Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: The Psychiatric Interview: Settings and Techniques

Dimensions of Interviewing Techniques

Dimensions of Interviewing Techniques

Although many systems have been suggested for

classifying in-terview techniques (Elliott et

al., 1987), it is convenient to think about four major dimensions of

interviewing style: degree of di-rectiveness, degree of emotional support,

degree of fact versus feeling orientation and degree of feedback to the

patient. The interviewer must seek a balance among these dimensions to best

cover the needed topics, build rapport, and arrive at a plan of treatment.

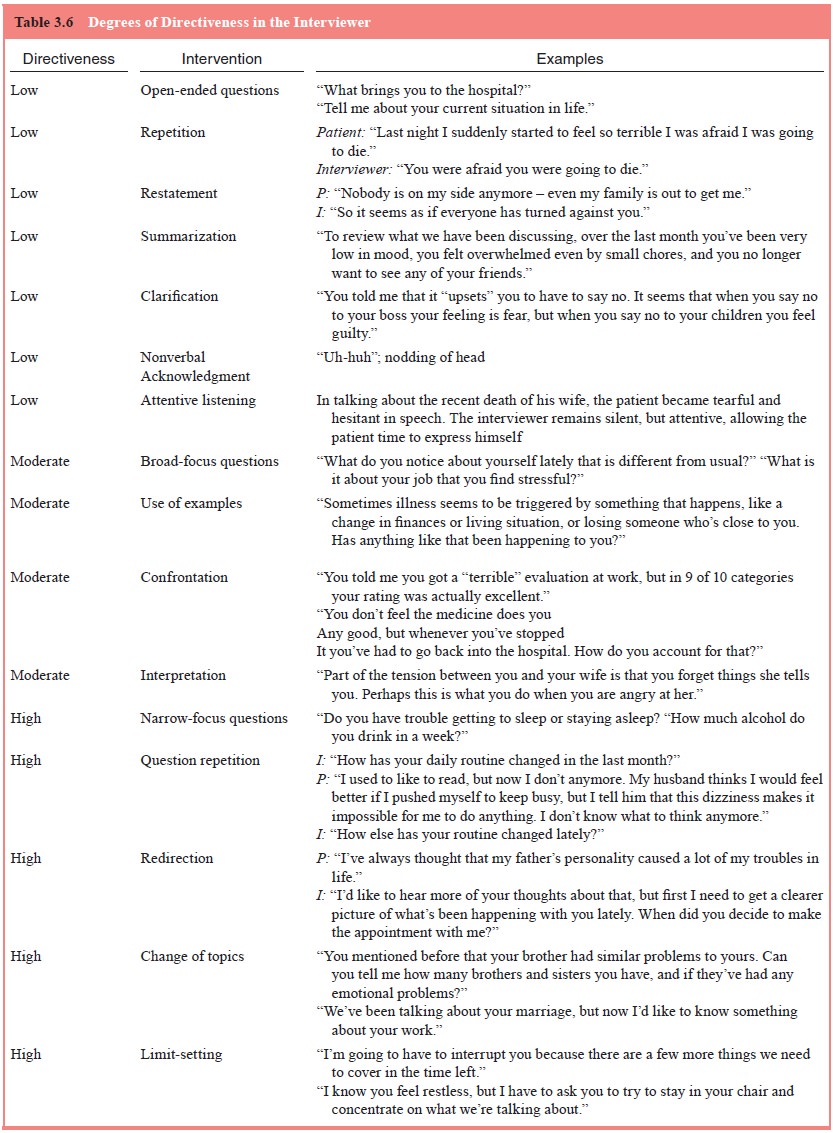

Directiveness

Directiveness in the interview ensures that the

necessary areas of information are covered and supplies whatever cognitive

sup-port the patient needs in discussing them. Table 3.6 lists inter-ventions

which are low, moderate and high in directiveness.

