Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: Eating Disorders

Anorexia Nervosa

Anorexia

Nervosa

Definition

The

DSM-IV-TR criteria require the individual to be significantly underweight for

age and height. Although it is not possible to set a single weight loss

standard that applies equally to all individu-als, DSM-IV-TR provides a

benchmark of 85% of the weight con-sidered normal for age and height as a

guideline. Despite being of an abnormally low body weight, individuals with

anorexia ner-vosa are intensely afraid of gaining weight and becoming fat, and

remarkably, this fear typically intensifies as the weight falls.

DSM-IV-TR

criterion C requires a disturbance in the per-son’s judgment about his or her

weight or shape. For example, despite being underweight, individuals with

anorexia nervosa often view themselves or a part of their body as being too

heavy. Typically, they deny the grave medical risks engendered by their

semistarvation and place enormous psychological importance on whether they have

gained or lost weight. For example, some-one with anorexia nervosa may feel

intensely distressed if her or his weight increases by half a pound. Finally,

criterion D requires that women with anorexia nervosa be amenorrheic.

The

DSM-IV-TR criteria for anorexia nervosa are gener-ally consistent with recent

definitions and descriptions of this ill-ness. In addition, in DSM-IV-TR, a new

subtyping scheme was introduced. DSM-IV-TR suggests that individuals with

anorexia nervosa be classed as having one of two variants, either the

binge-eating/purging type or the restricting type. Individuals with the

re-stricting type of anorexia nervosa do not engage regularly in either

binge-eating or purging and, compared with individuals with the binge-eating/purging

form of the disorder, are not as likely to abuse alcohol and other drugs,

exhibit less mood lability and are less ac-tive sexually. There are also

indications that the two subtypes may differ in their response to

pharmacological intervention.

Epidemiology

Anorexia nervosa is a relatively rare illness. Even among high-risk groups, such as adolescent girls and young women, the preva-lence of strictly defined anorexia nervosa is only about 0.5%. The prevalence rates of partial syndromes are substantially higher. Despite the infrequent occurrence of anorexia nervosa, most studies suggest that its incidence has increased significantly dur-ing the last 50 years, a phenomenon usually attributed to changes in cultural norms regarding desirable body shape and weight Anorexia nervosa usually affects women; the ratio of men to women is approximately 1 : 10 to 1 : 20. Anorexia nervosa oc-curs primarily in industrialized and affluent countries and some data suggest that even within those countries, anorexia nervosa is more common among the higher socioeconomic classes. Some occupations, such as ballet dancing and fashion modeling, appear to confer a particularly high risk for the development of anorexia nervosa. Thus, anorexia nervosa appears more likely to develop in an environment in which food is readily available but in which, for women, being thin is somehow equated with higher or special achievement.

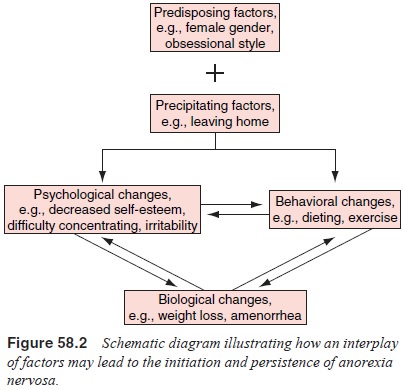

Etiology

At

present, the etiology of anorexia nervosa is fundamentally unknown. However,

from several sources, such as the epidemio-logical data just reviewed, it is

possible to identify risk factors whose presence increases the likelihood of

anorexia nervosa. It is also possible to describe the course and complications

of the syndrome and to suggest interactions between features of the dis-order,

for example, between malnutrition and psychiatric illness. Thus, as indicated

in Figure 58.2, the difficulties that lead to the development of anorexia

nervosa may be distinct from the forces that intensify the symptoms and

perpetuate the illness once it has begun.

