Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: Eating Disorders

Anorexia Nervosa: Differential Diagnosis

Differential

Diagnosis

Although

depression, schizophrenia and obsessive–compulsive disorder may be associated

with disturbed eating and weight loss, it is rarely difficult to differentiate

these disorders from anorexia nervosa. Individuals with major depression may

lose significant amounts of weight but do not exhibit the relentless drive for

thin-ness characteristic of anorexia nervosa. In schizophrenia, starva-tion may

occur because of delusions about food, for example, that it is poisoned.

Individuals with obsessive–compulsive disorder may describe irrational concerns

about food and develop rituals related to meal preparation and eating but do

not describe the intense fear of gaining weight and the pervasive wish to be

thin that characterize anorexia nervosa.

A wide

variety of medical problems cause serious weight loss in young people and may

at times be confused with anorexia nervosa. Examples of such problems include

gastric outlet ob-struction, Crohn’s disease and brain tumors. Individuals

whose weight loss is due to a general medical illness generally do not show the

drive for thinness, the fear of gaining weight and the increased physical

activity characteristic of anorexia nervosa. However, the psychiatrist is well

advised to consider any chronic medical illness associated with weight loss,

especially when evaluating individuals with unusual clinical presentations such

as late age at onset or prominent physical complaints, for exam-ple, pain and

gastrointestinal cramping while eating.

Course and Natural History

The

course of anorexia nervosa is enormously variable. Some in-dividuals have mild

and brief illnesses and either never come to medical attention or are seen only

briefly by their pediatrician or general medical physician. It is difficult to

estimate the frequency of this phenomenon because such individuals are rarely

studied.

Most of

the literature on course and outcome is based on individuals who have been

hospitalized for anorexia nervosa. Although such individuals presumably have a

relatively severe illness and adverse outcomes, a substantial fraction,

probably between one-third and one-half, make full and complete psy-chological

and physical recoveries. On the other hand, anorexia nervosa is also associated

with an impressive long-term mortal-ity. The best data currently available

suggest that 10 to 20% of patients who have been hospitalized for anorexia nervosa

will, in the next 10 to 30 years, die as a result of their illness. Much of the

mortality is due to severe and chronic starvation, which eventu-ally terminates

in sudden death. In addition, a significant fraction of patients commit

suicide.

Between these

two extremes are a large number of indi-viduals whose lives are impaired by

persistent difficulties with eating. Some are severely affected maintaining a

chronic state of semistarvation, bizarre eating rituals and social isolation;

others may gain weight but struggle with bulimia nervosa and strict rules about

food and eating; and still others may recover initially but then relapse into

another full episode. There is a high fre-quency of depression among

individuals who have had anorexia nervosa and a significant frequency of drug

and alcohol abuse, but psychotic disorders develop only rarely. Thus, in

general, in-dividuals either recover or continue to struggle with

psychologi-cal and behavioral problems that are directly related to the eating

disorder. It is of note that it is rare for individuals who have had anorexia

nervosa to become obese.

It is

difficult to specify factors that account for the vari-ability of outcome in

anorexia nervosa. A significant body of experience suggests that the illness

has a better prognosis whenit begins in adolescence, but there are also

suggestions that pre-pubertal onset may portend a difficult course. It is

likely that the severity of the illness (e.g., the lowest weight reached, the

number of hospitalizations) and the presence of associated symptoms, such as

binge-eating and purging, also contribute to poor out-come. However, it is

impossible to predict course and outcome in an individual with any certainty.

Goals of Treatment

The first

goal of treatment is to engage the patient and her or his family. For most

patients with anorexia nervosa, this is chal-lenging. Patients usually minimize

their symptoms and suggest that the concerns of the family and friends, who

have often been instrumental in arranging the consultation, are greatly

exag-gerated. It is helpful to identify a problem that the patient can

acknowledge, such as weakness, irritability, difficulty concen-trating, or

trouble with binge-eating. The psychiatrist may then attempt to educate the

patient regarding the pervasive physical and psychological effects of

semistarvation and about the need for weight gain if the acknowledged problem

is to be successfully addressed.

A second

goal of treatment is to assess and address acute medical problems, such as fluid

and electrolyte disturbances and cardiac arrhythmias. Depending on the severity

of illness, this may require the involvement of a general medical physician.

The additional but most difficult and time-consuming goals are the restoration

of normal body weight, the normalization of eating and the resolution of the

associated psychological disturbances. The final goal is the prevention of

relapse.