Low-directive interventions request information in

the broadest, most open-ended way and do not go beyond the mate-rial supplied

by the patient. Moderately directive interventions are narrower in focus and

may extend beyond what the patient himself/herself has said. For example, confrontation

makes the patient aware of paradoxes or inconsistencies in the material and

requests him/her to resolve them; interpretation requests the pa-tient to

consider explanations or connections that had not previ-ously occurred to

him/her. Highly directive interventions aim to focus and restrict the patient’s

content or behavior. Such inter-ventions include yes–no or symptom-checklist

type questions and requests for the patient to modify behaviors that impede the

progress of the interview.

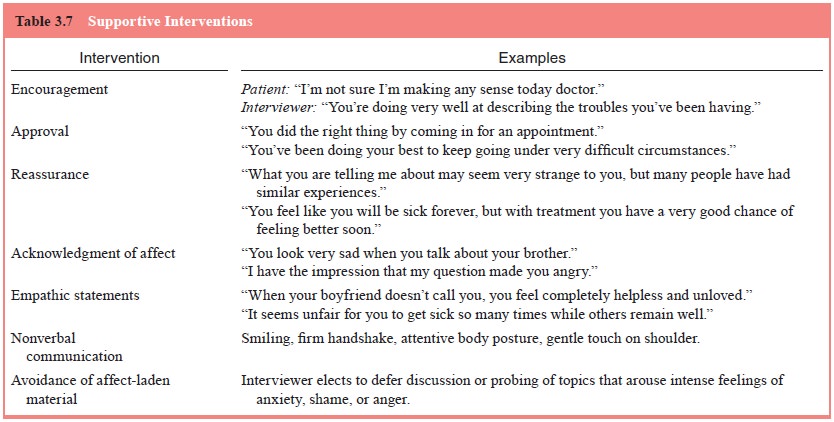

Supportiveness

Patients vary considerably in the degree of

emotional and cogni-tive support they need in the interview. Table 3.7 lists

examples of emotionally supportive interventions. Each such intervention

supports the patient’s sense of security and self-esteem. While some patients

may come to the interview feeling safe and con-fident, others have considerable

anxiety about being criticized, ridiculed, rejected, taken advantage of, or

attacked (literally so in the case of some psychotic patients).

Overt manifestations of insecurity range widely,

from fearful demeanor and tremulousness to requests for reassur-ance to haughty

contemptuousness. The interview’s task is to identify such anxiety when it

arises and respond in a manner.

that conveys empathic understanding, acceptance and

positive regard.

