Chapter: Essentials of Anatomy and Physiology: Blood Vessels and Circulation

Control of Blood Flow in Tissues

CONTROL OF BLOOD FLOW IN TISSUES

Blood flow provided to the tissues by the circulatory system is highly controlled and matched closely to the metabolic needs of tissues. Mechanisms that control blood flow through tissues are classified as (1) local control or (2) nervous and hormonal control.

Local Control Of Blood Flow

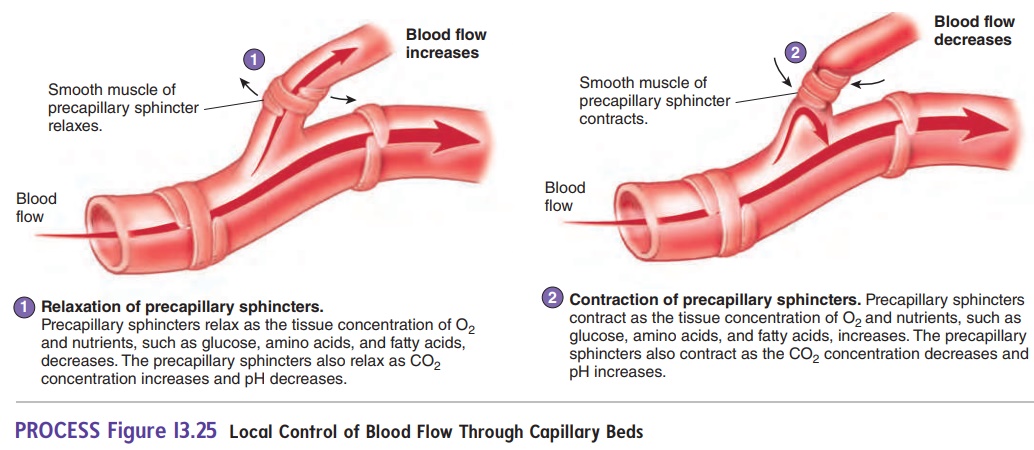

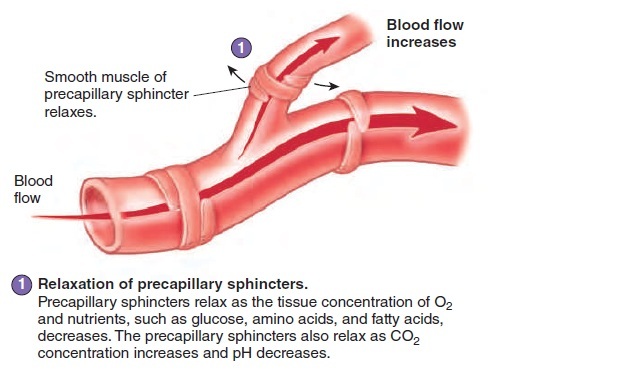

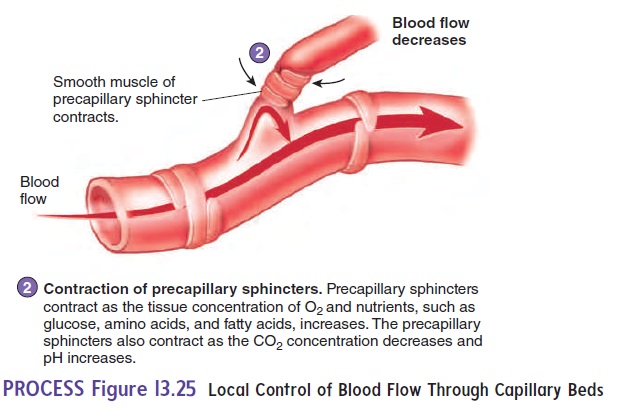

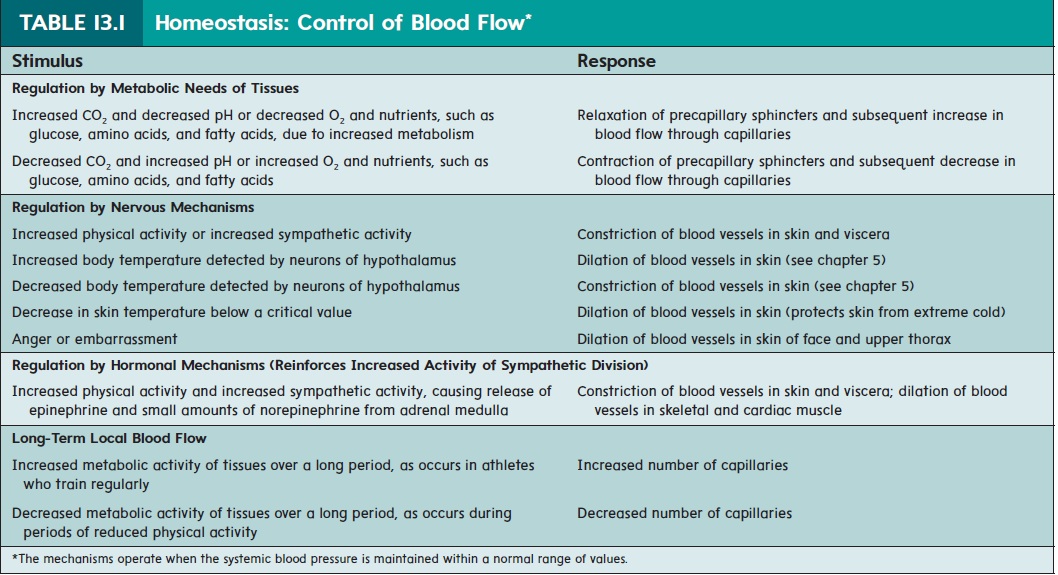

Local control of blood flow is achieved by the periodic relaxation and contraction of the precapillary sphincters. When the sphincters relax, blood flow through the capillaries increases. When the sphincters contract, blood flow through the capillaries decreases. The precapillary sphincters are controlled by the metabolic needs of the tissues. For example, blood flow increases when by-products ofmetabolism buildup in tissue spaces. During exercise, the metabolic needs of skeletal muscle increase dramatically, and the by-products of metabolism are produced more rapidly. The precapillary sphincters relax, increasing blood flow through the capillaries.

Other factors that control blood flow through the capillaries are the tissue concentrations of O2 and nutrients, such as glucose, amino acids, and fatty acids (figure 13.25 and table 13.1). Blood flow increases when O2 levels decrease or, to a lesser degree, when glucose, amino acids, fatty acids, and other nutrients decrease. An increase in CO2 or a decrease in pH also causes the precapillary sphincters to relax, thereby increasing blood flow.

In addition to the control of blood flow through existing capil-laries, if the metabolic activity of a tissue increases often, additional capillaries gradually grow into the area. The additional capillaries allow local blood flow to increase to a level that matches the meta-bolic needs of the tissue. For example, the density of capillaries in the well-trained skeletal muscles of athletes is greater than that in skeletal muscles on a typical nonathlete (table 13.1).

