Chapter: Introduction to the Design and Analysis of Algorithms : Brute Force and Exhaustive Search

Closest-Pair and Convex-Hull Problems by Brute Force

Closest-Pair

and Convex-Hull Problems by Brute Force

In this

section, we consider a straightforward approach to two well-known prob-lems

dealing with a finite set of points in the plane. These problems, aside from

their theoretical interest, arise in two important applied areas: computational

ge-ometry and operations research.

The

closest-pair problem calls for finding the two closest points in a set of n points. It is the simplest of a

variety of problems in computational geometry that deals with proximity of

points in the plane or higher-dimensional spaces. Points in question can

represent such physical objects as airplanes or post offices as well as

database records, statistical samples, DNA sequences, and so on. An air-traffic

controller might be interested in two closest planes as the most probable

collision candidates. A regional postal service manager might need a solution

to the closest-pair problem to find candidate post-office locations to be

closed.

One of

the important applications of the closest-pair problem is cluster analy-sis in

statistics. Based on n data

points, hierarchical cluster analysis seeks to orga-nize them in a hierarchy of

clusters based on some similarity metric. For numerical data, this metric is

usually the Euclidean distance; for text and other nonnumerical data, metrics

such as the Hamming distance (see Problem 5 in this section’s ex-ercises) are used.

A bottom-up algorithm begins with each element as a separate cluster and merges

them into successively larger clusters by combining the closest pair of

clusters.

For

simplicity, we consider the two-dimensional case of the closest-pair prob-lem.

We assume that the points in question are specified in a standard fashion by

their (x, y) Cartesian coordinates and that

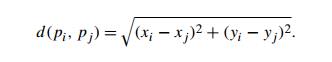

the distance between two points pi(xi, yi) and pj (xj , yj ) is the

standard Euclidean distance

The

brute-force approach to solving this problem leads to the following ob-vious

algorithm: compute the distance between each pair of distinct points and find a

pair with the smallest distance. Of course, we do not want to compute the

distance between the same pair of points twice. To avoid doing so, we consider

only the pairs of points (pi,

pj ) for

which i < j .

Closest-Pair and Convex-Hull Problems by

Brute Force

Pseudocode

below computes the distance between the two closest points; getting the closest

points themselves requires just a trivial modification.

ALGORITHM BruteForceClosestPair(P )

//Finds

distance between two closest points in the plane by brute force

//Input:

A list P of n

(n ≥ 2) points p1(x1, y1), . . . , pn(xn, yn)

//Output: The distance between the closest pair of points

d ←

∞

for i ← 1 to n − 1 do

for j ← i + 1 to n do

d ← min(d, sqrt((xi − xj )2 + (yi

− yj )2)) //sqrt is square

root

return d

The basic

operation of the algorithm is computing the square root. In the age of

electronic calculators with a square-root button, one might be led to believe

that computing the square root is as simple an operation as, say, addition or

multiplication. Of course, it is not. For starters, even for most integers,

square roots are irrational numbers that therefore can be found only

approximately. Moreover, computing such approximations is not a trivial matter.

But, in fact, computing square roots in the loop can be avoided! (Can you think

how?) The trick is to realize that we can simply ignore the square-root

function and compare the values (xi

− xj )2 + (yi

− yj )2 themselves. We can do this

because the smaller a number of which we

take the square root, the smaller its square root, or, as mathematicians say,

the square-root function is strictly increasing.

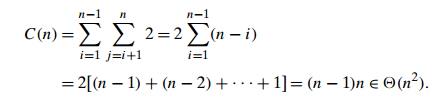

Then the

basic operation of the algorithm will be squaring a number. The number of times

it will be executed can be computed as follows:

Of

course, speeding up the innermost loop of the algorithm could only de-crease

the algorithm’s running time by a constant factor (see Problem 1 in this

section’s exercises), but it cannot improve its asymptotic efficiency class. In

Chap-ter 5, we discuss a linearithmic algorithm for this problem, which is

based on a more sophisticated design technique.