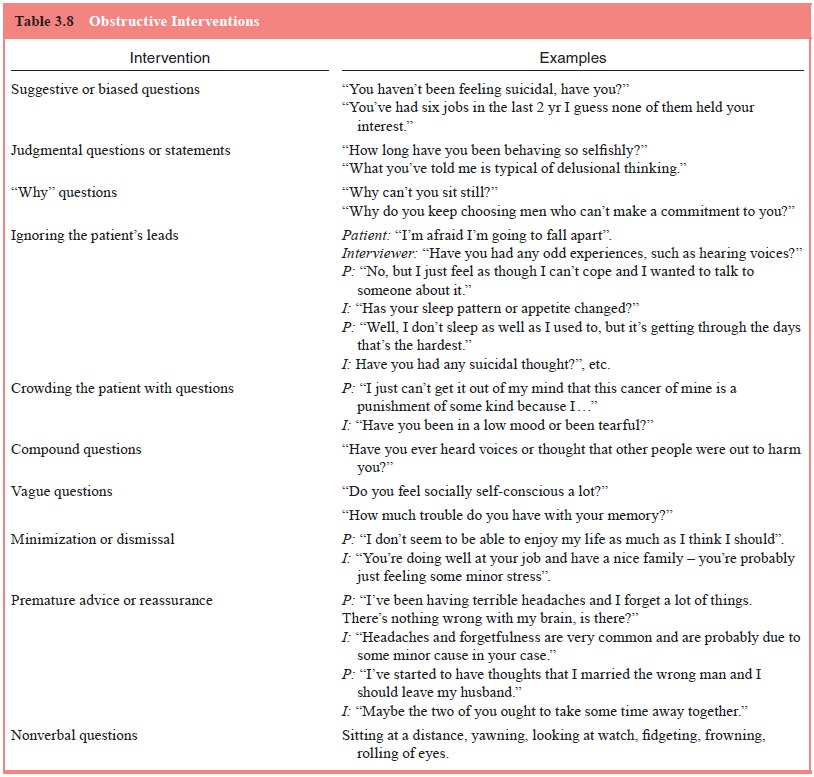

Obstructive interventions are one which (usually

unin-tentionally) impede the flow of information and diminish rap-port. Table

3.8 lists common examples of such interventions. Compound or vague questions

are often confusing to the pa-tient and may produce ambiguous or unclear

answers. Biased or judgmental questions suggest what answer the interviewer

wants to hear or that he/she does not approve of what the pa-tient is saying.

“Why” questions often sound critical or invite rationalizations. “How”

questions better serve the purposes of the interview (“How did you come to

change jobs?” rather than “Why did you change jobs?”). Other interventions are

obstructive because they disregard the patient’s feeling state or what he/she

is trying to say. Paradoxically, this may in-clude premature reassurance or

advice. When given before the interviewer has explored and understood the

issue, this has the effect of cutting off feelings and coming to a premature closure.

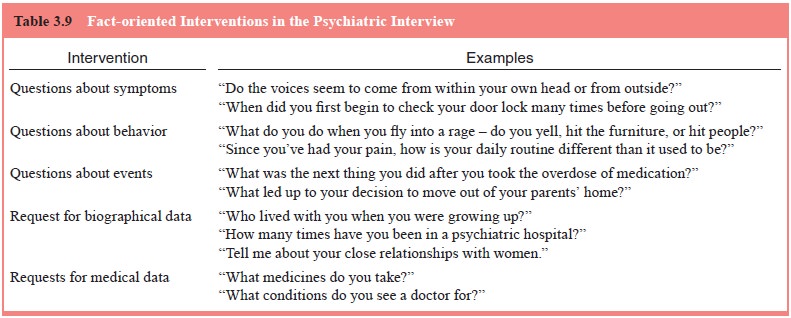

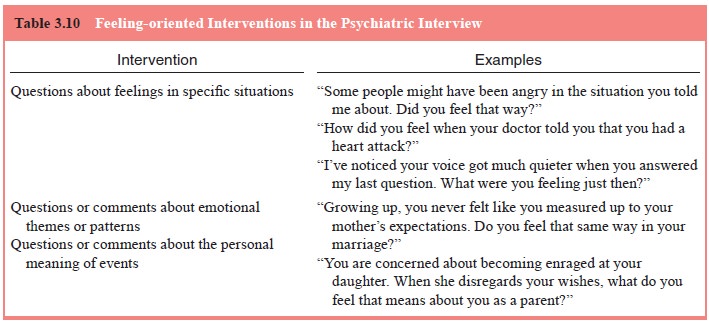

Fact Versus Feeling Orientation

Interviews differ in the degree to which they focus

on factual– objective versus feeling–meaning oriented material. Tables 3.9 and

3.10 provide examples of interventions of both types. The interviewer must

determine what the salient issues are in a given case and develop the focus

accordingly. For example, at one extreme, the principal task in assessing a

cyclically occurring mood disorder might be to delineate precisely the

symptoms, time course and treatment response of the illness. At the other end

of the spectrum might be a patient with a circumscribed dif-ficulty in living,

such as the inability to achieve an intimate, last-ing love relationship. In

such a case, the interviewer may focus not only on the facts of the patient’s

interactions with others but also on the feelings, fantasies and thoughts

associated with such relationships.

