Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Management of Patients With Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

Asthma

Asthma

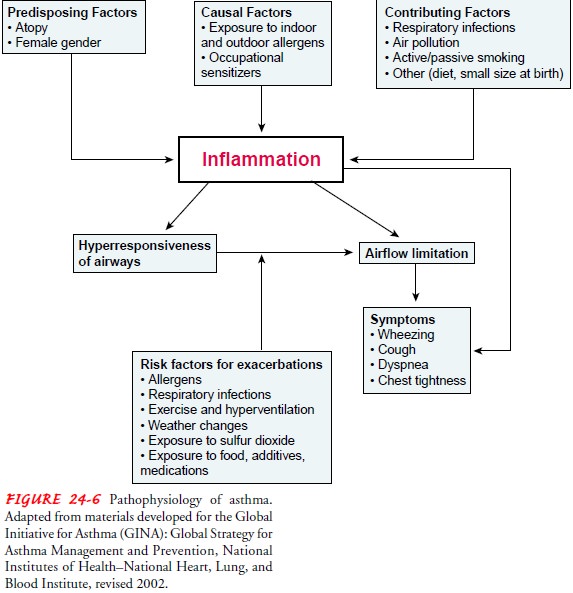

Asthma is a

chronic inflammatory disease of the airways thatcauses airway

hyperresponsiveness, mucosal edema, and mucus production. This inflammation

ultimately leads to recurrent episodes of asthma symptoms: cough, chest

tightness, wheezing, and dyspnea (Fig. 24-6). Estimates show that nearly 17

million Americans have asthma, and more than 5,000 die from this dis-ease

annually (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 1998; CDC, 1999;

NCHS, 2001). In 1998, asthma ac-counted for over 13.9 million outpatient visits

to physician of-fices or hospital clinics and over 2.0 million emergency room

visits (NCHS, 2001).

Asthma

differs from the other obstructive lung diseases in that it is largely

reversible, either spontaneously or with treatment. Pa-tients with asthma may

experience symptom-free periods alter-nating with acute exacerbations, which

last from minutes to hours or days. Asthma can occur at any age and is the most

com-mon chronic disease of childhood. Despite increased knowledge regarding the

pathology of asthma and the development of bet-ter medications and management

plans, the death rate from asthma continues to increase. For most patients it

is a disruptive disease, affecting school and work attendance, occupational

choices, physical activity, and general quality of life.

Allergy is the strongest predisposing factor for asthma. Chronic exposure to airway irritants or allergens also increases the risk for developing asthma. Common allergens can be seasonal (eg, grass, tree, and weed pollens) or perennial (eg, mold, dust, roaches, or animal dander). Common triggers for asthma symptoms and exacerbations in patients with asthma include airway irritants (eg, air pollutants, cold, heat, weather changes, strong odors or perfumes, smoke), exercise, stress or emotional upsets, sinusitis with postnasal drip, medications, viral respiratory tract infections, and gastroesophageal reflux. Most people who have asthma are sensitive to a variety of triggers. A patient’s asthma condition will change depending upon the environment, activities, manage-ment practices, and other factors (NHLBI, 1998).

Pathophysiology

The

underlying pathology in asthma is reversible and diffuse air-way inflammation.

The inflammation leads to obstruction from the following: swelling of the

membranes that line the airways (mucosal edema), reducing the airway diameter;

contraction of the bronchial smooth muscle that encircles the airways

(bron-chospasm), causing further narrowing; and increased mucus pro-duction,

which diminishes airway size and may entirely plug the bronchi.

The

bronchial muscles and mucus glands enlarge; thick, tena-cious sputum is

produced; and the alveoli hyperinflate. Some pa-tients may have airway

subbasement membrane fibrosis. This is called airway “remodeling” and occurs in

response to chronic in-flammation. The fibrotic changes in the airway lead to

airway nar-rowing and potentially irreversible airflow limitation (NIH, 2001;

NHLBI, 1998).

