Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Management of Patients With Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: Medical and Nursing Management

Medical Management

RISK REDUCTION

Smoking

cessation is the single most effective intervention to prevent COPD or slow its

progression (NIH, 2001). Recent sur-veys indicate that 25% of all American

adults smoke (USPHS, 2000). Nurses play a key role in promoting smoking

cessation and educating patients about ways to do so. Patients diagnosed with

COPD who continue to smoke must be encouraged and as-sisted to quit. Factors

associated with continued smoking vary among patients and may include the

strength of nicotine addic-tion, continued exposure to smoking-associated

stimuli (at work or in social settings), stress, depression, and habit.

Continued smoking is also more prevalent among those with low incomes, a low

level of education, and psychosocial problems (Pohl, 2000).

Because

there are multiple factors associated with continued smoking, successful

cessation often requires multiple strategies. The health care provider should

promote cessation by explaining the risks of smoking and personalizing the

“at-risk” message to the patient. After giving a strong warning about smoking,

the health care provider should work with the patient to set a definite “quit

date.” Referral to a smoking cessation program may be helpful. Follow-up within

3 to 5 days after the quit date to review progress and to address any problems

is associated with an increased rate of success; this should be repeated as

needed. Continued rein-forcement with telephone calls or clinic visits is

extremely bene-ficial. Relapses should be analyzed, and the patient and health

care provider should jointly identify possible solutions to prevent future backsliding.

It is important to emphasize successes rather than failures. First-line

pharmacotherapies that reliably increase long-term smoking abstinence rates are

bupropion SR (Zyban, Wellbutrin), nicotine gum, nicotine inhaler, nicotine

nasal spray, or nicotine patches. Second-line pharmacotherapies include

clonidine (Catapres) and nortriptyline (Aventyl) (USPHS, 2000).

Smoking

cessation can begin in a variety of health care settings— outpatient clinic,

pulmonary rehabilitation, community, hospital, and the patient’s home.

Regardless of the setting, the nurse has the opportunity to teach the patient

about the risks of smoking and the benefits of smoking cessation. A variety of

materials, re-sources, and programs are available to assist with this effort

(eg, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality [formerly Agency for Healthcare

Policy and Research], United States Public Health Service, Centers for Disease

Control and Prevention, National Cancer Institute, American Lung Association,

American Cancer Society).

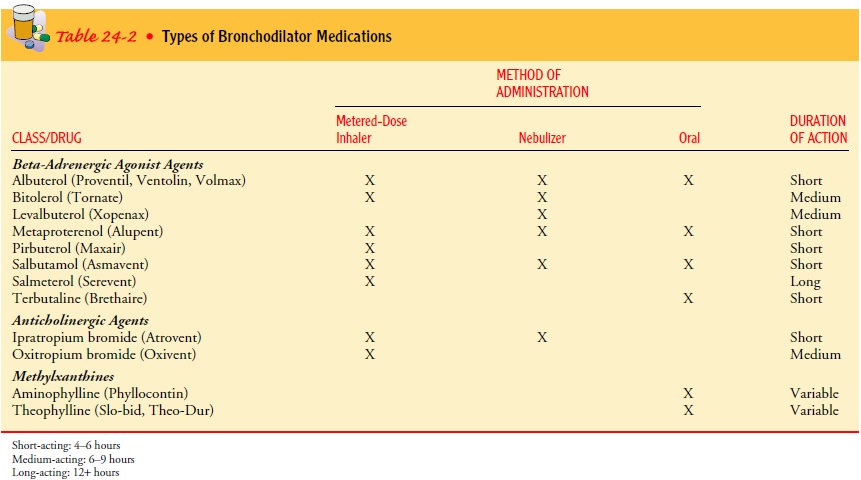

PHARMACOLOGIC THERAPY

Bronchodilators.

Bronchodilators

relieve bronchospasm and re-duce airway obstruction by allowing increased

oxygen distribu-tion throughout the lungs and improving alveolar ventilation.

These medications, which are central in the management of COPD (NIH, 2001), are

delivered through a metered-dose inhaler, by nebulization, or via the oral

route in pill or liquid form. Bron-chodilators are often administered regularly

throughout the day as well as on an as-needed basis. They may also be used

prophy-lactically to prevent breathlessness by having the patient use them

before an activity, such as eating or walking.

metered-dose

inhaler (MDI) is a pressurized device con-taining an aerosolized

powder of medication. A precise amount of medication is released with each

activation of the canister (Dhand, 2000). Patients need to be instructed on the

correct use of the device. A spacer (holding chamber) may also be used to

en-hance deposition of the medication in the lung and help the pa-tient coordinate

activation of the MDI with inspiration. Spacers come in several designs, but

all are attached to the MDI and have a mouthpiece on the opposite end (Fig.