Convex-Hull

Problem

On to the

other problem—that of computing the convex hull. Finding the convex hull for a

given set of points in the plane or a higher dimensional space is one of the

most important—some people believe the most important—problems in

com-putational geometry. This prominence is due to a variety of applications in

which this problem needs to be solved, either by itself or as a part of a

larger task. Sev-eral such applications are based on the fact that convex hulls

provide convenient approximations of object shapes and data sets given. For

example, in computer an-imation, replacing objects by their convex hulls speeds

up collision detection; the same idea is used in path planning for Mars mission

rovers. Convex hulls are used in computing accessibility maps produced from

satellite images by Geographic Information Systems. They are also used for

detecting outliers by some statisti-cal techniques. An efficient algorithm for

computing a diameter of a set of points, which is the largest distance between

two of the points, needs the set’s convex hull to find the largest distance

between two of its extreme points (see below). Finally, convex hulls are

important for solving many optimization problems, because their extreme points

provide a limited set of solution candidates.

We start

with a definition of a convex set.

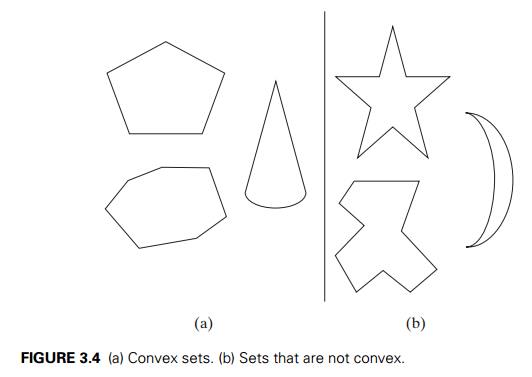

DEFINITION

A set of

points (finite or infinite) in the plane is called convex if for any two points p and q in the

set, the entire line segment with the endpoints at p and q belongs to the set.

All the

sets depicted in Figure 3.4a are convex, and so are a straight line, a

triangle, a rectangle, and, more generally, any convex polygon,1 a

circle, and the entire plane. On the other hand, the sets depicted in Figure

3.4b, any finite set of two or more distinct points, the boundary of any convex

polygon, and a circumference are examples of sets that are not convex.

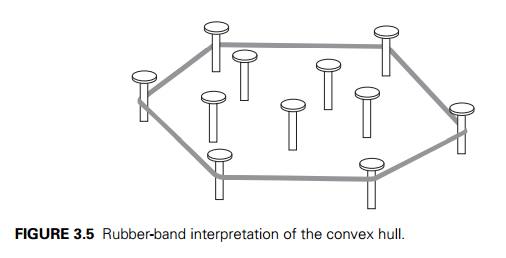

Now we

are ready for the notion of the convex hull. Intuitively, the convex hull of a

set of n points in the plane is the

smallest convex polygon that contains all of them either inside or on its

boundary. If this formulation does not fire up your enthusiasm, consider the

problem as one of barricading n sleeping

tigers by a fence of the shortest length. This interpretation is due to D.

Harel [Har92]; it is somewhat lively, however, because the fenceposts have to

be erected right at the spots where some of the tigers sleep! There is another,

much tamer interpretation of this notion. Imagine that the points in question

are represented by nails driven into a large sheet of plywood representing the

plane. Take a rubber band and stretch it to include all the nails, then let it

snap into place. The convex hull is the area bounded by the snapped rubber band

(Figure 3.5).

A formal

definition of the convex hull that is applicable to arbitrary sets, including

sets of points that happen to lie on the same line, follows.

DEFINITION

The convex

hull of a set S of points is the smallest convex

set

containing

S. (The “smallest” requirement

means that the convex hull of S must be

a subset of any convex set containing S.)