Nervous And Hormonal Control Of Blood Flow

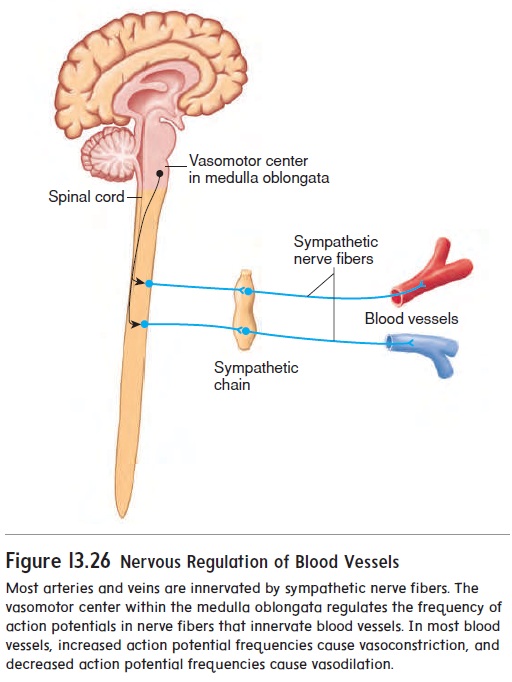

Nervous control of blood flow is carried out primarily through the sympathetic division of the autonomic nervous system. Sympathetic nerve fibers innervate most blood vessels of the body, except the capillaries and precapillary sphincters, which have no nerve supply (figure 13.26).

An area of the lower pons and upper medulla oblongata, called the vasomotor center, continually transmits a low fre-quency of action potentials to the sympathetic nerve fibers. As a consequence, the peripheral blood vessels are continually in a partially constricted state, a condition called vasomotor (v̄a -s̄o - m̄o ′ ter) tone. An increase in vasomotor tone causes blood vessels to constrict further and blood pressure to increase. A decrease in vasomotor tone causes blood vessels to dilate and blood pressure to decrease. Nervous control of blood vessel diameter is an impor-tant way that blood pressure is regulated.

Nervous control of blood vessels also causes blood to be shunted from one large area of the body to another. For example, nervous control of blood vessels during exercise increases vaso-motor tone in the viscera and skin and reduces vasomotor tone in exercising skeletal muscles. As a result, blood flow to the viscera and skin decreases, and blood flow to skeletal muscle increases. Nervous control of blood vessels during exercise and dilation of precapillary sphincters as muscle activity increases together increase blood flow through exercising skeletal muscle several-fold (table 13.1).

The sympathetic division also regulates hormonal control of blood flow through the release of epinephrine and norepinephrine from the adrenal medulla. These hormones are transported in the blood to all parts of the body. In most blood vessels, these hormones cause constriction, which reduces blood flow. But in some tissues, such as skeletal muscle and cardiac muscle, these hormones cause the blood vessels to dilate, increasing blood flow.

Related Topics