24-5). Once the canister is activated, the spacer holds the aerosol in the

chamber until the patient inhales (Dhand, 2000). The patient should take a

slow, 3- to 5-second inhalation immediately following activation of the MDI

(Expert Panel Report II, 1997).

Several

classes of bronchodilators are used: beta-adrenergic agonists, anticholinergic

agents, and methylxanthines. These medications may be used in combination to

optimize the bron-chodilation effect. Some of these medications are

short-acting; others are long-acting. Long-acting bronchodilators are more

con-venient for patient use. Examples of medications in these differ-ing

classes are shown in Table 24-2. Nebulized medications (nebulization of

medication via an air compressor) may also be effective in patients who cannot

use an MDI properly or who pre-fer this method of administration.

Corticosteroids.

Inhaled

and systemic corticosteroids (oral orintravenous) may also be used in COPD but

are used more fre-quently in asthma. Although it has been shown that

cortico-steroids do not slow the decline in lung function, these medications

may improve symptoms. A short trial course of oral cortico-steroids may be

prescribed for patients with stage II or III COPD to see if pulmonary function

improves and symptoms decrease. Inhaled corticosteroids via MDI may also be

used. Examples of corticosteroids in the inhaled form are beclomethasone

(Beclovent, Vanceril), budesonide (Pulmicort), flunisolide (AeroBid),

fluti-casone (Flovent), and triamcinolone (Azmacort).

Medication regimens used to manage COPD are based on disease severity. For stage I or mild COPD, a short-acting bron chodilator may be prescribed. For stage II or moderate COPD, one or more bronchodilators may be prescribed along with in-haled corticosteroids, if symptoms are significant. For stage III or severe COPD, medication therapy includes regular treatment with one or more bronchodilators and inhaled corticosteroids (NIH, 2001).

Other Medications.

Patients

should receive a yearly influenzavaccine and the pneumococcal vaccine every 5

to 7 years as pre-ventive measures. In most healthy adults, pneumococcal

vaccine titers persist for 5 or more years (George, San Pedro & Stoller,

2000). Other pharmacologic treatments that may be used in COPD include alpha1 antitrypsin augmentation therapy, anti-biotic

agents, mucolytic agents, and antitussive agents.

MANAGEMENT OF EXACERBATION

An

exacerbation of COPD is difficult to diagnose, but signs and symptoms may

include increased dyspnea, increased sputum pro-duction and purulence,

respiratory failure, changes in mental sta-tus, or worsening blood gas

abnormalities. Primary causes for an acute exacerbation include

tracheobronchial infection and air pollution (NIH, 2001). Secondary causes are

pneumonia; pul-monary embolism; pneumothorax; rib fractures or chest trauma;

inappropriate use of sedative, opioid, or beta-blocking agents; and right- or

left-sided heart failure. First, the primary cause of the exacerbation is

identified, and then specific treatment is ad-ministered. Optimization of

bronchodilator medications is the first-line therapy and involves identifying

the best medication or combinations of medications taken on a regular schedule

for that patient. Depending on the signs and symptoms, corticosteroids,

antibiotic agents, oxygen therapy, and intensive respiratory in-terventions may

also be used. Indications for hospitalization of a patient with an acute

exacerbation of COPD include severe dys-pnea that does not respond adequately

to initial therapy, confusion or lethargy, respiratory muscle fatigue, paradoxical

chest wall movement, peripheral edema, worsening or new onset of central

cyanosis, persistent or worsening hypoxemia, and/or need for noninvasive or

invasive assisted mechanical ventilation (Celli, Snider, Heffner et al., 1995;

NIH, 2001).

OXYGEN THERAPY

Oxygen therapy can be administered as long-term continuous therapy, during exercise, or to prevent acute dyspnea. Long-term oxygen therapy has been shown to improve the patient’s quality of life and survival (NIH, 2001). For patients with an arterial oxygen pressure (PaO2) of 55 mm Hg or less on room air, maintaining a constant and adequate oxygen saturation (>90%) is associated with significantly reduced mortality and improved quality of life. Indications for oxygen supplementa-tion include a PaO2 of 55 mm Hg or less or evidence of tissue hypoxia and organ damage such as cor pulmonale, secondary polycythemia, edema from right heart failure, or impaired men-tal status. In patients with exercise-induced hypoxemia, oxygen supplementation during exercise can improve performance. Pa-tients who are hypoxemic while awake are likely to be so during sleep. Therefore, nighttime oxygen therapy is recommended as well, and the prescription for oxygen therapy is for continuous, 24-hour use. Intermittent oxygen therapy is indicated for those who desaturate only during exercise or sleep.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Bullectomy.

