Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: Eating Disorders

Bulimia Nervosa

Bulimia

Nervosa

Definition

The

salient behavioral disturbance of bulimia nervosa is the occurrence of episodes

of binge-eating. During these episodes, the individual consumes an amount of

food that is unusually large considering the circumstances under which it was

eaten. Although this is a useful definition and conceptu-ally reasonably clear,

it can be operationally difficult to distin-guish normal overeating from a

small episode of binge-eating. Indeed, the available data do not suggest that

there is a sharp dividing line between the size of binge-eating episodes and

the size of other meals. On the other hand, while the border between normal and

abnormal eating may not be a sharp one, both patients’ reports and laboratory

studies of eating behavior clearly indicate that, when binge-eating, patients

with bulimia nervosa do indeed consume larger than normal amounts of food.

Episodes

of binge-eating are associated, by definition, with a sense of loss of control.

Once the eating has begun, the in-dividual feels unable to stop until an

excessive amount has been consumed. This loss of control is only subjective, in

that most individuals with bulimia nervosa will abruptly stop eating in the

midst of a binge episode if interrupted, for example, by the unex-pected

arrival of a roommate.

After overeating, individuals with bulimia nervosa en-gage in some form of inappropriate behavior in an attempt to avoid weight gain. Most patients who present to eating disorders clinics with this syndrome report self-induced vomiting or the abuse of laxatives. Other methods include misusing diuretics, fasting for long periods and exercising extensively after eating binges.

The

DSM-IV-TR criteria require that the overeating epi-sodes and the compensatory

behaviors both occur at least twice a week for 3 months to merit a diagnosis of

bulimia nervosa. This criterion, although useful in preventing the diagnostic

label from being applied to individuals who only rarely have difficulty with

binge-eating, is clearly an arbitrary one.

Criterion

D in the DSM-IV-TR definition of bulimia ner-vosa requires that individuals

with bulimia nervosa exhibit an over concern with body shape and weight. That

is, they tend to base much of their self-esteem on how much they weigh and how

slim they look.

Finally,

in the DSM-IV-TR nomenclature, the diagnosis of bulimia nervosa is not given to

individuals with anorexia ner-vosa. Individuals with anorexia nervosa who

recurrently engage in binge-eating or purging behavior should be given the

diag-nosis of anorexia nervosa, binge-eating/purging subtype, rather than an

additional diagnosis of bulimia nervosa.

In

DSM-IV-TR, a subtyping scheme was introduced for bulimia nervosa in which

patients are classed as having either the purging or the nonpurging type of

bulimia nervosa. This scheme was introduced for several reasons. First, those

indi-viduals who purge are at greater risk for the development of fluid and

electrolyte disturbances such as hypokalemia. Sec-ondly, data suggest that

individuals with the nonpurging type of bulimia nervosa weigh more and have

less psychiatric illness compared with those with the purging type. Finally,

most of the published literature on the treatment of bulimia nervosa has been

based on studies of individuals with the purging type of this disorder.

Epidemiology

Soon

after bulimia nervosa was recognized as a distinct dis-order, surveys indicated

that many young women reported problems with binge-eating, and it was suggested

that the syn-drome of bulimia nervosa was occurring in epidemic propor-tions.

Later careful studies have found that although binge-eating is frequent, the

full-blown disorder of bulimia nervosa is much less common, probably affecting

1 to 2% of young women in the USA. Although sufficient research data do not

exist to pinpoint specific epidemiological trends in the occur-rence of bulimia

nervosa, research suggests that women born after 1960 have a higher risk for

the illness than those born before 1960.

Evidence

suggests an important role of sociocultural in-fluences in the development of

bulimia nervosa. For example, the frequency of the disorder has been reported

to be increasing among immigrants to the USA and UK from nonWestern coun-tries

(Hsu, 1990). Although the rate of the disorder appears to be lower among

nonwhite and nonWestern cultures, the frequency of bulimia nervosa has been

reported to be increasing among these groups, especially among the higher

socioeconomic classes. Sur-prisingly, several epidemiological and clinical

studies in the USA found no relationship between bulimia nervosa and social

class (Kendler et al., 1991).

Among

patients with bulimia nervosa who are seen at eat-ing disorders clinics, there

is an increased frequency of anxiety and mood disorders, especially major

depressive disorder and dysthymic disorder, of drug and alcohol abuse, and of

personal-ity disorders. It is not certain whether this comorbidity is also

observed in community samples or whether it is a characteristic of individuals

who seek treatment.

Etiology

As in the

case of anorexia nervosa, the etiology of bulimia ner-vosa is uncertain.

Several factors clearly predispose individuals to the development of bulimia

nervosa, including being an ado-lescent girl or young adult woman. A personal

or family history of obesity and of mood disturbance also appears to increase

risk. Twin studies have suggested that inherited factors are related to the

risk of developing bulimia nervosa, but what these factors are and how they

operate are unclear.

