Chapter: Clinical Dermatology: Disorders of blood vessels and lymphatics

Venous hypertension, the gravitational syndrome and venous leg ulceration

Venous

hypertension, the gravitational syndrome and venous leg ulceration

Ulcers

of the lower leg, secondary to venous hyperten-sion, have an estimated

prevalence of around 1%, are more common in women than in men, and account for

some 85% of all leg ulcers seen in the UK and USA.

Cause

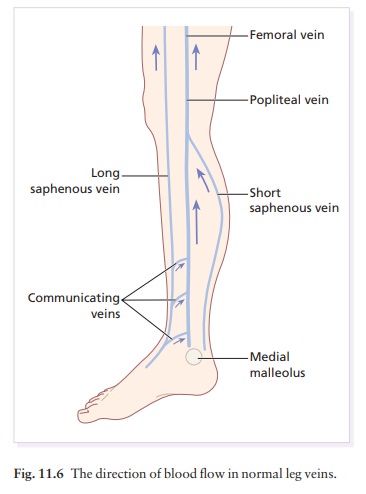

Satisfactory

venous drainage of the leg requires three sets of veins: deep veins surrounded by muscles; superficial

veins; and the veins connecting these togetherathe perforating or communicating

veins (Fig. 11.6). When the leg muscles contract, blood in the deep veins is

squeezed back, against gravity, to the heart (the calf muscle pump); reflux is

prevented by valves. When the muscles relax, with the help of gravity, blood

from the superficial veins passes into the deep veins via the communicating

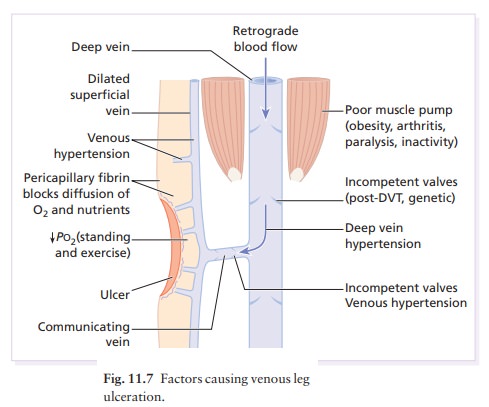

vessels. If the valves in the deep and communicating veins are incompetent, the

calf muscle pump now pushes blood into the super-ficial veins, where the

pressure remains high (‘venous hypertension’) instead of dropping during

exercise. This persisting venous hypertension enlarges the cap-illary bed;

white cells accumulate here and are then activated (by hypoxic endothelial

cells), releasing oxygen free radicals and other toxic products which cause local

tissue destruction and ulceration. The increased venous pressure also forces

fibrinogen and α2-macroglobulin out through the capillary walls;

thesemacromolecules trap growth and repair factors so that minor traumatic

wounds cannot be repaired and an ulcer develops. Patients with these changes

develop lipodermatosclerosis and have a

high serum fibrinogen and reduced blood fibrinolytic activity. Figure 11.7

shows the factors causing venous ulceration.

Clinical features

Venous

hypertension is heralded by a feeling of heavi-ness in the legs and by pitting

oedema. Other signs include:

1 red

or bluish discoloration;

2 loss of

hair;

3 brown

pigmentation (mainly haemosiderin fromthe breakdown of extravasated red blood

cells) and scattered petechiae;

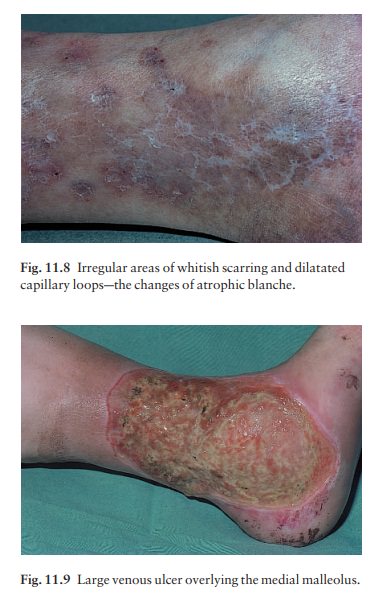

4 atrophie

blanche (ivory white scarring withdilatated capillary loops; Fig. 11.8); and

5 induration,

caused by fibrosis and oedema of thedermis and subcutisasometimes called

‘lipoder-matosclerosis’.

Ulceration

is most common near the medial malleo-lus (Fig. 11.9). In contrast to arterial

ulcers, which are usually deep and round, with a punched out appearance, venous

ulcers are often large but shallow, with prominent granulation tissue in their

bases. Incompetent perforating branches (blowouts) between the superficial and

deep veins are best felt with the patient standing. Under favourable conditions

the exudative phase gives way to a granulating and healing phase, signalled by

a blurring of the ulcer mar-gin, ingrowth of skin from it, and the appearance

of scattered small grey epithelial islands over the base. Prolonged ulceration,

with lipodermatosclerosis, gives the leg the look of an inverted champagne

bottle.