Cells

that play a key role in the inflammation of asthma are mast cells, neutrophils,

eosinophils, and lymphocytes. Mast cells, when activated, release several

chemicals called mediators. These chemicals, which include histamine,

bradykinin, prostaglandins, and leukotrienes, perpetuate the inflammatory

response, causing increased blood flow, vasoconstriction, fluid leak from the

vascu-lature, attraction of white blood cells to the area, and

broncho-constriction (NHLBI, 1998). Regulation of these chemicals is the aim of

much of the current research regarding pharmacologic therapy for asthma.

Further,

alpha- and beta2-adrenergic receptors of the

sympa-thetic nervous system are located in the bronchi. When the

alpha-adrenergic receptors are stimulated, bronchoconstriction occurs; when the

beta2-adrenergic receptors are stimulated, bronchodilation results.

The balance between alpha and beta2 receptors is con-trolled

primarily by cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP). Alpha-adrenergic receptor

stimulation results in a decrease in cAMP, which leads to an increase of

chemical mediators released by the mast cells and bronchoconstriction. Beta2-receptor

stimulation results in increased levels of cAMP, which inhibits the release of

chemical mediators and causes bronchodilation (NHLBI, 1998).

Clinical Manifestations

The

three most common symptoms of asthma are cough, dysp-nea, and wheezing. In some

instances, cough may be the only symptom. Asthma attacks often occur at night

or early in the morning, possibly due to circadian variations that influence

air-way receptor thresholds.

An

asthma exacerbation may begin abruptly but most fre-quently is preceded by

increasing symptoms over the previous few days. There is cough, with or without

mucus production. At times the mucus is so tightly wedged in the narrowed

airway that the patient cannot cough it up. There may be generalized wheez-ing

(the sound of airflow through narrowed airways), first on ex-piration and then

possibly during inspiration as well. Generalized chest tightness and dyspnea

occur. Expiration requires effort and becomes prolonged. As the exacerbation progresses,

diaphoresis, tachycardia, and a widened pulse pressure may occur along with

hypoxemia and central cyanosis (a late sign of poor oxygenation). Although

life-threatening and severe hypoxemia can occur in asthma, it is relatively

uncommon. The hypoxemia is secondary to a ventilation–perfusion mismatch and

readily responds to sup-plemental oxygenation.Symptoms of exercise-induced

asthma include maximal symp-toms during exercise, absence of nocturnal

symptoms, and some-times only a description of a “choking” sensation during

exercise.

