Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: Physician–Patient Relationship

Physician–Patient Relationship

Physician–Patient Relationship

For centuries, healers had little understanding of

disease and lacked the technologies we now know are necessary for the treatment

and cure of many diseases. Physicians had few medications, and surgery was only

a last resort. In fact, the most important tool for healing was the

relationship between the physician and the patient. Interpersonal relationships

have a powerful influence on both morbidity and mortality (House et al., 1988). Social connectedness

enhances health in both direct and indirect ways: directly regulating many

biological functions, decreasing anxiety, providing opportunities for new

information, and fostering alternative behaviors (Hofer, 1984). We know little

about the basic mechanisms by which interpersonal relationships, and the

physician–patient relationship in particular, operate (Ursano and Fullerton

1991). However, clinical wisdom holds that both the reality-based elements of

the physician–patient relationship – in modern times referred to as the working

alliance or the therapeutic alliance (Zetzel, 1956; Greenson, 1965) – and the

fantasy-based elements of that relationship affect the patient’s pain,

suffering and recovery from illness.

Physicians learned through trial and error to

interact with their patients in ways that relieved pain and promoted health

(Frank, 1971). Often the physician’s only interventions were reassuring

patients, providing knowledge about the patient’s disease, accept-ing the

patient’s feelings of distress as normal, and maximizing the patient’s hope for

the future. Although these interventions, based on wisdom and intuition, are no

longer the only tools available to the physician, they continue to be an

important part of the physician’s and particularly the psychiatrist’s

therapeutic armamentarium.

Such nonspecific aspects of cure are often thought

to be mystical or mysterious. In fact, in biological studies they are

rec-ognized as the placebo effect. Oddly, these effects of interper-sonal

relationships are both one of the prized and one of the most denigrated aspects

of all of medicine. Yet, as clinicians, we all strive to alleviate our

patients’ pain and suffering and return them to health as soon as possible with

whatever tools may help. Many well-designed studies show that 20 to 30% of

subjects respond to the placebo condition. Recent studies show that analgesic

pla-cebo has similar neural mechanisms to opioid analgesia (Petrovic et al., 2002). The problem with placebos

is not whether they work but that we

do not understand how they work and, therefore, we do not have control over

their effects. As a physician, one strives to maximize one’s interpersonal

healing effects and, in this way as well as with other healing tools, increase

the chances of our patients’ relief from pain and of recovery.

The physician–patient relationship includes

specific roles and motivations. These form the core ingredients of the

healingprocess. In its most generic form the physician–patient relation-ship is

defined by the coming together of an expert and a help seeker to identify,

understand and solve the problems of the help seeker. The help seeker (in

modern terms, the patient) is moti-vated by the desire and hope for assistance

and relief from pain (Sullivan, 1954). A physician is required to have a

genuine interest in people and a desire to help (Lidz, 1983). Simply stated,

“the se-cret of the care of the patient is in caring for the patient” (Peabody,

1927). Caring about and paying attention to a patient’s suffering can yield

remarkable therapeutic dividends. More than one attend-ing physician has been

reminded of this when a patient deferred making a treatment decision until he

or she was able to consult with “my doctor”, who turned out to be the medical

student.

In today’s technology-driven medicine, the

importance and complexity of the physician–patient interaction are often

over-looked. The amount of information the medical student or resident must

learn frequently takes precedence over learning the fine points of helping the

patient relax sufficiently to provide a thorough his-tory or to allow the

physician to palpate a painful abdomen. Talk-ing with patients and

understanding the intricacies of the physi-cian–patient relationship may be

given little formal attention in the medical school curriculum. Even so, medical

students, residents and staff physicians recognize, often with awe, the skill

of the sen-ior physician who uncovers the lost piece of history, motivates the

patient who had given up hope, or is able to talk to the distressed family

without increasing their sense of hopelessness or fear.

The relationship between the physician and the

patient is es-sential to the healing of many patients, perhaps particularly so

for many psychiatric patients. The physician who can skillfully recog-nize the

patient’s half-hidden comment that he or she has not been taking the prescribed

medication, perhaps hidden because of feel-ings of shame, anger, or denial, is

better able to ensure long-term compliance with medication as well as to

motivate the patient to stay in treatment. Regardless of the type of treatment

– medication, biofeedback, hospitalization, psychotherapy, or the rearrangement

of the demands and responsibilities in the patient’s life – the rela-tionship

with the physician is critical to therapeutic outcome.