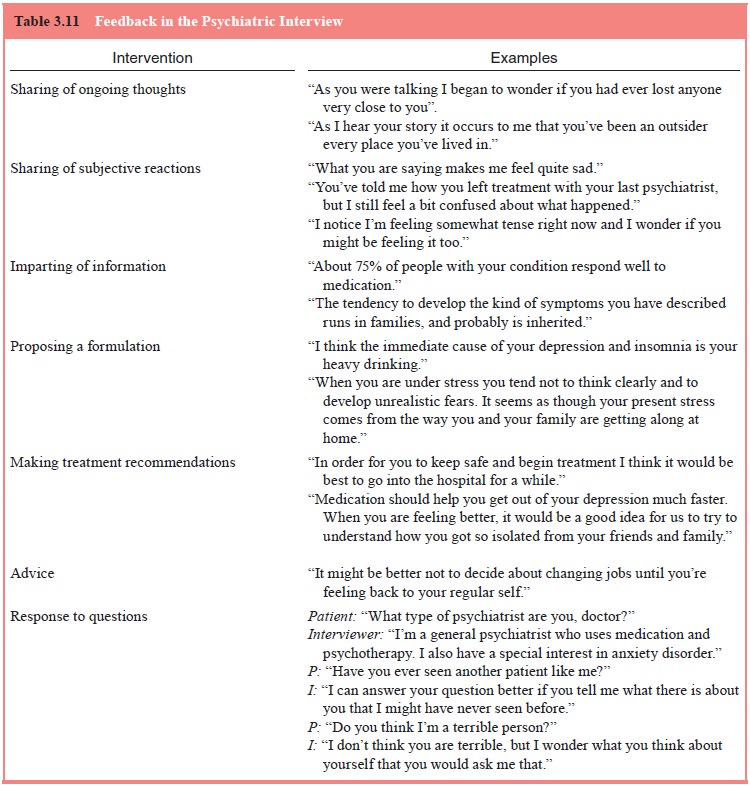

Feedback

Interviews differ in how much the interviewer

conveys to the patient of his/her own thoughts, feelings, conclusions and

rec-ommendations. Table 3.11 presents common types of feedback from the

interviewer. Judicious statements about the interview-er’s ongoing thoughts and

feelings can be used to pose ques-tions or make clarifications or

interpretations while enhanc-ing rapport and trust. Communication of factual

information, formulations of the problem and treatment recommendations are the

foundations of joint treatment planning with the patient. Responding to

questions and giving advice may serve an edu-cational purpose as well as

enhancing the alliance. When re-sponding to requests for advice or information,

the interviewer must first take care to be sure of what is being asked, and for

what reason.

There is little systematic data on the superiority

of one clinical interviewing style over another, but what there are suggest

that many styles can be used effectively. Rutter and his colleagues have

investigated this question in a series of natural-istic and experimental

studies of interviews of parents in a child psychiatry clinic (Rutter et al., 1981; Cox et al., 1981, 1988). The major findings of these studies are:

· Active,

structured techniques are no better than nondirec-tive styles in eliciting

positive findings (i.e., areas of pathol-ogy). However, active techniques are

better in eliciting more detailed and thorough information in areas where

pathol-ogy is found and are also better at delineating areas without pathology.

· An

active, fact-gathering style does not prevent the inter-viewer from effectively

eliciting emotional reactions from informants.

· Use of open questions, direct requests for feelings, interpreta-tions of feelings, and expressions of sympathy are associated with greater expression of emotions by informants.

· Less

activity on the interviewer’s part is associated with more informant

talkativeness and spontaneous emotional expres-sion. Less directive techniques

also tend to produce more emotional responses at times when they are not

specifically requested. Conversely, more active styles of asking about feelings

may be more effective for informants who are low in spontaneous emotional expression.

·

In summary, techniques which actively elicit both

facts and emotions are likely to produce the richest, most detailed da-tabase.

When skillfully used, these do not impair the doctor– patient relationship.

Related Topics