Genetic and Twin Studies

Anorexia nervosa occurs more frequently in biological relatives of patients who present with the disorder. The prevalence rate of anorexia nervosa among sisters of patients is estimated to be approximately 6%; the morbid risk among other relatives ranges from 2 to 4%. Some evidence for a genetic component in the etiol-ogy of anorexia nervosa comes from twin studies, which reported substantially higher concordance rates for monozygotic than for dizygotic twin pairs (Klump et al., 2001). However, conclusive data for genetic transmission of the disorder are not yet available

Family Studies

Individual

psychiatric disorders in parents, dysfunctional fam-ily relationships and

impaired family interaction patterns have been implicated in the etiology of

anorexia nervosa. Mothers of individuals with anorexia nervosa are often

described as over-protective, intrusive, perfectionistic and fearful of

separation; fathers are described as withdrawn, passive, emotionally

con-stricted, obsessional, moody and ineffectual. Family systems theorists have

suggested that impaired family interactions such as pathological enmeshment,

rigidity, overprotectiveness, and difficulties confronting and resolving

conflicts are central fea-tures of anorexic pathology. However, few empirical

studies have been conducted to date, particularly studies that also examine

psychiatrically or medically ill comparison groups. Therefore, the precise role

of the family in the development and course of anorexia nervosa, although

undoubtedly important, has not been clearly delineated.

Psychosocial Factors

The

increased prevalence of anorexia nervosa has been connected to the current

emphasis in contemporary Western society on an unrealistically thin appearance

in women. There is substantial evidence that a desire to be slim is common

among middle- and upper-class white women and that this emphasis on slimness

has increased significantly during the past several decades. In the USA,

anorexia nervosa develops much more frequently in white adolescents than in

adolescents from other racial groups. It has been suggested that a variety of

characteristics may protect African-American girls from having eating

disorders, including more acceptance of being overweight, more satisfaction

with their body image and less social pressure regarding weight.

It has

also been suggested that the emphasis of contem-porary Western society on

achievement and performance in women, which is a shift from the more

traditional emphasis on deference, compliance and unassertiveness, has left

many young women vulnerable to the development of eating disorders such as

anorexia nervosa. These multiple and contradictory role demands are embodied

within the modern concept of a superwoman who performs all of the expected

roles (e.g., is competent, ambitious and achieving, yet also feminine,

nurturing and sexual) and, in addition, devotes considerable attention to her appearance

(Gordon, 1990).

Psychodynamic Factors

Various

psychoanalytic theories have been postulated (e.g., de-fense against fantasies

of oral impregnation; underlying deficits in the development of object

relations; deficits in self-structure), but such hypotheses are difficult to

verify. Bruch (1973, 1982) suggested that anorexia nervosa stems from failures

in early at-tachment, attempts to cope with underlying feelings of

ineffec-tiveness and inadequacy, and an inability to meet the demands of adolescence

and young adulthood. These ideas, as well as her conceptualization that the

single-minded focus on losing weight in anorexia nervosa is the concrete

manifestation of a struggle to achieve a sense of identity, purpose,

specialness and control, are compelling and clinically useful.

Cognitive–behavioral theo-ries emphasize the distortions and dysfunctional

thoughts (e.g., dichotomous thinking) that may stem from various causal

fac-tors, all of which eventually focus on the belief that it is essential to be

thin.

Although

the existence of a specific predisposing person-ality style has not been

conclusively documented, certain traits have commonly been reported among women

with anorexia nervosa. Women hospitalized for anorexia nervosa have greater

self-discipline, conscientiousness and emotional caution than women

hospitalized for bulimia nervosa and women with no eat-ing disorders. In

addition, even after they have recovered from their illness, women who have had

anorexia nervosa tend to avoid risks and to exhibit high levels of caution in

emotional expression and strong compliance with rules and moral standards.

Developmental Factors

Because

anorexia nervosa typically begins during adolescence, developmental issues are

thought to play an important etiologi-cal role. Critical challenges at this

time of life include the need to establish independence, a well-defined

personal identity, ful-filling relationships, and clear values and principles

to govern one’s life. Family struggles, conflicts regarding sexuality and

pressures regarding increased heterosexual contact are also com-mon. However,

it is not clear that difficulties over these issues are more salient for

individuals who will develop anorexia nervosa than for other adolescents.

Depression has been implicated as a nonspecific risk factor, and higher levels

of depressive symptoms as well as insecurity, anxiety and self-consciousness

have been documented in adolescent girls in comparison with adolescent boys.

Similarly, the progression of physical and sexual matura-tion and the

concomitant increase in women’s percentage of body fat may have a substantial

impact on the self-image of adolescent girls, particularly because the

relationship between self-esteem and satisfaction with physical appearance and

body characteris-tics is stronger in women than in men.