Complications

Bacterial superinfection is inevitable in a longstanding ulcer, but needs systemic antibiotics only if there is pyrexia, a purulent discharge, rapid extension or an increase in pain, cellulitis, lymphangitis or septicaemia.

Eczema is common around venous ulcers. Allergic

contact dermatitis is a common

com-plication and should be suspected if the rash worsens, itches or fails to

improve with local treatment. Lanolin, parabens (a preservative) and neomycin

are the most common culprits.

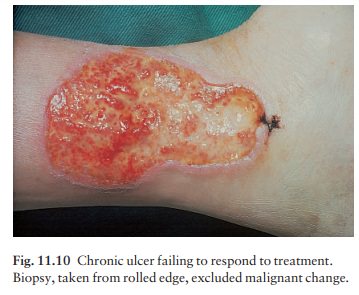

Malignant

change can occur. If an ulcer has a hyper-plastic base or a rolled edge, biopsy

may be needed to rule out a squamous cell carcinoma (Fig. 11.10).

Differential diagnosis

The

main causes of leg ulceration are given in Table 11.7. The most important

differences between venous and other leg ulcers are the following.

Atherosclerotic.

These ulcers are more common onthe toes, dorsum of foot, heel, calf and shin,

and are unrelated to perforating veins. Their edges are often sharply defined,

their outline may be polycyclic and the ulcers may be deep and gangrenous.

Islands of intact skin are characteristically seen within the ulcer.

Claudication may be present and peripheral pulses absent.

Vasculitic.

These ulcers start as painful palpable pur-puric lesions, turning into small

punched-out ulcers.

The

involvement of larger vessels is heralded by painful nodules that may ulcerate.

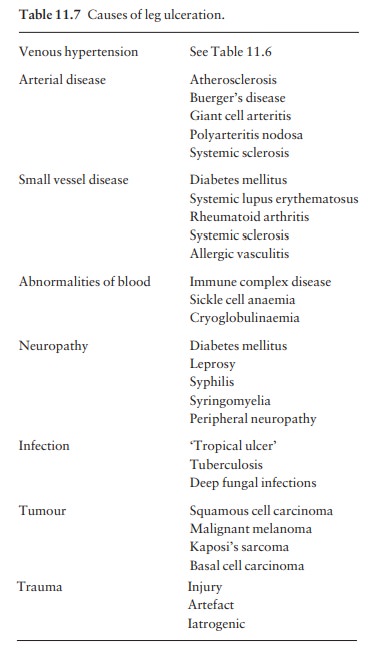

The intractable deep sharply demarcated ulcers of rheumatoid arthritis are

caused by an underlying vasculitis (Fig. 11.11).

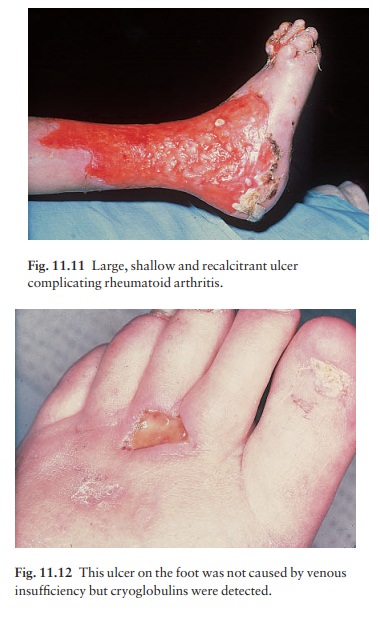

Thrombotic

ulcers. Skin infarction (Fig. 11.12), lead-ing to ulceration, may

be caused by embolism or by the increased coagulability of polycythaemia or

cryoglobulinaemia.

Infective

ulcers. Infection is now a rare cause of legulcers in the UK but

ulcers caused by tuberculosis, leprosy, atypical mycobacteria, diphtheria and

deep fungal infections, such as sporotrichosis or chro-moblastomycosis, are

still seen in the tropics.

Panniculitic

ulcers. These may appear at odd sites,such as the thighs, buttocks

or backs of the calves. The most common types of panniculitis that ulcerate are

lupus panniculitis, pancreatic panniculitis and erythema induratum.

Malignant

ulcers. Those caused by a squamous cellcarcinoma are the most common, but both malignant

melanomas and basal cell

carcino-mas can present as flat lesions,

which expand, crust and ulcerate. Furthermore, squamous cell carci-noma can

arise in any longstanding ulcer, whatever its cause.