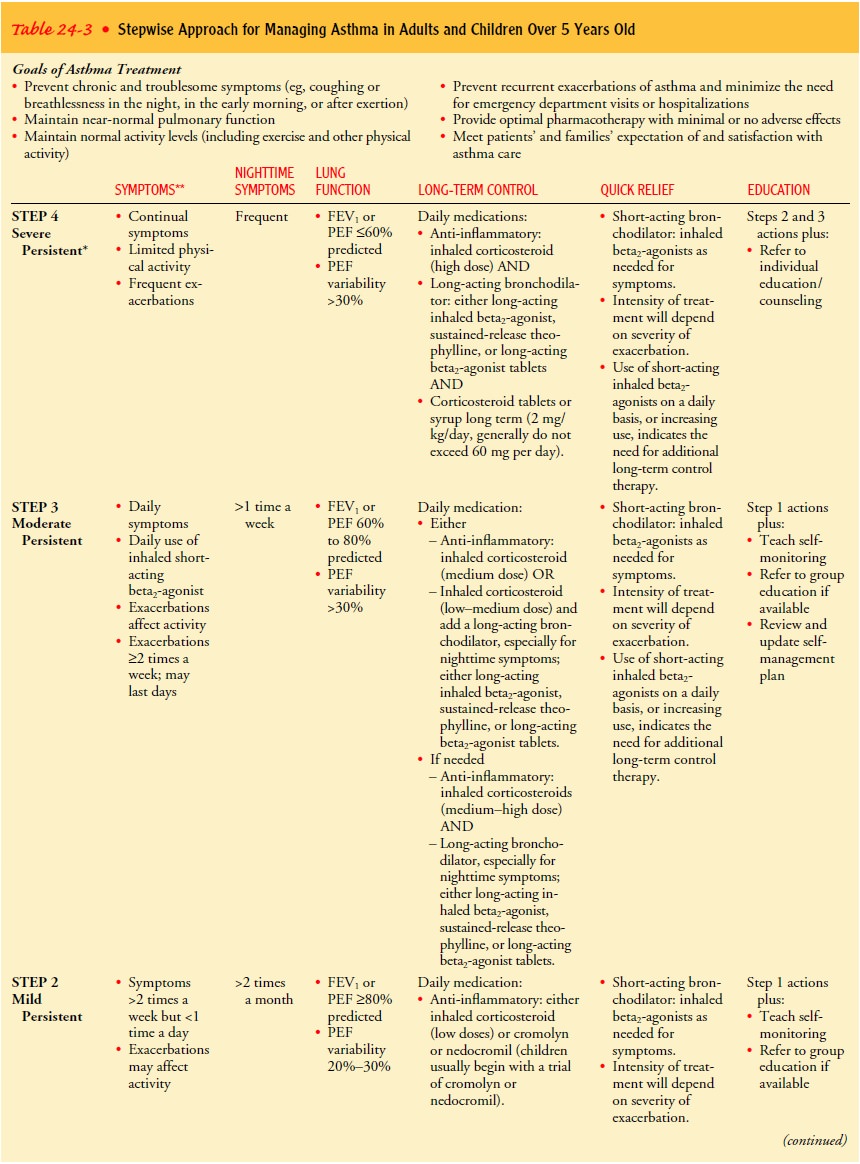

Asthma

is categorized according to symptoms and objective measures of airflow

obstruction (Table 24-3) (Expert Panel Re-port II, 1997).

Assessment and Diagnostic Findings

A

complete family, environmental, and occupational history is es-sential. To

establish the diagnosis, the clinician must determine that periodic symptoms of

airflow obstruction are present, air-flow is at least partially reversible, and

other etiologies have been excluded. A positive family history and

environmental factors, including seasonal changes, high pollen counts, mold,

climate changes (particularly cold air), and air pollution, are primarily

as-sociated with asthma. In addition, asthma is associated with a va-riety of

occupation-related chemicals and compounds, including metal salts, wood and

vegetable dust, medications (eg, aspirin, antibiotics, piperazine, cimetidine),

industrial chemicals and plas-tics, biologic enzymes (eg, laundry detergents),

animal and insect dusts, sera, and secretions. Comorbid conditions that may

ac-company asthma include gastroesophageal reflux, drug-induced asthma, and

allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis. Other pos-sible allergic reactions

that may accompany asthma include eczema, rashes, and temporary edema.

During

acute episodes, sputum and blood tests may disclose eosinophilia (elevated

levels of eosinophils). Serum levels of im-munoglobulin E may be elevated if

allergy is present. Arterial blood gas analysis and pulse oximetry reveal

hypoxemia during acute at-tacks. Initially, hypocapnia and respiratory

alkalosis are present. As the condition worsens and the patient becomes more

fatigued, the PaCO2 may rise.

A normal PaCO2 value may be a signal of im-pending

respiratory failure. Because CO2 is 20

times more dif-fusible than oxygen, it is rare for PaCO2

to be normal or elevated in a person who is breathing very rapidly. During an

exacerbation, the FEV1 and FVC

are markedly decreased but improve with bron-chodilator administration

(demonstrating reversibility). Pul-monary function is usually normal between

exacerbations.

The

occurrence of a severe, continuous reaction is referred to as status

asthmaticus and is considered life-threatening (see below).

Prevention

Patients

with recurrent asthma should undergo tests to identify the substances that

precipitate the symptoms. Possible causes are dust, dust mites, roaches,

certain types of cloth, pets, horses, de-tergents, soaps, certain foods, molds,

and pollens. If the attacks are seasonal, pollens can be strongly suspected.

The patient is in-structed to avoid the causative agents whenever possible.

Knowledge

is the key to quality asthma care. Although na-tional guidelines are available

for the care of the asthma patient, unfortunately health care providers may not

follow them. Failure to follow the guidelines in the following areas has been

noted: lack of treatment of patients who have symptoms more than 2 days per

week with a regular medication schedule, lack of patient-specific advice on

improving the environment and an explanation about the importance of doing so,

lack of encouragement for pa-tients to monitor their peak flow measurements

with a diary, and lack of written, up-to-date educational materials (Plaut,

2001).