Many of

the same psychosocial factors related to the de-velopment of anorexia nervosa

are also applicable to bulimia ner-vosa, including the influence of cultural

esthetic ideals of thinness and physical fitness. Similarly, bulimia nervosa

primarily affects women; the ratio of men to women is approximately 1 : 10. It

also

occurs

more frequently in certain occupations (e.g., modeling) and sports (e.g.,

wrestling, running).

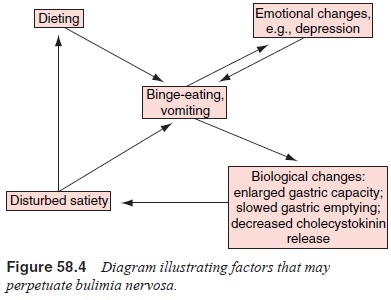

Although

not proven, it seems likely that several fac-tors serve to perpetuate the

binge-eating once it has begun (Figure 58.4 First, most individuals with

bulimia nervosa, be-cause of both their concern regarding weight and their

worry about the effect of the binge-eating, attempt to restrict their food

intake when they are not binge-eating. The psychological and physiological restraint

that is thereby entailed presumably makes additional binge-eating more likely.

Secondly, even if mood disturbance is not present at the outset, individuals

be-come distressed about their inability to control their eating, and the

resultant lowering of self-esteem contributes to dis-turbances of mood and to a

reduced ability to control impulses to overeat. In addition,

cognitive–behavioral theories empha-size the role of rigid rules regarding food

and eating, and the distorted and dysfunctional thoughts that are similar to

those seen in anorexia nervosa. Interpersonal theories also impli-cate

interpersonal stressors as a primary factor in triggering binge-eating. There

is no evidence to suggest that a particular personality structure is

characteristic of women with bulimia nervosa.

There are

also indications that bulimia nervosa is accom-panied by physiological

disturbances that disrupt the develop-ment of satiety during a meal and

therefore increase the likeli-hood of binge-eating. These disturbances include

an enlarged stomach capacity, a delay in stomach emptying and a reduction in

the release of cholecystokinin, a peptide hormone secreted by the small

intestine during a meal that normally plays a role in terminating eating

behavior. All these abnormalities appear to predispose the individual to

overeat and therefore to perpetuate the cycle of binge-eating.

It has been suggested that childhood sexual abuse is a specific risk factor for the development of bulimia nervosa. Sci-entific support for this hypothesis is weak. The best studies to date have found that compared with women without psychiatric illness, women with bulimia nervosa do indeed report increased frequencies of sexual abuse. However, the rates of abuse are similar to those found in other psychiatric disorders and occur in a minority of women with bulimia nervosa. Thus, while early abuse may predispose an individual to psychiatric problems gen-erally, it does not appear to lead specifically to an eating disorder and most patients with bulimia nervosa do not have histories of sexual abuse

Pathophysiology

In a

small fraction of individuals, bulimia nervosa is associated with the

development of fluid and electrolyte abnormalities that result from the

self-induced vomiting or the misuse of laxatives or diuretics. The most common

electrolyte disturbances are hy-pokalemia, hyponatremia and hypochloremia.

Patients who lose substantial amounts of stomach acid through vomiting may

be-come slightly alkalotic; those who abuse laxatives may become slightly

acidotic.

There is

an increased frequency of menstrual disturbances such as oligomenorrhea among

women with bulimia nervosa. Sev-eral studies suggest that the

hypothalamic–pituitary–gonadal axis is subject to the same type of disruption

as is seen in anorexia ner-vosa but that the abnormalities are much less

frequent and severe.

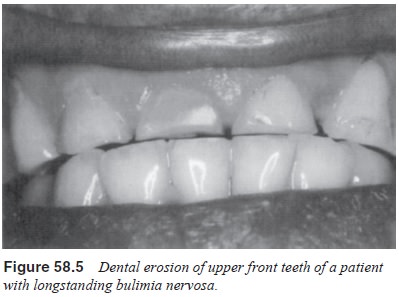

Patients

who induce vomiting for many years may develop dental erosion, especially of

the upper front teeth (Figure 58.5). The mechanism appears to be that stomach

acid softens the enamel, which in time gradually disappears so that the teeth

chip more easily and can become reduced in size. Some patients de-velop

painless salivary gland enlargement, which is thought to represent hypertrophy

resulting from the repeated episodes of binge-eating and vomiting. The serum

level of amylase is some-times mildly elevated in patients with bulimia nervosa

because of increased amounts of salivary amylase.

Most

patients with bulimia nervosa have surprisingly few gastrointestinal

abnormalities. As indicated earlier, it appears that the disorder is associated

with an enlarged gastric capacity and delayed gastric emptying, but these

abnormalities are not so severe as to be detectable on routine clinical

examination. Poten-tially life-threatening complications such as an esophageal

tear or gastric rupture occur, but fortunately rarely.

The

longstanding use of syrup of ipecac to induce vomit-ing can lead to absorption

of some of the alkaloids and to perma-nent damage to nerve and muscle.

Related Topics