Pyoderma

gangrenosum. These large andrapidly spreading ulcers may be circular or

polycyclic, and have a blue, indurated, undermined or pustular margin. Pyoderma

gangrenosum may complicate rheumatoid arthritis, Crohn’s disease, ulcerative

co-litis or blood dyscrasias.

Investigations

Most

chronic leg ulcers are venous, but other causes should be considered if the

signs are atypical. In patients with venous ulcers, a search for contributory

factors, such as obesity, peripheral artery disease, cardiac failure or

arthritis, is always worthwhile. Investigations should include the following.

•

Urine test for sugar.

•

Full blood count to detect anaemia,

which will delay healing.

•

Swabbing for pathogens (see

Bacterial superinfec-tion above).

•

Venography, colour flow duplex

scanning and the measurement of ambulatory venous pressure help to detect

surgically remediable causes of venous incompetence.

•

Doppler ultrasound may help to

assess arterial cir-culation when atherosclerosis is likely. It seldom helps if

the dorsalis pedis or posterior tibial pulses can easily be felt. If the

maximal systolic ankle pressure divided by the systolic brachial pressure

(‘ankle brachial pres-sure index’) is greater than 0.8, the ulcer is unlikely

to be caused by arterial disease.

Cardiac

evaluation for congestive failure.

Venous

ulcers will not heal if the leg remains swollen and the patient chair-bound.

Pressure bandages take priority over other measures but not for

atheroscle-rotic ulcers with an already precarious arterial supply. A common error

is to use local treatment that is too elaborate. As a last resort, admission to

hospital for elevation and intensive treatment may be needed, but the results

are not encouraging; patients may stay in the ward for many months only to have

their appar-ently well-healed ulcers break down rapidly when they go home.

The

list of therapies is extensive. They can be divided into the following

categories: physical, local, oral and surgical.

Physical measures

Compression bandages and stockings

Compression

bandaging, with the compression gradu-ated so that it is greatest at the ankle

and least at the top of the bandage, is vital for most venous ulcers; it

reduces oedema and aids venous return. The ban-dages are applied over the ulcer

dressing, from the forefoot to just below the knee. Self-adhesive ban-dages

(e.g. Secure Forte and Coban) are convenient and have largely replaced

elasticated bandages. Bandages stay on for 2–7 days at a time and are left on

at night. One four-layer compression bandaging system includes a layer of

orthopaedic wool (Velband), a standard crepe, an elasticated bandage (e.g.

Elset and Litepress) and an elasticated cohesive bandage (e.g. Secure Forte and

Coban): it requires changing only once a week and is very effective. The

combined four layers give a 40-mmHg compression at the ankle. Once an ulcer has

healed, a graduated compression stocking (e.g. Duomed, Medi Strumpf, or Venosan

2502/2003 (UK) or Jobst or Teds (USA)) from toes to knee (or preferably thigh),

should be prescribed, preferably at pressures of at least 35 mmHg. A foam or

felt pad may be worn under the stockings to pro-tect vulnerable areas against

minor trauma. The stocking should be put on before rising from bed. Care must

be taken with all forms of compression to ensure that the arterial supply is

satisfactory and not compromised.

Elevation of the affected limb

Preferably

above the hips, this aids venous drainage, decreases oedema and raises oxygen

tension in the limb. Patients should rest with their bodies horizontal and their

legs up for at least 2 h every afternoon. The foot of the bed should be raised

by at least 15 cm ; it is not enough just to put a pillow under the feet.

Walking

Walking,

in moderation, is beneficial, but prolonged standing or sitting with dependent

legs is not.

Physiotherapy

Some

physiotherapists are good at persuading venous ulcers to heal. Their secret

lies in a combination of the following: leg exercises, elevation, gentle

massage, ultrasound treatment to the skin around the ulcers, oedema pumps and graduated

compression bandaging.

Diet

Many

patients are obese and should lose weight.

Local therapy

Remember

that many ulcers will heal with no treat-ment at all but, if their blood flow

is compromised, they will not heal despite meticulous care.

Local

therapy should be chosen to:

•

control or absorb the exudates;

•

reduce the pain;

•

control the odour;

•

protect the surrounding skin;

•

remove surface debris;

•

promote re-epithelialization; and

•

make optimal use of nursing time.

There

are many preparations to choose from; those we have found most useful are

listed in Formulary 1.

Clean

ulcers (Fig. 11.13)

Dressings

need be changed only once or twice a week, keeping the ulcer moist. Paraffin

tulle dressings, plain or impregnated with 0.5% chlorhexidine, 0.25% silver

proteinate in compound calamine cream spread on a non-stick dressing, 1% silver

sulphadiazine cream, and simple zinc and castor oil ointment, are all helpful

and easy to apply. The area should be cleaned gently with arachis oil, 5%

hydrogen peroxide or saline before the next dressing is applied. Sometimes

immersing the whole ulcer in a tub of warm water helps to loosen or dissolve

adherent crusts. The pro-longed use of antiseptics may be harmful.