If S is convex, its convex hull is

obviously S itself. If S is a set of two points, its

convex hull is the line segment connecting these points. If S is a set of three

points

not on the same line, its convex hull is the triangle with the vertices at the

three points given; if the three points do lie on the same line, the convex

hull is the line segment with its endpoints at the two points that are farthest

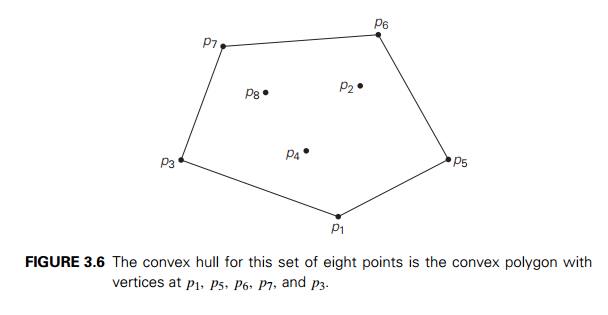

apart. For an example of the convex hull for a larger set, see Figure 3.6.

A study

of the examples makes the following theorem an expected result.

THEOREM The

convex hull of any set S of n > 2 points

not all on the same line is a convex polygon with the

vertices at some of the points of S. (If all

the points do lie on the same line, the polygon degenerates to a line segment

but still with the endpoints at two points of S.)

The convex-hull

problem is the problem of constructing the convex hull for a given set S of n points.

To solve it, we need to find the points that will serve as the vertices of the

polygon in question. Mathematicians call the vertices of such a polygon

“extreme points.” By definition, an extreme point of a convex set is a

point of this set that is not a middle point of any line segment with endpoints

in the set. For example, the extreme points of a triangle are its three

vertices, the extreme points of a circle are all the points of its

circumference, and the extreme points of the convex hull of the set of eight

points in Figure 3.6 are p1, p5, p6, p7,

and p3.

Extreme

points have several special properties other points of a convex set do not

have. One of them is exploited by the simplex method, a very important

algorithm discussed in Section 10.1. This algorithm solves linear programming

problems, which are problems of finding a minimum or a maximum of a linear

function of n variables subject to linear

constraints (see Problem 12 in this section’s exercises for an example and

Sections 6.6 and 10.1 for a general discussion). Here, however, we are

interested in extreme points because their identification solves the

convex-hull problem. Actually, to solve this problem completely, we need to

know a bit more than just which of n points

of a given set are extreme points of the set’s convex hull: we need to know

which pairs of points need to be connected to form the boundary of the convex

hull. Note that this issue can also be addressed by listing the extreme points

in a clockwise or a counterclockwise order.

So how

can we solve the convex-hull problem in a brute-force manner? If you do not see

an immediate plan for a frontal attack, do not be dismayed: the convex-hull

problem is one with no obvious algorithmic solution. Nevertheless, there is a

simple but inefficient algorithm that is based on the following observation

about line segments making up the boundary of a convex hull: a line segment

connecting two points pi and pj of a set

of n points is a part of the convex

hull’s boundary if and only if all the other points of the set lie on the same

side of the straight line through these two points.2 (Verify this

property for the set in Figure 3.6.) Repeating this test for every pair of

points yields a list of line segments that make up the convex hull’s boundary.

A few

elementary facts from analytical geometry are needed to implement this

algorithm. First, the straight line through two points (x1, y1), (x2, y2) in the coordinate plane can be

defined by the equation

ax + by = c,

where a = y2 − y1, b = x1 − x2, c = x1y2 − y1x2.

Second,

such a line divides the plane into two half-planes: for all the points in one

of them, ax + by > c, while for all the points in the

other, ax + by < c. (For the points on the line

itself, of course, ax + by = c.) Thus,

to check whether certain points lie on the same side of the line, we can simply

check whether the expression ax + by − c has the

same sign for each of these points. We leave the implementation details as an

exercise.

What is

the time efficiency of this algorithm? It is in O(n3): for each of n(n − 1)/2 pairs of distinct points, we

may need to find the sign of ax + by − c for each

of the other n − 2

points. There are much more efficient algorithms for this important problem,

and we discuss one of them later in the book.