A

bullectomy is a surgical option for select patientswith bullous emphysema.

Bullae are enlarged airspaces that do not contribute to ventilation but occupy

space in the thorax; these areas may be surgically excised. Many times these

bullae compress areas of the lung that do have adequate gas exchange.

Bullectomy may help reduce dyspnea and improve lung function. It can be done

thoracoscopically (with a video-assisted thoraco-scope) or via a limited

thoracotomy incision.

Lung Volume Reduction Surgery.

Treatment options for patientswith end-stage COPD (stage III) with

a primary emphysematous component are limited, although lung volume reduction

surgery is an option for a specific subset of patients. This subset includes

patients with homogenous disease or disease that is focused in one area and not

widespread throughout the lungs. Lung volume re-duction surgery involves the

removal of a portion of the diseased lung parenchyma. This allows the

functional tissue to expand, re-sulting in improved elastic recoil of the lung

and improved chest wall and diaphragmatic mechanics. This type of surgery does

not cure the disease, but it may decrease dyspnea, improve lung func-tion, and

improve the patient’s overall quality of life. Careful se-lection of patients

for this procedure is essential to decrease the morbidity and mortality. The

long-term outcomes of this surgery are unknown.

The

National Emphysema Treatment Trial (NETT) is a large, multicenter randomized

clinical trial that began in 1997 and is ongoing. It is attempting to answer

many questions regarding the risks and benefits of lung volume reduction

surgery in the treat-ment of severe emphysema. All patients in this trial

receive a 6-to 10-week pulmonary rehabilitation program and comprehen-sive

medical management. Following completion of pulmonary rehabilitation, patients

are randomized to continue medical man-agement or undergo lung volume reduction

surgery. The results of this trial will help to determine the role of lung

volume reduc-tion surgery for patients with severe emphysema (NIH, 2001). It is

expected that 2,500 patients will be entered into the study.

Lung Transplantation.

Lung

transplantation is a viable alterna-tive for definitive surgical treatment of

end-stage emphysema. It has been shown to improve quality of life and

functional capac-ity (NIH, 2001). Specific criteria exist for referral for lung

trans-plantation; however, organs are in short supply and many patients die

while waiting for a transplant.

PULMONARY REHABILITATION

Pulmonary

rehabilitation for patients with COPD is well estab-lished and widely accepted

as a means to alleviate symptoms and optimize functional status. In both

randomized and nonrandom-ized clinical trials, pulmonary rehabilitation has

been shown to improve exercise tolerance, reduce dyspnea, and increase

health-related quality of life (Rochester, 2000). The primary goal of

re-habilitation is to restore patients to the highest level of independent

function possible and to improve their quality of life. A suc-cessful

rehabilitation program is individualized for each patient, is

multidisciplinary, and attends to both the physiologic and emotional needs of

the patient. Most pulmonary rehabilitation programs include educational,

psychosocial, behavioral, and physical components. Breathing exercises and

retraining and ex-ercise programs are used to improve functional status, and

the pa-tient is taught methods to alleviate symptoms.

Pulmonary

rehabilitation may be used therapeutically in other diseases besides COPD,

including asthma, cystic fibrosis, lung cancer, interstitial lung disease,

thoracic surgery, and lung trans-plantation. It may be conducted in the

inpatient, outpatient, or home setting; the lengths of programs vary. Selection

of a program depends upon the patient’s physical, functional, and psychosocial

status; insurance coverage; changing health care trends; availabil-ity of

programs; and patient preference (Rochester, 2000).

Nursing Management

The

nurse plays a key role in identifying potential candidates for pulmonary

rehabilitation and in facilitating and reinforcing the material learned in the

rehabilitation program. Not all patients have access to a formal rehabilitation

program. However, the nurse can be instrumental in teaching the patient and

family as well as facilitating specific services for the patient (eg,

respiratory therapy education, physical therapy for exercise and breathing

re-training, occupational therapy for conserving energy during ac-tivities of

daily living, and nutritional counseling). In addition, numerous educational

materials are available to assist the nurse in teaching patients with COPD.

Potential resources include the American Lung Association, the American

Association of Cardio-vascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation, the American

Thoracic Society, the American College of Chest Physicians, and the Amer-ican

Association for Respiratory Therapy.

PATIENT EDUCATION

Patient

education is a major component of pulmonary rehabili-tation and includes a

broad variety of topics. Depending on the length and setting of the program,

topics may include normal anatomy and physiology of the lung, pathophysiology

and changes with COPD, medications and home oxygen therapy, nutrition,

respiratory therapy treatments, symptom alleviation, smoking cessation,

sexuality and COPD, coping with chronic disease, communicating with the health

care team, and planning for the future (advance directives, living wills,

informed decision making about health care alternatives).