A

1998 survey by a group called “Asthma in America” found that 11% of physicians

were unaware of the national asthma guidelines. Only 35% of patients with

asthma who were surveyed reported having pulmonary function testing in the past

year.

While

83% of physicians reported prescribing peak flow meter monitoring, only 62% of

patients had ever heard of a peak flow meter (Rickard & Stempel, 1999). All

health care providers caring for asthma patients need to be aware of the

national guidelines and use them (Expert Panel Report II, 1997).

Complications

Complications

of asthma may include status asthmaticus, respira-tory failure, pneumonia, and

atelectasis. Airway obstruction, particularly during acute asthmatic episodes,

often results in hy-poxemia, requiring the administration of oxygen and the

moni-toring of pulse oximetry and arterial blood gases. Fluids are administered

because people with asthma are frequently dehydrated from diaphoresis and

insensible fluid loss with hyperventilation.

Medical Management

Immediate

intervention is necessary because the continuing and progressive dyspnea leads

to increased anxiety, aggravating the situation.

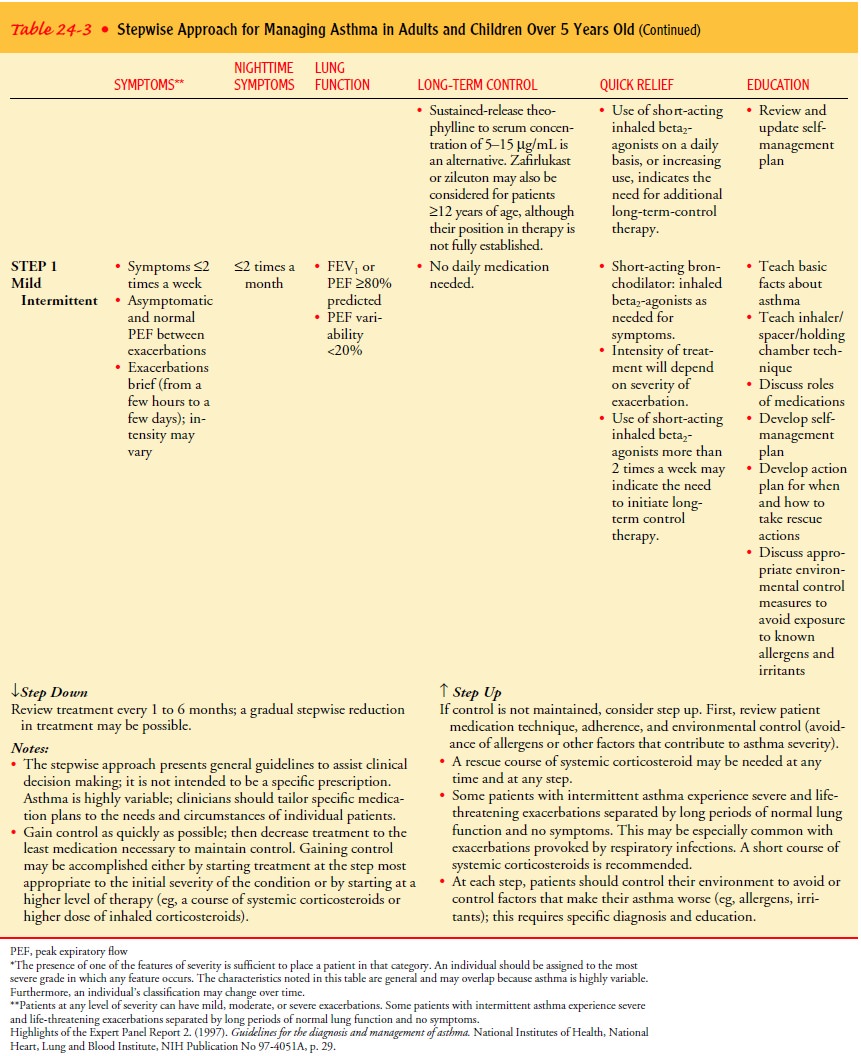

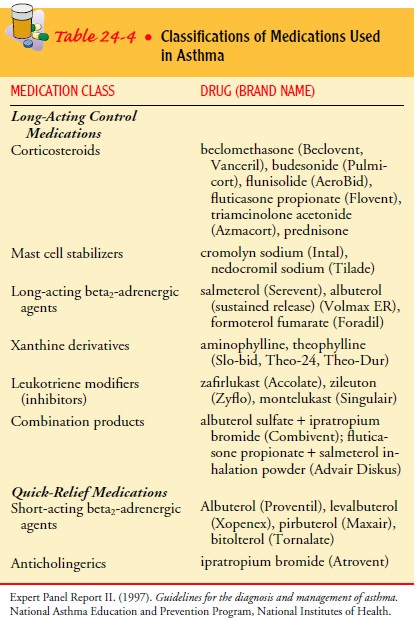

