Chapter: Modern Medical Toxicology: General Principles: General Management of Poisoning

Decontamination - General Management of Poisoning

Decontamination

EYE

Irrigate

copiously for at least 15 to 20 minutes with normal saline or water. Do not use

acid or alkaline irrigating solutions. As a first-aid measure at home, a victim

of chemical burns should be instructed to place his face under running water or

in a shower while holding the eyelids open. During transportation to hospital

the face should be immersed in a basin of water (while ensuring that the patient

does not inhale water).

SKIN

Cutaneous absorption is a common

occurrence especially with reference to industrial and agricultural substances

such as phenol, hydrocyanic acid, aniline, organic metallic compounds,

phosphorus, and most of the pesticides. The following measures can be

undertaken to minimise absorption*—

■■ Exposed

persons should rinse with cold water and then wash thoroughly with a

non-germicidal soap. Repeat the rinse with cold water.

■■ Corroded

areas should be irrigated copiously with water or saline for at least 15

minutes. Do not use “neutralising solutions”.

■■ Remove

all contaminated clothes. It is preferable to strip the patient completely and

provide fresh clothes, or cover with clean bedsheet.

■■ Some

chemical exposures require special treatment :

· Phenolic burns should be treated by

application of polyethylene.

· Phosphorus burns should be treated

with copper sulfate solution.

· For hydrofluoric acid burns, use of

intradermal or intra-arterial calcium gluconate decreases tissue necrosis.

· For tar, bitumen, or asphalt burns,

first irrigate the affected skin with cold water and then clean and apply

solvents such as kerosene, petrol, ethanol, or acetone. However, since these

substances can not only be locally cytotoxic, but also be absorbed through the

skin, it is preferable to use mineral oil, petrolatum, or antibacte-rial

ointments in a petrolatum base. Prolonged irrigating applications may be

required.

GUT

The various methods of poison

removal from the gastrointes-tinal tract include:

■■ Emesis

■■ Gastric

lavage

■■ Catharsis

■■ Activated

charcoal

■■Whole bowel irrigation

Emesis

The

only recommended method of inducing a poisoned patient to vomit is

administration of syrup of ipecacuanha

(or ipecac). However, the initial

enthusiasm associated with the use of ipecac in the 1960s and 1970s in western

countries has declined substantially in recent years owing to doubts being

raised as to its actual efficacy and safety. The current consensus is thatsyrup of ipecac must NOT be used, except

in justifiable circumstances.

Syrup of Ipecac

·

Source—Root of a small shrub (Cephaelis ipecacuanha or C. acuminata) which grows well in West

Bengal (Fig 3.1).

·

Active principles: Cephaeline,

emetine, and traces of psychotrine.

·

Indications: Conscious and alert

poisoned patient who has ingested a poison not more than 4 to 6 hours earlier.

·

Mode of action:

o Local

activation of peripheral sensory receptors in the gastrointestinal tract.

o Central

stimulation of the chemoreceptor trigger zone with subsequent activation of the

central vomiting centre.

·

Dose:

o

30 ml (adult), or 15 ml (child), followed by 8 to 16 ounces,

i.e. 250 to 500 ml approximately, of water.

o

The patient should be sitting up.

o

If vomiting does not occur within 30 minutes, repeat the

same dose once more. If there is still no effect, perform stomach wash to

remove not only the ingested poison but also the ipecac consumed. However the therapeutic doses of ipecac

recommended above are not really harmful.

■■ Contra-indications:

·

Relative

:

––

Very young (less than 1 year), or very old patient –– Pregnancy

–– Heart disease

–– Bleeding diathesis

–– Ingestion of cardiotoxic poison

–– Time lapse of more than 6 to 8 hours

·

Absolute

:

––

Convulsions, or ingestion of a convulsant poison –– Impaired gag reflex

–– Coma

––

Foreign body ingestion –– Corrosive ingestion

––

Ingestion of petroleum distillates, or those drugs which cause altered mental

status (phenothiazines, antihistamines, opiates, ethanol, benzodiazepines,

tricyclics).

––

All poisons which are themselves emetic in nature

·

Complications:

Cardiotoxicity (bradycardia, atrial

fibrillation, myocar- ditis).

Aspiration pneumonia.

Oesophageal mucosal or Mallory Weiss tears

(due toprotracted vomiting).

Other Emetics

The only other acceptable method of

inducing emesis that is advocated involves the use of apomorphine. Given subcu-taneously, it causes vomiting within 3 to

5 minutes by acting directly on the chemoreceptor trigger zone. The recommended

dose is 6 mg (adult), and 1 to 2 mg (child). Since apomorphine is a respiratory

depressant it is contraindicated in all situations where there is likelihood of

CNS depression.