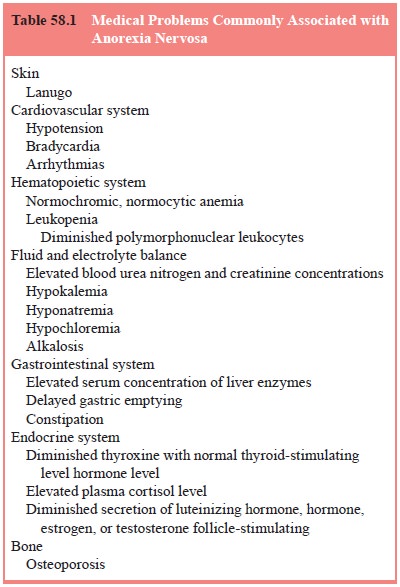

Pathophysiology

An

impressive array of physical disturbances has been docu-mented in anorexia

nervosa and the physiological bases of many are understood (Table 58.1). Most

of these physical disturbances appear to be secondary consequences of

starvation, and it is not clear whether or how the physiological disturbances

described here contribute to the development and maintenance of the

psy-chological and behavioral abnormalities characteristic of ano-rexia

nervosa. The remainder of this section briefly describes the major physical

abnormalities of anorexia nervosa and what is understood about their etiology.

The

central nervous system is clearly affected. Computed tomography has

demonstrated that individuals with anorexia ner-vosa have enlarged ventricles,

an abnormality that improves with weight gain. The cerebrospinal fluid

concentrations of a variety of neurotransmitters and their metabolites are

altered in under-weight patients with anorexia nervosa and tend to normalize as

weight is restored. An intriguing exception may be the serotonin metabolite

5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid, which has been reported to be elevated in the

cerebrospinal fluid of patients with anorexia nervosa after they have achieved

a normal or near-normal weight. Kaye (1997) has suggested that the elevated

5-hydroxyindoleace-tic acid levels may reflect a serotoninergic abnormality

that is tied to the obsessional traits often observed in anorexia nervosa.

Some of

the most striking physiological alterations in ano-rexia nervosa are those of

the hypothalamic–pituitary–gonadal axis. In women, estrogen secretion from the

ovaries is markedly reduced, accounting for the occurrence of amenorrhea. In

analo-gous fashion, testosterone production is diminished in men with anorexia

nervosa. The decrease in gonadal steroid production is due to a reduction in

the pituitary’s secretion of the gonadotropins luteinizing hormone and

follicle-stimulating hormone, which in turn is secondary to diminished release

of gonadotropin-releasing

hormone

from the hypothalamus. Therefore, the amenorrhea of anorexia nervosa is

properly viewed as a type of hypothalamic amenorrhea. It is of interest that in

a significant minority amenor-rhea begins before substantial weight loss has

occurred, suggest-ing that factors other than malnutrition, such as

psychological distress, contribute significantly to the disruption of the

repro-ductive endocrine system.

In an

adult with anorexia nervosa, the status of the hy-pothalamic–pituitary–gonadal

axis resembles that of a pubertal or prepubertal child – the secretion of

estrogen or testosterone, of luteinizing hormone and follicle-stimulating

hormone and of go-nadotropin-releasing hormone is reduced. This endocrinological

picture may be contrasted with that of postmenopausal women who have a similar

reduction in estrogen secretion but who, un-like women with anorexia nervosa,

show increased pituitary go-nadotropin secretion. Furthermore, even the

circadian patterns of luteinizing hormone and follicle-stimulating hormone

secretion in adult women with anorexia nervosa closely resemble the pat-terns

normally seen in pubertal and prepubertal girls. Although similar abnormalities

are also seen in other forms of hypotha-lamic amenorrhea and are therefore not

specific to anorexia ner-vosa, it is nonetheless striking that this syndrome is

accompanied by a physiological arrest or regression of the reproductive

endo-crine system.

The

functioning of other hormonal systems is also disrupted in anorexia nervosa,

although typically not as profoundly as is the reproductive axis. Presumably as

part of the metabolic response to semistarvation, the activity of the thyroid

gland is reduced Plasma thyroxine levels are somewhat diminished, but the

plasma level of the pituitary hormone and thyroid-stimulating hormone is not

elevated. The activity of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis is increased,

as indicated by elevated plasma levels of cortisol and by resistance to

dexamethasone suppression. The regulation of vasopressin (antidiuretic hormone)

secretion from the posterior pituitary is disturbed, contributing to the

development of partial diabetes insipidus in some individuals.