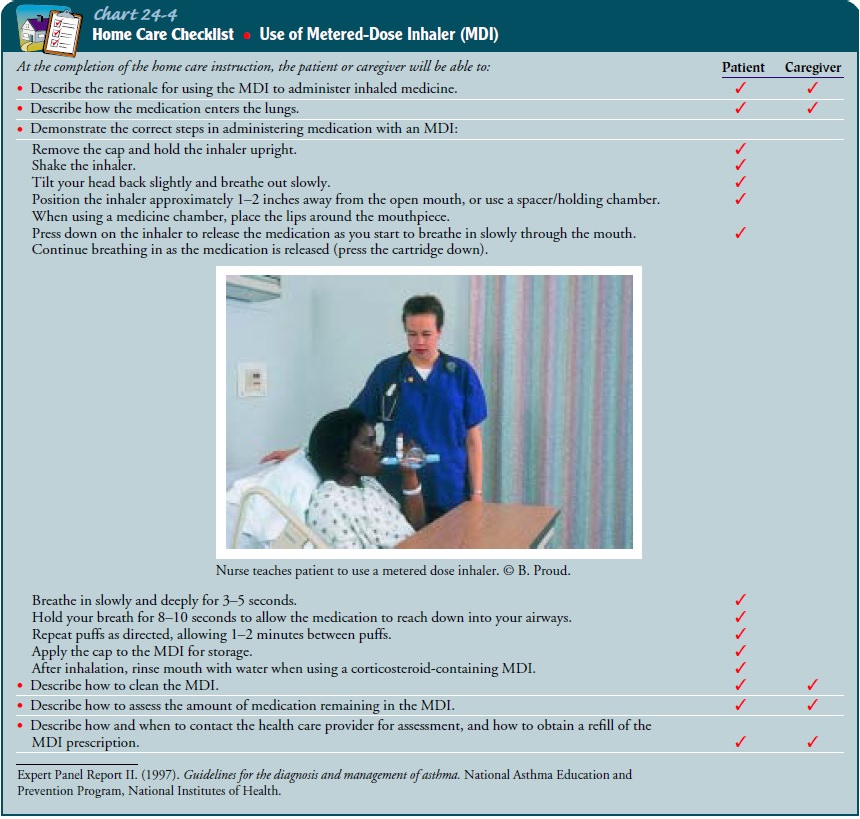

PHARMACOLOGIC THERAPY

Two

general classes of asthma medications are long-acting med-ications to achieve

and maintain control of persistent asthma and quick-relief medications for

immediate treatment of asthma symptoms and exacerbations (Table 24-4). Because

the under-lying pathology of asthma is inflammation, control of persistent

asthma is accomplished primarily with regular use of anti-inflammatory medications.

These medications have systemic side effects when used long term. The route of

choice for administra-tion of these medications is the MDI because it allows

for topical administration. Critical to the success of inhaled therapy is the

proper use of the MDI (see Chart 24-4). If the patient has diffi-culty with

this procedure, the use of a spacer device is indicated. Table 24-3 presents a

stepwise approach for managing asthma (Expert Panel Report II, 1997).

Information on use of the MDI and spacer device is given in the previous

section on COPD.

Long-Acting Control Medications.

Corticosteroids are the mostpotent and effective anti-inflammatory

medications currently available. They are broadly effective in alleviating

symptoms, im-proving airway function, and decreasing peak flow variability.