Modern medicine emphasizes a specific role for the

physi-cian in the relationship with the patient. In many Western coun-tries,

the patient comes for help with a specific problem, the doctor’s office staff

secures permission from a third party payer for the doctor to conduct a

particular treatment, a prescribed intervention, which will take a specified

amount of time. Dec-ades ago, when the doctor was neighbor, advisor and friend

to the patient and routinely invited to important family events inthe patient’s

life such as weddings of children, and when doctors routinely cared for more

than one generation of the same family, the physician typically assumed that he

or she would be a source of strength and assistance to the patient throughout

the cycle of life. This meant more than curing a specific disease or relieving

a specific pain.

While today’s patients may not consciously expect

that the physician’s influence and healing powers will take many forms in a

complex interpersonal relationship, human nature is still the same, and

patients still want from their doctors many nonspe-cific forms of emotional

support which can promote a sense of well-being and better health. Though

modern doctors may feel a great deal of time pressure to see many patients each

day and to focus narrowly their healing efforts, the physician must also be

sensitive to the many needs of patients, who believe that the physician is

possessed of wisdom and understanding. Sensitivity to such desires and needs

will promote effective medical care in all specialties, with all patients. A

view that such patients are unusually needy and demanding will not serve the

cause of ef-fective medical care.

Finally, in today’s mobile and geographically

evermore united world, the importance of recognizing the needs of patients from

parts of the world other than that of the physician’s is a chal-lenge to the

practitioner. The physician must be open to the limita-tions of his or her

knowledge of the expectations, beliefs and likely behavior of patients from

different cultures, nations, religions, and ethnic and socioeconomic

backgrounds. The physician must rec-ognize this challenge and one hopes,

embrace it with enthusiasm. It can make the practice of medicine a more

exciting experience.

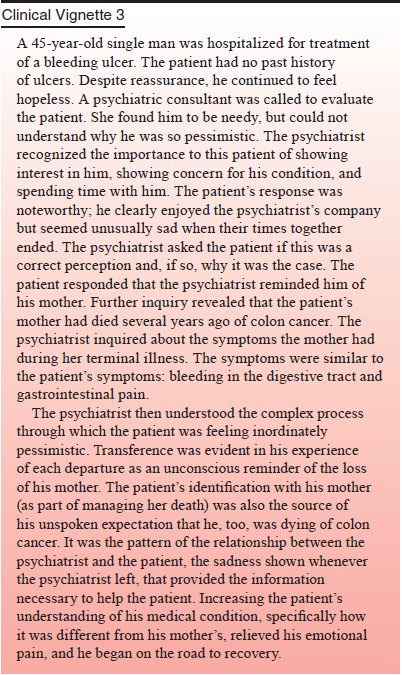

The physician–patient relationship is also a source

of information for the physician. The way the patient relates to the physician

can help the physician understand the problems the patient is experiencing in

her or his interpersonal relation-ships. The nature of the physician–patient

relationship can also provide information about relationships in the patient’s

child-hood family, in which interpersonal patterns are first learned. With this

information, the physician can better understand the patient’s experience,

promote cooperation between the patient and those who care for her or him, and

teach the patient new behavioral strategies in an empathic manner,

understanding the patient’s subjective perspective, that is, feelings, thoughts

and behaviors.

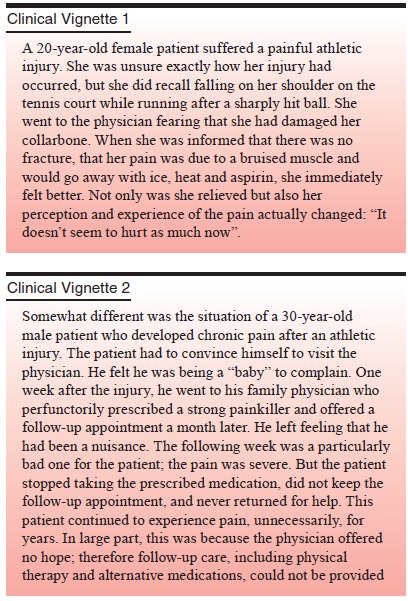

These clinical vignettes illustrate that the

physician–patient relationship is composed of both the reality-based component

(the working alliance or therapeutic alliance) and the fantasy-based component

(the transference) derived from the patient’s patterns of interpersonal

behavior learned in childhood. Either or both of these may maximize or limit

the patient’s sense of reassurance, available information, feelings of comfort

and sense of hope (Meissner, 1996). In this way, the nonspecific curative as-pects

of the physician–patient relationship may be enhanced or diminished.

Related Topics