Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: The Psychiatric Interview: Settings and Techniques

Database Components

Database Components

Identifying Data

This information establishes the patient’s identity, especially for the purpose of obtaining past history from other contacts, when necessary, as well as to fix his/her position in society. The pa-tient’s name should be recorded, along with any nickname or al-ternative names he/she may have been known by in the past. This is important for women who might have been treated previously under a maiden name, or a patient who has had legal entangle-ments and so has adopted aliases.

Date of birth, or at least age, and race are other

essen-tial parts of every person’s database. A number of different

classifications for race exist, as well as different terms and con-troversies

(Porter, 1993). In the USA and Canada, the categories of white, black (or

African-American), Asian, Native American, and others are generally accepted.

The additional modifier of ethnicity, especially Hispanic/nonHispanic, is

becoming more widely used. If a patient is a member of a particular subculture

based on ethnicity, country of origin, or religious affiliation, it may be

noted here.

A traditional part of the identifying data is a

reference to the patient’s civil status: single, married, separated, divorced,

or widowed. The evolution of relationship patterns over the last two decades,

with less frequent formalization of rela-tionships, has made classification

more difficult (Ishii-Kuntz and Tallman, 1991), especially in the case of

homosexual pa-tients, whose relationships are not legally recognized in most

jurisdictions.

The patient’s social security number (or other

national ID number) can be a very useful bit of data when seeking informa-tion

from other institutions.

In most cases, it is assumed that the informant

(supplier of the history) is the patient. If other sources are used, and

espe-cially if the patient is not the primary informant, this should be noted

at the beginning of the database.

Chief Complaint

The chief complaint is the patient’s responses to

the question, “What brings you to see me/to the hospital today?” or some

vari-ant. It is usually quoted verbatim, placed within quotation marks, and

should be no more than one or two sentences.

Even if the patient is very disorganized or

hostile, quoting his response can give an immediate sense of where the patient

is as the interview begins. If the patient responds with an exple-tive, or a

totally irrelevant remark, the reader of the database is immediately informed

about how the rest of the information may be distorted. In such cases, or if

the patient gives no response, a brief statement of how the patient came to be

evaluated should be made and enclosed in parentheses.

History of the Present Illness

Minimum Essential Database

The present illness history should begin with a

brief description of the major symptoms which brought the patient to

psychiatric attention. The most troubling symptoms should be detailed

ini-tially; later a more thorough review will be stated. As a minimum, the

approximate time since the patient was last at his baseline level of

functioning, and in what way he is different from that now, should be

described, and any known stressors, the sequence of symptom development, and

the beneficial or deleterious effects of interventions included.

How far back in a patient’s history to go,

especially when he has chronic psychiatric illness, is sometimes problematic.

In patients who have required repeated hospitalization, a summary of events

since last discharge (if within 6 months) or last stable baseline is indicated.

It is rare that more than 6 months of his-tory be included in the history of

the present illness, and detailed history is more commonly given on the past

month.

Expanded Database

A more expanded description of the history of the

present illness would include events in a patient’s life at the onset of

symptoms, as well as exactly how the symptoms have affected the patient’s

occupational functioning and important relationships. Any concurrent medical

illness symptoms, medication usage (and particularly changes), alterations in

the sleep–wake cycle, appe-tite disturbances and eating patterns should be

noted; significant negative findings should also be remarked upon.

Past Psychiatric History

Minimum Essential Database

Most of the major psychiatric illnesses are chronic

in nature. For this reason, often patients have had previous episodes of

illness with or without treatment. New onset of symptoms, without any previous

psychiatric history, becomes increasingly important with advancing age in terms

of diagnostic categories to be con-sidered. At a minimum, the presence or

absence of past psychi-atric symptomatology should be recorded, along with

psychiatric interventions taken and the result of such interventions. An

ex-plicit statement about past suicide and homicide attempts should be

included.

How far

back in a patient’s history to go, especially when he has chronic psychiatric

illness, is sometimes problematic. In patients who have required repeated

hospitalization, a summary of events since last discharge (if within 6 months)

or last stable baseline is indicated. It is rare that more than 6 months of

his-tory be included in the history of the present illness, and detailed

history is more commonly given on the past month.