Initially, the inhaled form is used. A spacer should be used with inhaled

corticosteroids and the patient should rinse the mouth after administration to

prevent thrush, a common complication of inhaled corticosteroid use. A systemic

preparation may be used to gain rapid control of the disease; to manage severe,

persistent asthma; to treat moderate to severe exacerbations; to accelerate

recovery; and to prevent recurrence (Dhand, 2000).

Cromolyn

sodium (Intal) and nedocromil (Tilade) are mild to moderate anti-inflammatory

agents that are used more com-monly in children. They also are effective on a

prophylactic basis to prevent exercise-induced asthma or in unavoidable

exposure to known triggers. These medications are contraindicated in acute

asthma exacerbations.

Long-acting beta2-adrenergic agonists are used with anti-inflammatory medications to control asthma symptoms, partic-ularly those that occur during the night. These agents are also effective for preventing exercise-induced asthma. Long-acting beta2-adrenergic agonists are not indicated for immediate relief of symptoms.

Methylxanthines

(theophylline [Slo-bid, Theo-24, Theo-Dur]) are mild to moderate

bronchodilators usually used in addition to inhaled corticosteroids, mainly for

relief of nighttime asthma symptoms. There is some evidence that theophylline

may have a mild anti-inflammatory effect (NHLBI, 1998).

Leukotriene

modifiers (inhibitors) or antileukotrienes are a new class of medications.

Leukotrienes are potent bronchocon-strictors that also dilate blood vessels and

alter permeability. Leukotriene inhibitors act by either interfering with

leukotriene synthesis or blocking the receptors where leukotrienes exert their

action (Boushey, Fick, Lazarus & Martin, 2000). At this time, they may

provide an alternative to inhaled corticosteroids for mild persistent asthma or

may be added to a regimen of inhaled corticosteroids in more severe asthma to

attain further control.

In

addition, combination products are also available (eg, albuterol/ipratropium

[Combivent]) and offer ease of use for the patient.

Quick-Relief Medications.

Short-acting beta-adrenergic agonistsare the medications of choice

for relieving acute symptoms and preventing exercise-induced asthma. They have

a rapid onset of action. Anticholinergics (eg, ipratropium bromide [Atrovent])

may bring added benefit in severe exacerbations, but they are used more

frequently in COPD patients.

MANAGEMENT OF ASTHMA EXACERBATION

Asthma

exacerbations are best managed by early treatment and education of the patient

(Expert Panel Report II, 1997). Quick-acting beta-adrenergic medications are

first used for prompt relief of airflow obstruction. Systemic corticosteroids

may be nec-essary to decrease airway inflammation in patients who fail to

re-spond to inhaled beta-adrenergic medications. In some patients, oxygen supplementation

may be required to relieve hypoxemia associated with a moderate to severe

exacerbation (Expert Panel Report II, 1997). Also, response to treatment may be

monitored by serial measurements of lung function.