In some cases, stimulation of the posterior pharynx with a finger or a blunt

object may induce vomiting by provoking the gag reflex. Unfortunately, such

mechanically induced evacua-tion is often unsuccessful and incomplete, with

mean volume of vomitus about one third of that obtained by the other two

methods.

Obsolete Emetics

The

use of warm saline or mustard water as an emetic is not only

dangerous (resulting often in severe hypernatraemia), but also impractical

since many patients, especially children refuse (fortunately) to drink this

type of concoction and much valuable time is lost coaxing them to do so. One

tablespoon of salt contains at least 250 mEq of sodium, and if absorbed can

raise the serum level by 25 mEq/L in for instance, a 3-year old child.* It is

high time that the use of salt water as an emetic be deleted once and for all

from every first-aid chart or manual on poisoning.

Copper sulfate induces

emesis more often than commonsalt, but significant elevations of serum copper

can occur leading to renal and hepatic damage. It is also a gastrointestinal

corrosive.

Zinc sulfate is

similar in toxicity to copper sulfate, and hasin addition a very narrow margin

of safety.

Gastric Lavage (Stomach Wash)

The

American Academy of Clinical Toxicology (AACT), and the European Association of

Poison Centres and Clinical Toxicology (EAPCCT) have prepared a draft of a

position paper directed to the use of gastric lavage, which suggests that

gastric lavage should not be employed routinely in the management of poisoned

patients. There is no certain evidence that its use improves outcome, while the

fact that it can cause significant morbidity (and sometimes mortality) is

indisputable. Lavage should be considered only if a patient has ingested a

life-threatening amount of a poison and presents to the hospital within 1 to 2

hours of ingestion.

But

in India, very often caution is thrown to the wind and the average physician in

an average hospital embarks on gastric lavage with gusto the moment a poisoned

patient is brought in. A sad commentary on the existing lack of awareness and a

reluctance to change old convictions in spite of mounting evidence against the

routine employment of such “established procedures”.

■■ Indications—

·

Gastric lavage is recommended mainly for patients whohave

ingested a life-threatening dose, orWho exhibit significant morbidity and

present within1 to 2 hours of ingestion. Lavage beyond this periodmay be

appropriate only in the presence of gastricconcretions, delayed gastric

emptying, or sustainedrelease preparations. Some authorities still

recommendlavage upto 6 to 12 hours post-ingestion in the case ofsalicylates,

tricyclics, carbamazepine, and barbiturates

·

Precautions—

o

Never undertake lavage in a patient who has ingested a

non-toxic agent, or a non-toxic amount of a toxic agent.

o

Never use lavage as a deterrent to subsequent inges- tions.

Such a notion is barbaric, besides being incorrect.

·

Contraindications—

o

Relative: Haemorrhagic diathesis,

oesophageal varices, recent surgery, advanced pregnancy, ingestion of alkali,

coma.

o

Absolute: Marked hypothermia, prior

significant vomiting, unprotected airway in coma, and ingestion of acid or

convulsant or petroleum distillate, and sharp substances.

·

Procedure—

o Explain the exact procedure to the

patient and obtain his consent. If refused, it is better not to undertake

lavage because it will amount to an assault, besides increasing the risk of

complications due to active non-co-operation.

o Endotracheal

intubation must be done prior to lavage in the comatose patient.

o Place

the patient head down on his left lateral side (20o tilt

on the table).

o Mark

the length of tube to be inserted (50 cm for an adult, 25 cm for a child).*\

o The

ideal tube for lavage is the lavacuator

(clear plastic or gastric hose).

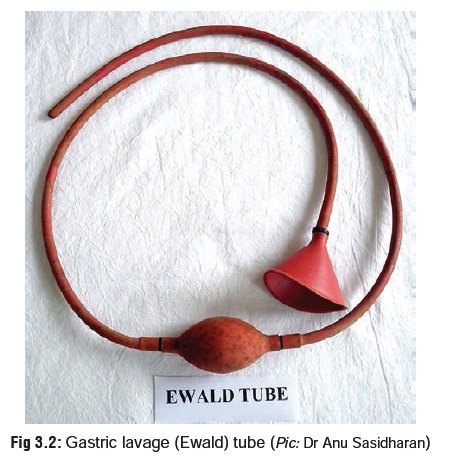

o In India however, the Ewald tube is most often used which is a soft rubber tube with a funnel at one end (Fig 3.2). Whatever tube is used, make sure that the inner diameter corresponds to at least 36 to 40 French size.** A nasogastric tube used for gastric aspiration is inadequate and should never be used. In a child, the diameter should be at least 22 to 28 French, (Ryle’s tube may be sufficient – Fig 3.3).

o The

preferred route of insertion is oral. Passing the tube nasally can damage the

nasal mucosa considerably and lead to severe epistaxis. Lubricate the inserting

end of the tube with vaseline or glycerine, and pass it to the desired extent.