Anorexia

nervosa is often associated with the develop-ment of leukopenia and of a

normochromic, normocytic anemia of mild to moderate severity. Surprisingly,

leukopenia does not appear to result in a high vulnerability to infectious

illnesses. Se-rum levels of liver enzymes are sometimes elevated, particularly

during the early phases of refeeding, but the synthetic function of the liver

is rarely seriously impaired so that the serum albu-min concentration and the

prothrombin time are usually within normal limits. Serum cholesterol levels are

sometimes elevated in anorexia nervosa, although the basis of this abnormality

re-mains obscure. In some patients, self-imposed fluid restriction and

excessive exercise produce dehydration and elevations of se-rum creatinine and

blood urea nitrogen. In others, water loading may lead to hyponatremia. The

status of serum electrolytes is a reflection of the individual’s salt and water

intake and the nature and the severity of the purging behavior. A common

pattern is hypokalemia, hypochloremia and mild alkalosis resulting from frequent

and persistent self-induced vomiting.

It has

become clear that individuals with anorexia ner-vosa have decreased bone

density compared with age- and sex-matched peers and, as a result, are at

increased risk for fractures. Low levels of estrogen, high levels of cortisol

and poor nutrition have been cited as risk factors for the development of

reduced bone density in anorexia nervosa. Theoretically, estrogen treat-ment

might reduce the risk of osteoporosis in women who are chronically amenorrheic

because of anorexia nervosa, but con-trolled studies indicate that this

intervention is of limited, if any, benefit.

Abnormalities

of cardiac function include bradycardia and hypotension, which are rarely

symptomatic. The pump function of the heart is compromised, and congestive

heart failure occa-sionally develops in individuals during overly rapid

refeeding. The electrocardiogram shows sinus bradycardia and a number of

nonspecific abnormalities. Arrhythmias may develop, often in association with

fluid and electrolyte disturbances. It has been suggested that significant

prolongation of the QT interval may be a harbinger of life-threatening

arrhythmias in some individ-uals with anorexia nervosa, but this has not been

conclusively demonstrated.

The

motility of the gastrointestinal tract is diminished, leading to delayed

gastric emptying and contributing to com-plaints of bloating and constipation.

Rare cases of acute gastric dilatation or gastric rupture, which is often

fatal, have been re-ported in individuals with anorexia nervosa who consumed

large amounts of food when binge-eating.

As

already noted, virtually all of the physiological abnor-malities described in

individuals with anorexia nervosa are also seen in other forms of starvation,

and most improve or disappear as weight returns to normal. Therefore, weight

restoration is essen-tial for physiological recovery. More surprisingly,

perhaps, weight restoration is believed to be essential for psychological

recovery as well. Accounts of human starvation amply document the pro-found

impact of starvation on mental health. Starving individuals lose their sense of

humor, their interest in friends and family fadesand mood generally becomes

depressed. They may develop pe-culiar behavior similar to that of patients with

anorexia nervosa, such as hoarding food or concocting bizarre food

combinations. If starvation disrupts psychological and behavioral functioning

in normal individuals, it presumably does so as well in those with anorexia

nervosa. Thus, correction of starvation is a prerequisite for the restoration

of both physical and psychological health.

Diagnosis and Differential Diagnosis

Phenomenology

Anorexia

nervosa often begins innocently. Typically, an adoles-cent girl or young woman

who is of normal weight or, perhaps, a few pounds overweight decides to diet.

This decision may be prompted by an important but not extraordinary life event,

such as leaving home for camp, attending a new school, or a casual unflattering

remark by a friend or family member. Initially, the dieting seems no different

from that pursued by many young women, but as weight falls, the dieting

intensifies. The restric-tions become broader and more rigid; for example,

desserts may first be eliminated, then meat, then any food that is thought to

contain fat. The person becomes increasingly uncomfortable if she is seen

eating and avoids meals with others. Food seems to assume a moral quality so

that vegetables are viewed as “good” and anything with fat is “bad”. The

individual has idiosyncratic rules about how much exercise she must do and

when, where and how she can eat.

Food

avoidance and weight loss are accompanied by a deep and reassuring sense of

accomplishment, and weight gain is viewed as a failure and a sign of weakness.