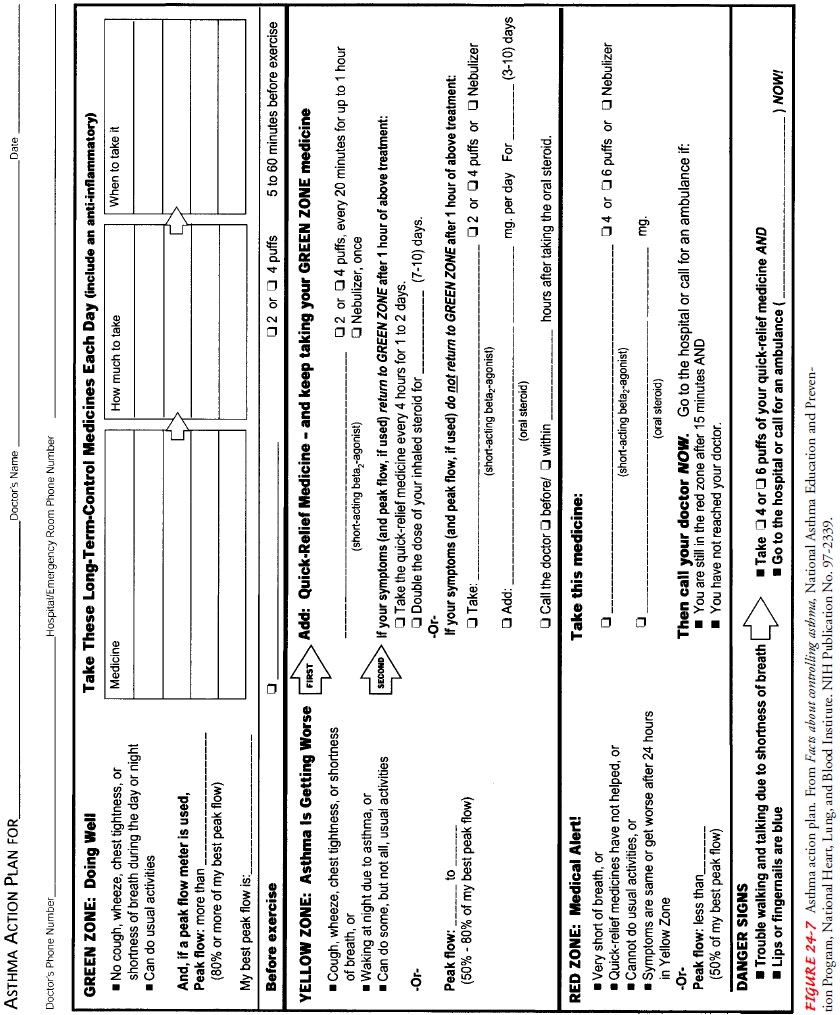

A

written action plan is the most useful tool for the patient (Fig. 24-7). This

helps to guide the patient in self-management strategies regarding an

exacerbation and also provides instruc-tions regarding recognition of early

warning signs of worsening asthma. Patient self-management and early recognition

of prob-lems lead to more efficient communication with health care providers

regarding an asthma exacerbation (Expert Panel Report II, 1997).

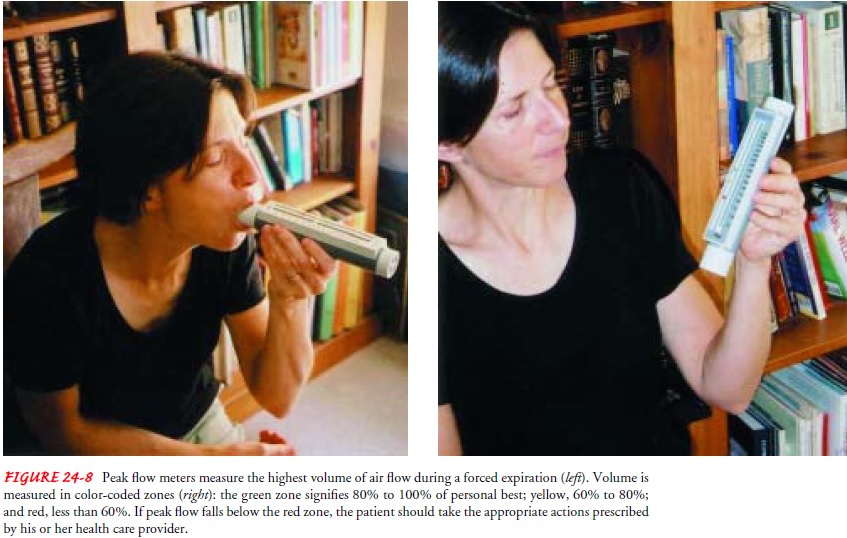

PEAK FLOW MONITORING

Peak

flow meters measure the highest airflow during a forced ex-piration (Fig. 24-8).

Daily peak flow monitoring is recommended for all patients with moderate or

severe asthma because it helps measure asthma severity and, when added to

symptom monitor-ing, indicates the current degree of asthma control. The

patient is instructed in the proper technique, particularly to give maxi-mal

effort. The “personal best” is determined after monitoring peak flows for 2 or

3 weeks after receiving optimal asthma ther-apy. The green (80% to 100% of

personal best), yellow (60% to 80%), and red (less than 60%) zones are

determined, and specific actions are delineated for each zone, enabling the

patient to mon-itor and manipulate his or her own therapy after careful

instruc-tion (Expert Panel Report II, 1997). This reinforces compliance,

independence, and self-efficacy (Reinke, 2000).