Past Medical History

Minimum Essential Database

In any clinical assessment, it is important to know

how a patient’s general health status has been. In particular, any current

medical illness and treatment should be noted (Slaby and Andrew, 1987), along

with any major past illness requiring hospitalization. Pre-vious endocrine or

neurological illness are of particular perti-nence (Flomenbaum and Altman,

1985)

Expanded Database

An expanded database could well include significant

childhood illnesses, how these were handled by the patient and his fam-ily, and

therefore the degree to which the patient was able to develop a sense of

comfort and security about his physical well-being. Illnesses later in life

should be assessed for the degree of regression produced. The amount of time a

patient has had to take off work, how well he/she was able to follow a regimen

of medical care, his/her relationship with the family physician or treating

specialist can all be useful in predicting future re-sponse to treatment. A

careful past medical history can also at times bring to light a suicide

attempt, substance abuse, or dangerously careless behavior, which might not be

obtained any other way.

Family History

Minimum Essential Database

Given the evidence for familial, genetic factors in

so many psychiatric conditions, noting the presence of mental illness in

biological relatives of the patient is a necessary part of any database (Hammen

et al., 1987). It is important to

specify during questioning the degree of family to be considered – usually to

the second degree: aunts, uncles, cousins and grandparents, as well as parents,

siblings and children.

Expanded Database

A history of familial medical illness is a useful

part of an ex-panded database. A genogram (pedigree), including known fam-ily

members with dates and causes of death and other known chronic illnesses is

helpful. Questioning about causes of death will also occasionally bring out

hidden psychiatric illness, for example, sudden, unexpected deaths which were

likely suicides or illness secondary to substance abuse.

Personal History

Minimum Essential Database

Recording the story of a person’s life can be a

daunting under-taking and is often where a database can expand dramatically. As

a minimum, this part of the history should include where a patient was born and

raised, and in what circumstances – intact family, number of siblings and

degree of material comfort. Note how far the patient went in school, how he/she

did there, and what his/her occupational functioning has been. If he/she is not

working, why not? Has the patient ever been involved in crimi-nal activity, and

with what consequences? Has the patient ever married or been involved in a

committed relationship? Are there any children? What is his/her current source

of support? Does he/she live alone or with someone? Has he/she ever used

alcohol or other drugs to excess, and is there current use? Has he/she ever

been physically or sexually abused or been the victim of some other trauma?

Expanded Database

An expanded database can include a great deal of

material begin-ning even prior to the patient’s conception. What follows is an

outline of the kind of data which may be gathered, along with an organizational

framework.

Family of Origin

Were parents married or in committed relationships?

Personality and significant events in life of

mother, father, or other significant caregiver.

Siblings: how many? their ages, significant life

events, person-ality, relationship to patient.

Who else shared the household with the family?

Prenatal and Perinatal

Was the pregnancy planned? Quality of prenatal

care; mother’s and father’s response to pregnancy.

Illness, medication or substance abuse, smoking,

trauma dur-ing pregnancy; labor – induced or spontaneous?

Weeks gestation, difficulty of delivery, vaginal or

Caesarean section.

Presence of jaundice at birth, birth weight, Apgar

score.

Baby went home with mother or stayed on in

hospital.

Early

Childhood

Developmental milestones: smiling, sitting,

standing, walk-ing, talking, type of feeding – food allergies or intolerance.

Consistency of caregiving: interruptions by

illness, birth of siblings.

Reaction to weaning, toilet-training, maternal

separation. Earliest memories: problematic behavior (tantrums, bedwetting,

hair-pulling or nail-biting).

Temperament (shy, overactive, outgoing, fussy).

Sleep problems: insomnia, nightmares, enuresis,

parasomnias.

Later

Childhood

Early school experiences: evidence of separation

anxiety.

Behavioral problems at home or school: firesetting,

bedwetting, aggressive toward others, cruelty to animals, nightmares.

Developmental milestones: learning to read, write.

Relationships with other children and family: any

loss or trauma.

Reaction to illness.

Adolescence

School performance: ever in special classes?

Athletic abilities and participation in sports.

Evidence of gender identity concerns: overly

“feminine” or “masculine” in appearance/behavior, or perception by peers.

Ever run away? Able to be left alone and assume

responsibility. Age onset of puberty (menarche or nocturnal emissions),

reaction to puberty.

Identity

Sexual preference and gender identity, religious

affiliation (same as parents?).

Career goals: ethnic identification.

Sexual

History

Early sexual teaching: earliest sexual experiences,

experi-ence of being sexually abused, attitudes toward sexual behavior.

Dating history, precautions taken to prevent

sexually transmit-ted diseases and/or pregnancy.

Episodes of impotence and reaction.

Masturbating patterns and fantasies.

Preoccupation with particular sexual practices,

current sex-ual functioning, length of significant relationships, ages of

partners.