Physical activity, such as running or aerobic exercise, often increases as the

dieting and weight loss develop. Inactivity and complaints of weakness usually

occur only when emaciation has become extreme. The person becomes more serious

and devotes little effort to anything but work, dieting and exercise. She may

become depressed and emotionally labile, socially withdrawn and secretive and

she may lie about her eating and her weight. Despite the profound distur-bances

in her view of her weight and of her calorie needs, reality testing in other

spheres is intact, and the person may continue to function well in school or at

work. Symptoms usually persist for months or years until, typically at the

insistence of friends or family, the person reluctantly agrees to see a physician.

In

general, anorexia nervosa is not difficult to recognize. Uncertainty

surrounding the diagnosis sometimes occurs in young adolescents, who may not

clearly describe a drive for thin-ness and the fear of becoming fat. Rather,

they may acknowl-edge only a vague concern about consuming certain foods and an

intense desire to exercise. It can also be difficult to elicit the distorted

view of shape and weight (criterion C) from patients who have had anorexia

nervosa for many years. Such individu-als may state that they realize they are

too thin and may make superficial efforts to gain weight, but they do not seem

particu-larly concerned about the physical risks or deeply committed to

increasing their calorie consumption.

Assessment

Special Issues in Psychiatric Examination and History

In

assessing individuals who may have anorexia nervosa, it is important to obtain

a weight history including the individual’s highest and lowest weights and the

weight he or she would like to be now. For women, it is useful to know the

weight at which menstruation last occurred, because it provides an indi-cation

of what weight is normal for that individual. The patient should be asked to

describe a typical day’s food intake and any food restrictions and dietary

practices such as vegetarian-ism. The psychiatrist should ask whether the

patient ever loses control over eating and engages in binge-eating and, if so,

the amounts and types of food eaten during such episodes. The use of

self-induced vomiting, laxatives, diuretics, enemas, diet pills, and syrup of

ipecac to induce vomiting should also be queried.

Probably

the greatest problem in the assessment of pa-tients with anorexia nervosa is

their denial of the illness and their reluctance to participate in an

evaluation. A straightforward but supportive and nonconfrontational style is

probably the most useful approach, but it is likely that the patient will not

acknowl-edge significant difficulties in eating or with weight and will

ra-tionalize unusual eating or exercise habits. It is therefore helpful to

obtain information from other sources such as the patient’s family.

Physical Examination and Laboratory Findings

The

patient should be weighed, or a current weight should be obtained from the

patient’s general physician. Blood pressure, pulse and body temperature are

often below the lower limit of normal. On physical examination, lanugo, a fine,

downy hair nor-mally seen in infants, may be present on the back or the face.

The extremities are frequently cold and have a slight red–purple color

(acrocyanosis). Edema is rarely observed at the initial pres-entation but may

develop transiently during the initial stages of refeeding.

The basis

for laboratory abnormalities is presented in the earlier section on

pathophysiology. Common findings are a mild to moderate normochromic,

normocytic anemia and leukope-nia, with a deficit in polymorphonuclear

leukocytes leading to a relative lymphocytosis. Elevations of blood urea

nitrogen and serum creatinine concentrations may occur because of dehydra-tion,

which can also artificially elevate the hemoglobin and he-matocrit. A variety

of electrolyte abnormalities may be observed, reflecting the state of hydration

and the history of vomiting and diuretic and laxative abuse. Serum levels of liver

enzymes are usually normal but may transiently increase during refeeding.

Cholesterol levels may be elevated.

The

electrocardiogram typically shows sinus bradycardia and, occasionally, low QRS

voltage and a prolonged QT interval; a variety of arrhythmias have also been

described.

Differences in Presentation

The

symptoms of anorexia nervosa are remarkably homogene-ous, and differences

between patients in clinical manifestations are fewer than in most psychiatric

illnesses. As described before, younger patients may not express verbally the

characteristic fear of fatness or the overconcern with shape and weight, and

some patients with longstanding anorexia nervosa may express a desire to gain

weight but be unable to make persistent changes in their behavior. It has been

suggested that in other cultures, the ration-ale given by patients for losing

weight differs from the fear of fatness characteristic of cases in North

America.

Men have

anorexia nervosa far less frequently than women. However, when the syndrome

does develop in a man, it is typical. There may be an increased frequency of

homosexuality among men with anorexia nervosa.

Related Topics