Nursing Management

The

immediate nursing care of the patient with asthma depends on the severity of

the symptoms. The patient may be treated suc-cessfully as an outpatient if

asthma symptoms are relatively mild, or he or she may require hospitalization

and intensive care for acute and severe asthma.

The

patient and family are often frightened and anxious be-cause of the patient’s

dyspnea. Thus, an important aspect of care is a calm approach. The nurse

assesses the patient’s respiratory status by monitoring the severity of

symptoms, breath sounds, peak flow, pulse oximetry, and vital signs. The nurse

obtains a history of allergic reactions to medications before administering

medications and identifies the patient’s current use of medica-tions. The nurse

administers medications as prescribed and mon-itors the patient’s responses to

those medications. Fluids may be administered if the patient is dehydrated, and

antibiotic agents may be prescribed if the patient has an underlying

respiratory in-fection. If the patient requires intubation because of acute

respi-ratory failure, the nurse assists with the intubation procedure,

continues close monitoring of the patient, and keeps the patient and family

informed about procedures.

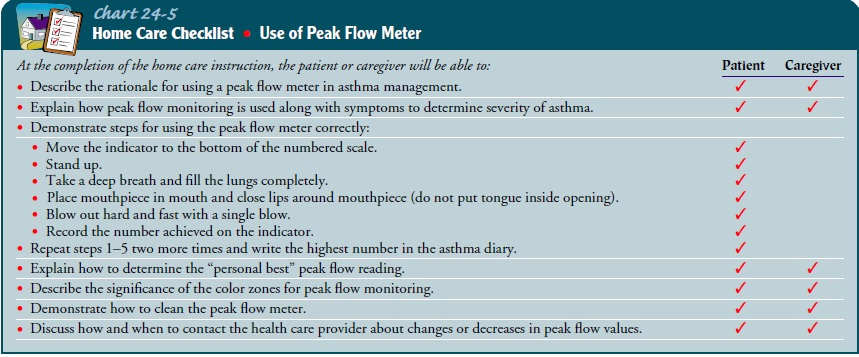

PROMOTING HOME AND COMMUNITY-BASED CARE

Teaching Patients Self-Care.

A major challenge is to implementbasic asthma management principles at the community level (Reinke, 2000). Key issues include education of health care providers, establishment of programs for asthma education (for patients and providers), use of outpatient follow-up care for pa-tients, and a focus on chronic management versus acute episodic care. The nurse is pivotal to achieving all of these objectives.

Patient

teaching is a critical component of care for the patient with asthma (Plaut,

2001). Multiple inhalers, different types of inhalers, antiallergy therapy,

antireflux medications, and avoid-ance measures are all integral for long-term

control. This com-plex therapy requires a patient–provider partnership to

determine the desired outcomes and to formulate a plan to achieve those

outcomes. The patient then carries out daily therapy as part of self-care management,

with input and guidance by the health care provider. Before a partnership can

be established, the patient needs to understand the following:

·

The nature of asthma as a chronic

inflammatory disease

·

The definition of inflammation and

bronchoconstriction

·

The purpose and action of each

medication

·

Triggers to avoid, and how to do so

·

Proper inhalation technique

·

How to perform peak flow monitoring

(Chart 24-5)

·

How to implement an action plan

·

When to seek assistance, and how to

do so

An assortment of excellent educational materials is available from the Expert Panel Report II (1997) and the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute.

The nurse should obtain current edu-cational materials for

the patient based on the patient’s diagno-sis, causative factors, educational

level, and cultural factors.

Continuing Care.

The

nurse who has contact with the patient inthe hospital, clinic, school, or

office uses the opportunity to as-sess the patient’s respiratory status and

ability to manage self-care to prevent serious exacerbations. The nurse

emphasizes adherence to the prescribed therapy, preventive measures, and the

need to keep follow-up appointments with the primary health care provider. A

home visit to assess the home environment for aller-gens may be indicated for

the patient with recurrent exacerba-tions. The nurse refers the patient to

community support groups. In addition, the nurse reminds the patient and family

about the importance of health promotion strategies and recommended health

screening.

Related Topics