Chapter: Environmental Biotechnology: Phytotechnology and Photosynthesis

Carbon sequestration

Carbon sequestration

Their use as a carbon sink is a simpler process, only requiring the

algae them-selves. However, even as a functional algal monoculture, just as

with the joint algal/bacterial bioprocessing for effluents, without external

intervention to limit the standing burden of biomass within the bioreactor,

reduced efficiency and, ultimately, system collapse is inevitable.

In nature, huge amounts of

many elements are held in global reservoirs, reg-ulated by biogeochemical

cycles, driven by various interrelated biological and chemical systems. For

carbon, a considerable mass is held in organic and inor-ganic oceanic stores,

with the seas themselves being dynamic and important component parts of the

planetary carbon cycle. Marine phytoplankton utilise car-bon dissolved in the

water during photosynthesis, incorporating it into biomass and simultaneously

increasing the inflow gradient from the atmosphere. When these organisms die,

they sink, locking up this transient carbon and taking it out of the upper

oceanic ‘fast’ cycle into the ‘slow’ cycle, which is bounded by long-term

activities within the deep ocean sediments. In this respect, the system may be

likened to a biological sequestration pump, effectively removing atmo-spheric

CO2 from circulation within the biosphere on an extended basis. The number,

mass and extent of phytoplankton throughout the world’s seas thus pro-vide a

carbon-buffering capacity on a truly enormous scale, the full size of which has

only really become apparent within the last 10 – 15 years, with the benefit of

satellite observation.

In the century since its

effectiveness as a means of trapping heat in the atmo-sphere was first

demonstrated by the Swedish scientist, Svante Arrhenius, the importance of

reducing the global carbon dioxide emissions has come to be widely appreciated.

The increasing quantities of coal, oil and gas that are burnt for energy has

led to CO2 emissions worldwide becoming more than 10 times higher than they

were in 1900 and there is over 30% more CO2 in the air, cur-rently around 370

parts per million (ppm), than before the Industrial Revolution. Carbon dioxide

is responsible for over 80% of global warming and according to analysis of

samples of the Antarctic ice, the world today has higher levels of greenhouse

gases than at any time in the past 400 000 years. The UN Intergov-ernmental

Panel on Climate Change has warned that immediate action is required to prevent

further atmospheric increases above today’s level. In the absence of swift and

effective measures to control the situation, by 2100 they predict that carbon

dioxide concentrations will rise to 550 ppm on the basis of their lowest

emission model, or over 830 ppm in the highest.

In 1990, over 95% of the

western industrialised nations’ emissions resulted from burning fossil fuels

for energy, with the 25% of the world’s population who live in these countries

consuming nearly 80% of the energy produced globally. Unsurprisingly, energy

industries account for the greatest share (36%) of carbon dioxide emissions, a

large 1000 Megawatt coal-fired power station releases some-thing in the region

of 5 1/2 million tonnes of CO2 annually.

Clearly, the current focus on reducing fossil fuel usage, and on minimising the

emissions of car-bon dioxide to atmosphere, is important. In one sense, the

most straightforward solution to the problem is simply to stop using fossil

fuels altogether. However, this is a rather simplistic view and just too impractical.

While great advances have been made in the field of renewable energy, a

wholesale substitution for gas, coal and oil is not possible at this time if

energy usage is to continue at an unabated rate. The potential role of existing

nonfossil fuel technology to bridge the gap between the current status quo and

a future time, when renewables meet the needs of mankind, is a vital one.

However, it is ridiculous to pretend that this can be achieved overnight,

unless the ‘global village’ really is to consist of just so many mud huts.

In many respects, here is

another case where, if we cannot do the most good, then perhaps we must settle

for doing the least harm and the application of phytotechnology stands as one

very promising means by which to achieve this goal. The natural contribution of

algal photosynthesis to carbon sequestration has already been alluded to and

the use of these organisms in an engineered system to reduce CO2

releases, simply capitalises on this same inherent potential in an unaltered

way.