Exercises

3.3

1. Assuming that sqrt takes about 10 times longer than each of the other oper-ations in the innermost loop of BruteForceClosestPoints, which are assumed to take the same amount of time, estimate how much faster the algorithm will run after the improvement discussed in Section 3.3.

2. Can you design a more efficient algorithm than the one based on the brute-force strategy to solve the closest-pair problem for n points x1, x2, . . . , xn on the real line?

3. Let x1 < x2 < . . . < xn be real numbers representing coordinates of n villages located along a straight road. A post office needs to be built in one of these villages.

Design an efficient algorithm to find the

post-office location minimizing the average distance between the villages and

the post office.

Design an efficient algorithm to find the

post-office location minimizing the maximum distance from a village to the post

office.

4. a. There are several alternative ways to define a distance between two points p1(x1, y1) and p2(x2, y2) in the Cartesian plane. In particular, the Manhat-tan distance is defined as

dM (p1, p2) =

|x1 − x2| + |y1 − y2|.

Prove

that dM

satisfies the following axioms, which every distance function must satisfy:

dM

(p1, p2) ≥ 0 for any

two points p1 and

p2, and dM (p1, p2) = 0 if and only if p1 = p2

dM

(p1, p2) = dM

(p2, p1)

dM

(p1, p2) ≤ dM

(p1, p3) + dM

(p3, p2) for any p1, p2, and

p3

Sketch all the points in the Cartesian plane whose

Manhattan distance to the origin (0, 0) is equal

to 1. Do the same for the Euclidean distance.

True or false: A solution to the closest-pair

problem does not depend on which of the two metrics—dE

(Euclidean) or dM

(Manhattan)—is used?

5. The Hamming distance between two strings of equal length is defined as the number of positions at which the corresponding symbols are different. It is named after Richard Hamming (1915–1998), a prominent American scientist and engineer, who introduced it in his seminal paper on error-detecting and error-correcting codes.

Does the Hamming distance satisfy the three axioms

of a distance metric listed in Problem 4?

What is the time efficiency class of the

brute-force algorithm for the closest-pair problem if the points in question

are strings of m symbols

long and the distance between two of them is measured by the Hamming distance?

6. Odd pie fight There are n ≥ 3 people positioned on a field (Euclidean plane) so that each has a unique nearest neighbor. Each person has a cream pie. At a signal, everybody hurls his or her pie at the nearest neighbor. Assuming that n is odd and that nobody can miss his or her target, true or false: There always remains at least one person not hit by a pie. [Car79]

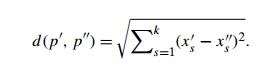

7. The

closest-pair problem can be posed in the k-dimensional

space, in which the Euclidean distance between two points p (x1, . . . , xk) and p (x1 , . . . , xk ) is defined as

What is

the time-efficiency class of the brute-force algorithm for the k-dimensional closest-pair

problem?

8. Find the convex hulls of the following sets and

identify their extreme points (if they have any):

a. a line

segment

a square

the boundary of a square

a straight line

9. Design a linear-time algorithm to determine two

extreme points of the convex hull of a given set of n

> 1 points in the plane.

10. What modification needs to be made in the

brute-force algorithm for the convex-hull problem to handle more than two

points on the same straight line?

11. Write a program implementing the brute-force

algorithm for the convex-hull problem.

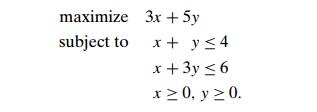

12. Consider the following small instance of the linear

programming problem:

Sketch, in the Cartesian plane, the problem’s feasible

region, defined as the set of points satisfying all the problem’s

constraints.

Identify the region’s extreme points.

Solve this optimization problem by using the

following theorem: A linear programming problem with a nonempty bounded

feasible region always has a solution, which can be found at one of the extreme

points of its feasible region.

Related Topics