and renal arteries. Others, usually women, have multiple arterial or venous thrombo-embolic episodes accompanying livedo reticularis. Recurrent spontaneous abortions and intrauterine fetal growth retardation are also features. Prolongation of the activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT) and the presence of antiphospholipid antibodies (either anticardiolipin antibody or lupus anticoagulant, or both) help to identify this syndrome. Systemic lupus erythematosus should be excluded .

Erythema ab igne

This

appearance is also determined by the underlying vascular network. Its

reticulate pigmented erythema, with variable scaling, is caused by damage from

long-term exposure to local heatausually from an open fire, hot water bottle or

heating pad. If on one side of the leg, it gives a clue to the side of the fire

on which granny likes to sit (Fig. 11.2). The condition is com-mon in northern

Europe (‘tinker’s tartan’), but rare in the USA, where central heating is the

rule.

Flushing

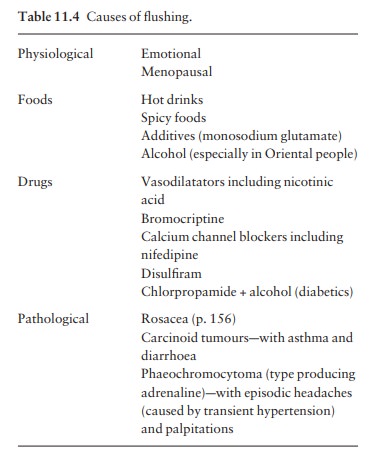

This

transient vasodilatation of the face may spread to the neck, upper chest and,

more rarely, other parts of the body. There is no sharp distinction between

flushing and blushing apart from the emotional pro-vocation of the latter. The

mechanism varies with the many causes that are listed in Table 11.4. Paroxysmal

flushing (‘hot flushes’), common at the menopause, is associated with the

pulsatile release of luteinizing hormone from the pituitary, as a consequence

of low circulating oestrogens and failure of normal negative feedback. However,

luteinizing hormone itself cannot

be

responsible for flushing as this can occur after hypophysectomy. It is possible

that menopausal flush-ing is mediated by central mechanisms involving

encephalins. Hot flushes can usually be helped by oestrogen replacement.

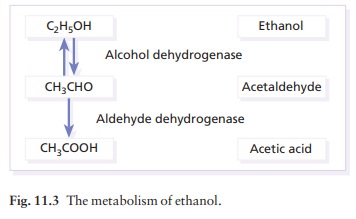

Alcohol-induced

flushing is most commonly seen in oriental people. Ethanol is broken down to

acetalde-hyde by alcohol dehydrogenase and acetaldehyde is metabolized to

acetic acid by aldehyde dehydrogenase (Fig. 11.3). Acetaldehyde accumulation is

in part responsible for flushing. Oriental people not only may have a

high-activity variant of alcohol dehydrogenase but also defective aldehyde

dehydrogenase. Disulfuram (Antabuse) and, to a lesser extent, chlorpropamide

inhibit aldehyde dehydrogenase so that some indi-viduals taking these drugs may

flush.

Related Topics