Age at which left home, level of educational

attainments. Employment history, relationships with supervisors and peers at

work, reasons for job change.

History of significant relationships including

duration, typical roles in relationships, patterns of conflict: mari-tal

history, legal entanglements and criminal history, both covert and detected,

ever victim or perpetrator of violence.

Major medical illness as adult.

Participation in community affairs.

Financial status: own or rent home, stability of

living situation. Ever on disability or public assistance?

Current family structure, reaction to losses of

missing mem-bers (parents, siblings), if applicable.

Substance abuse history.

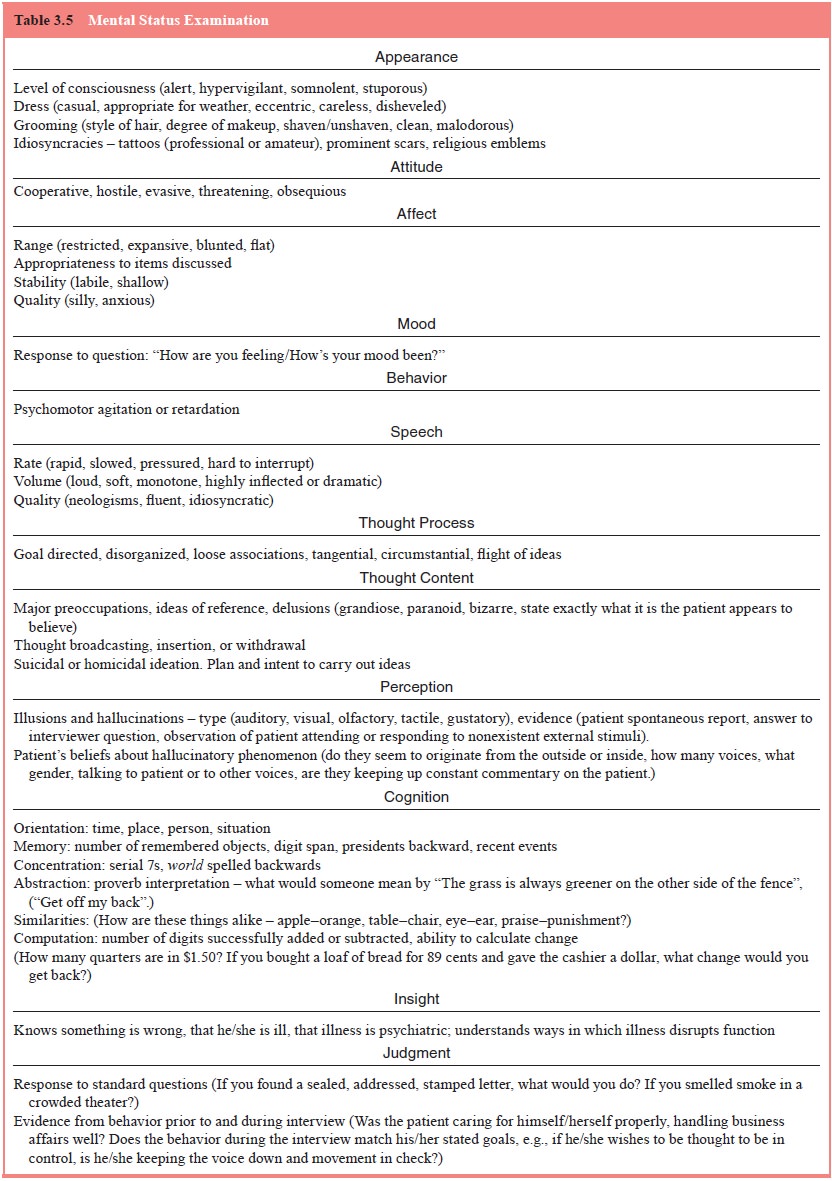

Mental Status Examination

It can be helpful to conceptualize the recording of

the Men-tal Status Examination as a progression. One begins with a snapshot:

what can be gained from a cursory visual exam, without any movement or

interaction – appearance and affect. Next, motion is added: behavior. Then

comes sound: the pa-tient’s speech, though initially only as sound. The ideas

being expressed come next: the thought process and content, per-ception,

cognition, insight, and judgment. Table 3.5 gives a summary of areas to be

commented on, along with common terms.

At every level of the Mental Status Examination,

prefer-ence should be given for explicit description over jargon. Stating that

a patient is delusional is less helpful than describing him as believing that

his neighbors are pumping poisonous gases into his bedroom while he sleeps.

Related Topics