Use a mouth gag so that the patient will not bite on the tube.

o Once

the tube has been inserted, its position should be checked either by air

insufflation while listening over the stomach, or by aspiration with pH testing

of the aspirate, (acidic if properly positioned).

o Lavage

is carried out using small aliquots (quantities) of liquid. In an adult, 200 to

300 ml aliquots of warm (38o C) saline

or plain water are used. In a child, 10 to 15 ml/kg body weight of warm saline

is used each time. Water should preferably be avoided in young children because

of the risk of inducing hyponatraemia and water intoxication. It is advisable

to hold back the first aliquot of washing for chemical analysis.

o In

certain specific types of poisoning, special solutions may be used in place of

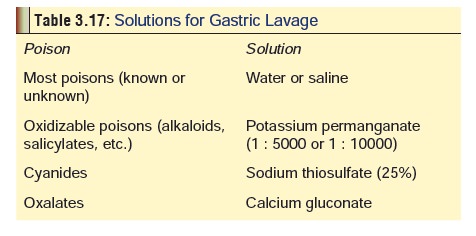

water or saline (Table 3.17).

o Lavage

should be continued until no further particulate matter is seen, and the

efferent lavage solution is clear. At the end of lavage, pour a slurry of

activated charcoal in water (1 gm/kg), and an appropriate dose of an ionic

cathartic into the stomach, and then remove the tube.

Complications –

·

Aspiration pneumonia.

·

Laryngospasm.

·

Sinus bradycardia and ST elevation

on the ECG.

·

Perforation of stomach or oesophagus

(rare).

Catharsis

Catharsis is a very appropriate term when used in connection with poisoning, since it means purification. It is achieved by purging the gastrointestinal tract (particularly the bowel) of all poisonous material.

The

two main groups of cathartics* used in toxicology include

·

Ionic

or Saline:

––

These cathartics alter physico-chemical forces within the intestinal lumen

leading to osmotic retention of fluid which activates motility reflexes and

enhances expulsion. However, excessive doses of magnesium-based cathartics can

lead to hypermagnesaemia which is a serious complication.

––

The doses of recommended cathartics are as follows:

-- Magnesium citrate: 4 ml/kg

--

Magnesium sulfate: 30 gm (250 mg/kg in a child)

-- Sodium sulfate: 30 gm (250 mg/kg in a child).

·

Saccharides:

––

Sorbitol (D-glucitol) is the cathartic of choice in adults because of better

efficacy than saline cathartics, but must not be used as far as possible in

young children owing to risk of fluid and electrolyte imbalance (especially

hypernatraemia).

––

It occurs naturally in many ripe fruits and is prepared industrially from

glucose, retaining about 60% of its sweetness. Sorbitol is used as a sweetener

in some medicinal syrups, and the danger of complications is enhanced in

overdose with such medications when sorbitol is used as a cathartic during

treatment.

–– Dose of sorbitol: 50 ml of 70% solution

(adult).

·

Efficacy of catharsis:

While

cathartics do reduce the transit time of drugs in the gastrointestinal tract,

there is no real evidence that it improves morbidity or mortality in cases of

poisoning.

·

Contraindications:

–– Corrosives

––

Existing electrolyte imbalance

––

Paralytic ileus

–– Severe diarrhoea

––

Recent bowel surgery

––

Abdominal trauma

––

Renal failure.

Oil

based cathartics should never be used in poisoning since they increase the risk

of lipoid pneumonia, increase the absorption of fat soluble poisons, and

inactivate medicinal charcoal’s effects when administered along with them. The

last mentioned reason also applies to conventional laxatives, and hence they

are also not recommended in poisoning.

Activated (Medicinal) Charcoal

A

number of studies have documented clearly the efficacy of activated charcoal as

the sole decontamination measure in ingested poisoning, while emesis and lavage

are increasingly being associated with relative futility.

Activated

charcoal is a fine, black, odourless, tasteless powder (Fig 3.4) made from burning wood, coconut shell, bone, sucrose, or

rice starch, followed by treatment with an activating agent (steam, carbon

dioxide, etc.). The resulting particles are extremely small, but have an

extremely large surface area. Each gram of activated charcoal works out to a

surface area of 1000 square metres.