Many

dressings have absorbent and protective pro-perties. These include Granuflex

and DuoDERM Extra Thin (which have the advant-age of sticking to the

surrounding skin), Geliperm, Kaltostat and Sorbsan in the UK and Duoderm,

Opsite and Tegaderm in the USA. Actisorb (UK) is a useful charcoal dressing

that absorbs exudate and minimizes odour. Ointments containing recombinant

human platelet growth factor may aid revascularization.

Medicated bandages based on zinc paste, with ichthammol, or with calamine and clioquinol, are useful when there is much surround-ing eczema, and can be used for all types of ulcers, even infected exuding ones. The bandage is applied in strips from the foot to below the knee. Worsening of eczema under a medicated bandage may signal the development of allergic contact dermatitis to a component of the paste, most often parabens (a pre-servative) or cetostearyl alcohols.

Infected

ulcers (Fig. 11.14)

These

have to be cleaned and dressed more often than clean ones, sometimes even twice

daily. Useful pre-parations include 0.5% silver nitrate, 0.25% sodium

hypochlorite, 0.25% acetic acid, potassium perman-ganate (1 in 10 000 dilution)

and 5% hydrogen per-oxide, all made up in aqueous solution, and applied as

compresses with or without occlusion. Helpful creams and lotions include 1.5%

hydrogen peroxide, 20% benzoyl peroxide, 1% silver sulphadiazine, 10%

povidone-iodine. The main function of dextran polymer beads, and starch

poly-mer beads within cadexomer iodine, is to absorb exudate. Although

antibiotic tulles are easy to apply and are well tolerated, they should not be

used for long periods as they can induce bacterial resistance and sensitize.

Resistance is not such a problem with povidone-iodine, and a readily applied

non-adherent dressing impregnated with this antiseptic may be useful.

Surrounding eczema is helped by weak or moderate strength local steroids, which

must never be put on the ulcer itself. Lassar’s paste, zinc cream or paste

bandages are suitable alternatives.

Oral treatment

The

following may be helpful.

Diuretics.

Pressure bandaging is more important asthe oedema associated with venous

ulceration is largely mechanical. Diuretics will combat the oedema of cardiac

failure.

Analgesics. Adequate analgesia is important.

Aspirinmay not be well tolerated by the elderly. Paracetamol (not available in

the USA), or acetaminophen is often adequate but dihydrocodeine may be

required. Ana-lgesia may be needed only when the dressing is changed.

Antibiotics. Ulcers need not be ‘sterilized’ by

local orsystemic antibiotics. Short courses of systemic anti-biotics should be

reserved for spreading infections (see under Complications above) but are

sometimes tried for pain or even odour. Bacteriological guidance is needed and

the drugs used include erythromycin and flucloxacillin (streptococcal or

staphylococcal cellulitis), metronidazole (Bacteroides

infection) and ciprofloxacin (Pseudomonas aeruginosa

infection). Bacterial infection may prejudice the outcome of skin grafting.

Ferrous

sulphate and folic acid. For anaemia.

Zinc

sulphate. May help to promote healing, espe-cially if the plasma

zinc level is low.

Oxypentifylline

(pentoxyfylline) is fibrinolytic, in-creases the

deformability of red and white blood cells, decreases blood viscosity and

diminishes platelet adhes-iveness. It may speed the healing of venous ulcers if

used with compression bandages.

Stanozolol.

This anabolic steroid may not heal anexisting ulcer more quickly, but may

prevent ulcera-tion in lipodermatosclerosis and may protect against

recurrences. The manufacturer’s advice on contrain-dications, e.g. prostatic

cancer and abnormal liver function, and on monitoring treatment must not be

overlooked.

Oxerutins.

These may help the oedema and symptomsof venous hypertension and are said to

reduce leakage from capillaries by acting on the endothelial cells.

Surgery

Autologous

pinch, split-thickness or mesh grafts have a place. Lyophilized pig dermis, and

synthetic films similar to skin, may also be tried. Sheets of human epidermis

grown in tissue culture can be purchased and placed on granulating wound beds.

Even if grafts do not take, they may stimulate wound healing and relieve pain.

In general, grafts work best on clean ulcers.

Venous

surgery on younger patients with varicose veins may prevent recurrences, if the

deep veins are competent. Patients with atherosclerotic ulcers should see a

vascular surgeon for assessment. Some blockages are surgically remediable.

Related Topics