There have been attempts to

commercialise the benefits of algae as carbon sinks. In the early 1990s, two

prototype systems were developed in the UK, aimed at the reduction of CO2

emissions from various forms of existing combus-tion processes. The BioCoil was

a particularly interesting integrated approach, removing carbon dioxide from

generator emissions and deriving an alternative fuel source in the process. The

process centred on the use of unicellular algal species in a narrow,

water-containing, spiral tube made of translucent polymer, through which the

exhaust gases from the generator was passed. The carbon dioxide rich waters

provided the resident algal with optimised conditions for photosynthesis which

were further enhanced by the use of additional artificial light. The algal

biomass recovered from the BioCoil reactor was dried, and being unicellular,

the effective individual particle size tended to the dimensions of diesel

injection droplets, which, coupled with an energy value roughly equiva-lent to

medium grade bituminous coal at 25 MJ/kg, makes it ideal for use in a suitable

engine without further modification. Despite early interest, the system does

not appear to have been commercially adopted or developed further.

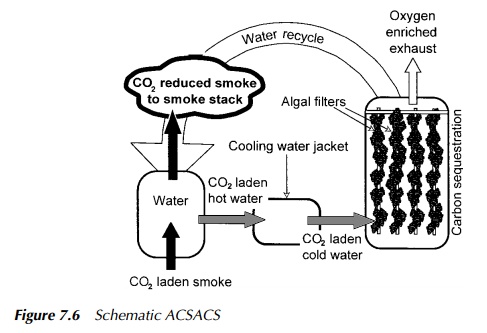

Around the same time, another

method was also suggested by one of the authors. In this case, it was his

intent specifically to deal with the carbon diox-ide produced when biogas, made

either at landfill sites or anaerobic digestion plants, was flared or used for

electricity generation. Termed the algal cultiva-tion system and carbon sink

(ACSACS), it used filamentous algae, growing as attached biofilter elements on

a polymeric lattice support. CO2 rich exhaust gas

was passed into the bottom of a bioreactor vessel, containing the

plastic filter elements in water, and allowed to bubble up to the surface

through the algal strands as shown in Figure 7.6.

Again, this approach to

carbon sequestration was based on enhanced intra-reactor photosynthesis, the

excess algal biomass being harvested to ensure the ongoing viability of the

system, with the intention of linking it into a compost-ing operation to

achieve the long-term carbon lock-up desired. The ACSACS though performing well

at both bench and small pilot scale, never attained indus-trial adoption though

remaining an interesting possible adjunct to the increasing demand for methane

flaring or utilisation at landfills.

A similar idea emerged again

recently, with a system being developed by Ohio University, which, in a perfect

example of selecting an organism from an extreme environment to match the

demands of a particular manmade situation, utilises thermophilic algae from hot

springs in Yellowstone National Park. In this process, which has received a $1

million grant from the US Department of Energy, smoke from power stations is

diverted through water to permit some of the CO2 to be absorbed and

the hot, carbonated water produced then flows through an algal filter formed on

vertical nylon screens.

This design, which is

essentially similar to the earlier ACSACS, enables the largest possible algal

population per unit volume to be packed into the filter unit, though like the

previously described HRAP, light is a limiting factor, since direct sunlight

will only penetrate through a few feet of such an arrangement. However, it is

claimed that these carbon biofilters could remove up to 20% of the carbon

dioxide, which would, of course, otherwise be released to atmosphere. This makes

solving the problem something of a priority. One solution involves the use of a

centralised light collector, connected to a series of fibre-optic cables linked

to diffusers within the vessels to provide adequate illumination within the

filters. An alternative approach has been put forward, using large artificial

lakes, but this would require a much larger land bank to produce the same

effect, since they would have to be very shallow by comparison. It has also

been suggested that cooling the carbonated water first, a feature of both the

BioCoil and ACSACS, would allow normal mesophilic algae to be used, which take

up CO2 more efficiently. Whether this technique will prove any more

successful in gaining industrial or commercial acceptance than either of the

earlier British systems remains to be seen.

Related Topics