Breathing Exercises.

The

breathing pattern of most people withCOPD is shallow, rapid, and inefficient;

the more severe the dis-ease, the more inefficient the breathing pattern. With

practice, this type of upper chest breathing can be changed to diaphrag-matic

breathing, which reduces the respiratory rate, increases alveolar ventilation,

and sometimes helps expel as much air as possible during expiration. Pursed-lip

breathing helps to slow expiration, prevents collapse of small airways, and

helps the patient to control the rate and depth of res-piration. It also

promotes relaxation, enabling the patient to gain control of dyspnea and reduce

feelings of panic.

Inspiratory Muscle Training.

Once the patient masters dia-phragmatic breathing, a program of

inspiratory muscle training may be prescribed to help strengthen the muscles

used in breath-ing. This program requires that the patient breathe against

resis-tance for 10 to 15 minutes every day. As the resistance is gradually

increased, the muscles become better conditioned. Conditioning of the

respiratory muscles takes time, and the patient is instructed to continue

practicing at home (Larson, Covey, Wirtz et al., 1999; NIH, 2001).

Activity Pacing.

A

patient with COPD has decreased exercisetolerance during specific periods of

the day. This is especially true on arising in the morning, because bronchial

secretions collect in the lungs during the night while the person is lying

down. The patient may have difficulty bathing or dressing. Activities

requir-ing the arms to be supported above the level of the thorax may produce

fatigue or respiratory distress but may be tolerated bet-ter after the patient

has been up and moving around for an hour or more. Working with the nurse, the

patient can reduce these limitations by planning self-care

activities and determining the best time for bathing, dressing, and daily

activities.

Self-Care Activities.

As

gas exchange, airway clearance, and thebreathing pattern improve, the patient

is encouraged to assume increasing participation in self-care activities. The

patient is taught to coordinate diaphragmatic breathing with activities such as

walking, bathing, bending, or climbing stairs. The patient should bathe, dress,

and take short walks, resting as needed to avoid fa-tigue and excessive

dyspnea. Fluids should always be readily avail-able, and the patient should

begin to drink fluids without having to be reminded. If postural drainage is to

be done at home, the nurse instructs and supervises the patient before

discharge or in the outpatient setting.

Physical Conditioning.

Physical conditioning techniques in-clude breathing exercises and

general exercises intended to con-serve energy and increase pulmonary

ventilation. There is a close relationship between physical fitness and

respiratory fit-ness. Graded exercises and physical conditioning programs using

treadmills, stationary bicycles, and measured level walks can improve symptoms

and increase work capacity and exercise tolerance. Any physical activity that

can be done regularly is helpful. Lightweight portable oxygen systems are

available for ambulatory patients who require oxygen therapy during physi-cal

activity.

Oxygen Therapy.

Oxygen

supplied to the home comes in com-pressed gas, liquid, or concentrator systems.

Portable oxygen sys-tems allow the patient to exercise, work, and travel. To

help the patient adhere to the oxygen prescription, the nurse explains the proper

flow rate and required number of hours for oxygen use as well as the dangers of

arbitrary changes in flow rates or duration of therapy. The nurse cautions the

patient that smoking with or near oxygen is extremely dangerous. The nurse also

reassures the patient that oxygen is not “addictive” and explains the need for

regular evaluations of blood oxygenation by pulse oximetry or arterial blood

gas analysis.

Nutritional Therapy.

Nutritional

assessment and counseling areimportant aspects in the rehabilitation process

for the patient with COPD. Approximately 25% of patients with COPD are

undernourished (NIH, 2001; Ferreira, Brooks, Lacasse & Gold-stein, 2001). A

thorough assessment of caloric needs and coun-seling about meal planning and

supplementation are part of the rehabilitation process.

Coping Measures.

Any

factor that interferes with normal breath-ing quite naturally induces anxiety,

depression, and changes in behavior. Many patients find the slightest exertion

exhausting. Constant shortness of breath and fatigue may make the patient

irritable and apprehensive to the point of panic. Restricted activ-ity (and

reversal of family roles due to loss of employment), the frustration of having

to work to breathe, and the realization that the disease is prolonged and

unrelenting may cause the patient to react with anger, depression, and

demanding behavior. Sexual function may be compromised, which also diminishes

self-esteem. In addition, the nurse needs to provide education and support to

the spouse/significant other and family because the caregiver role in end-stage

COPD can be difficult.

Related Topics