·

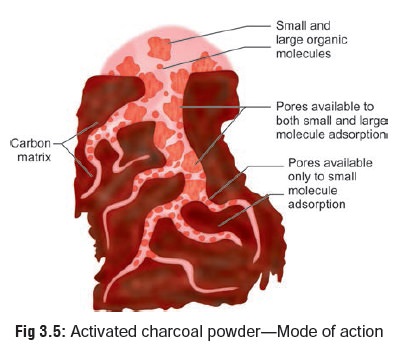

Mode of action—

Decreases

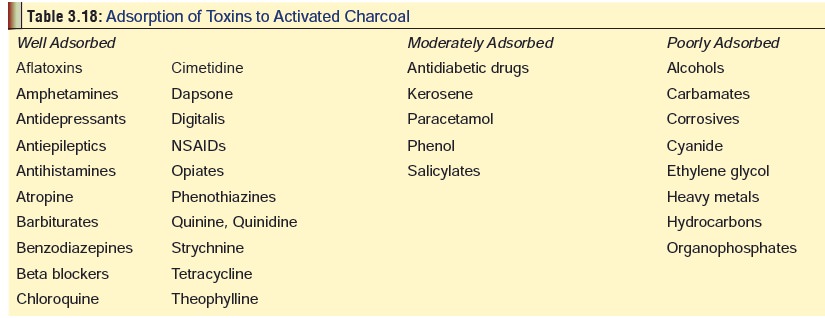

the absorption of various poisons by adsorbing them on to its surface (Fig 3.5). Activated charcoal is

effec-tive to varying extent, depending on the nature of substance ingested (Table 3.18).

·

Dose—

1 gm/kg body

weight (usually 50 to 100 gm in an adult, 10 to 30 gm in a child).

·

Procedure—

·

Activated charcoal is most effective

when administered within one hour of ingestion. Administration in the prehospital setting has the potential to

significantly decrease the time from toxin ingestion to activated charcoal

administration, although it has not been shown to affect outcome.

·

Add four to eight times the quantity

of water to the calculated dose of activated charcoal, and mix to produce a

slurry or suspension. This is administered to the patient after emesis or

lavage, or as sole inter- vention. The slurry should be shaken well before

administration.

Multiple-dose Activated Charcoal: The use of repeated doses

(amounting to 150 to 200 gm of activated charcoal) has been demonstrated to be

very effective in the elimination of certain drugs such as theophylline,

phenobarbitone, quinine, digitoxin, phenylbutazone, salicylates and

carbamazepine. The actual dose of activated charcoal for multiple dosing has

varied consider- ably in the available medical literature, ranging from 0.25 to

0.5 gm/kg every 1 to 6 hours, to 20 to 60 gm for adults every 1, 2, 4, or 6

hours. The total dose administered is more important than frequency of

administration.

·

Disadvantages—

o Unpleasant

taste*

o Provocation

of vomiting

o Pulmonary

aspiration

o Intestinal

obstruction (especially with multiple-dose activated charcoal).

·

Contraindications—

o Absent

bowel sounds or proven ileus

o Small

bowel obstruction

o Caustic

ingestion

o Ingestion

of petroleum distillates.

Whole Bowel Irrigation (Whole Gut Lavage)

This

is a method that is being increasingly recommended for late presenting

overdoses when several hours have elapsed since ingestion. It involves the

instillation of large volumes of a suit-able solution into the stomach in a

nasogastric tube over a period of 2 to 6 hours producing voluminous diarrhoea.

Previously, saline was recommended for the procedure but it resulted in

electrolyte and fluid imbalance. Today, special solutions are used such as PEG-ELS ( i.e. polyethylene glycol and

electro-lytes lavage solution combined together, which is an isosmolar

electrolyte solution), and PEG-3350

(high molecular weight polyethylene glycol) which are safe and efficacious,

without producing any significant changes in serum electrolytes, serum

osmolality, body weight, or haematocrit.

·

Indications—

·

Ingestion of large amounts of toxic

drugs in patients presenting late ( > 4 hours post-exposure)

·

Overdose with sustained-release

preparations.

·

Ingestion of substances not adsorbed

by activated char- coal, particularly heavy metals.

·

Ingestion of foreign bodies such as

miniature disc batteries (button cells), cocaine filled packets (body packer syndrome),** etc.

·

Ingestion of slowly dissolving

substances: iron tablets, paint chips, bezoars, concretions, etc.

·

Procedure—

·

Insert a nasogastric tube into the

stomach and instil one of the recommended solutions at room temperature, at a

rate of 2 litres per hour in adults, and 0.5 litre per hour in children. The

patient should preferably be seated in a commode. The use of metoclopramide IV,

(10 mg in adults, 0.1 to 0.3 mg/ kg in children) can minimise the incidence of

vomiting. The procedure should be continued until the rectal effluent is clear,

which usually occurs in about 2 to 6 hours.

·

Complications—

o Vomiting

o Abdominal

distension and cramps

o Anal

irritation.

·

Contraindications—

o Gastrointestinal

pathology such as obstruction, ileus, haemorrhage, or perforation.

Related Topics