Treatment

A common

major impediment to the treatment of patients with anorexia nervosa is their

disagreement with the goals of treat-ment; many of the features of their

illness are simply not viewed by patients as a problem. In addition, this may

be compounded by a variety of concerns of the patient, such as basic mistrust

of relationships, feelings of vulnerability and inferiority, and sen-sitivity

to perceived coercion. Such concerns may be expressed through considerable

resistance, defiance, or pseudocompliance with the psychiatrist’s interventions

and contribute to the power struggles that often characterize the treatment

process. The psy-chiatrist must try to avoid colluding with the patient’s

attempts to minimize problems but at the same time allow the patient enough

independence to maintain the alliance. Dealing with such dilem-mas is

challenging and requires an active approach on the part of the psychiatrist. In

most instances, it is possible to preserve the alliance while nonetheless

adhering to established limits and the need for change.

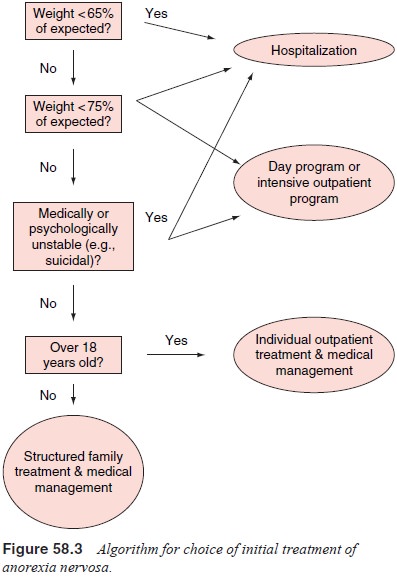

The

initial stage of treatment should be aimed at reversing the nutritional and

behavioral abnormalities (Figure 58.3). The intensity of the treatment required

and the need for partial or full hospitalization should be determined by the

current weight, the rapidity of weight loss, and the severity of associated

medical and behavioral problems and of other symptoms such as depression. In

general, patients whose weights are less than 75% of expected should be viewed

as medically precarious and require intensive treatment such as

hospitalization.

Most

inpatient or day treatment units experienced in the care of patients with

anorexia nervosa use a structured treatment approach that relies heavily on

supervision of calorie intake by the staff. Patients are initially expected to

consume sufficient cal-ories to maintain weight, usually requiring 1500 to 2000

kcal/day

in four

to six meals. After the initial medical assessment has been completed and

weight has stabilized, calorie intake is gradually increased to an amount

necessary to gain 2 to 5 lb/week. Because the consumption of approximately 4000

kcal beyond mainte-nance requirements is needed for each pound of weight gain,

the daily calorie requirements become impressive, often in the range of 4000

kcal/day. Some eating disorder units provide only food while others rely on

nutritional supplements such as Ensure or Sustacal. During this phase of

treatment it is necessary to moni-tor patients carefully; many will resort to

throwing food away or vomiting after meals. Careful supervision is also

required to obtain accurate weights; patients may consume large amounts of

fluid before being weighed or hide heavy articles under their clothing.

During

the weight restoration phase of treatment patients require substantial

emotional support. It is probably best to ad-dress fears of weight gain with

education about the dangers of semistarvation and with the reassurance that

patients will not be allowed to gain “too much” weight. Most eating disorders

units impose behavioral restrictions, such as limits on physical activ-ity,

during the early phase of treatment. Some units use an ex-plicit behavior

modification regimen in which weight gain is tied to increased privileges and

failure to gain weight results in bed rest.

A

consistent and structured treatment approach, with or without an explicit

behavior modification program, is generally successful in promoting weight

recovery but requires substantial energy and coordination to maintain a

supportive and nonpunitivetreatment environment. In most experienced treatment

units, parenteral methods of nutrition, such as nasogastric feeding or

intravenous hyperalimentation, are only rarely needed. Nutri-tional counseling

and behavioral approaches can also be effec-tive in helping patients expand

their dietary repertoire to include foods they have been frightened of

consuming.

As weight

increases, individual, group and family psycho-therapy can begin to address

other issues in addition to the dis-tress engendered by gaining weight. For

example, it is typically important for patients to recognize that they have

come to base much of their self-esteem on dieting and weight control and are

likely to judge themselves according to harsh and unforgiving standards.

Similarly, patients should be helped to see how the eating disorder has interfered

with the achievement of personal goals such as education, sports, or making

friends.

There is,

present, no general agreement about the most useful type of psychotherapy or

the specific topics that need to be addressed. Most eating disorders programs

employ a variety of psychotherapeutic interventions. A number of psychiatrists

recommend the use of individual and group psychotherapy us-ing

cognitive–behavioral techniques to modify the irrational overemphasis on

weight. Although most authorities see little role for traditional

psychoanalytic therapy, individual and group psychodynamic therapy can address

such problems as insecure attachment, separation and individuation, sexual

relationships and other interpersonal concerns. There is good evidence sup-porting

the involvement of the family in the treatment of younger patients with

anorexia nervosa. Family therapy can be helpful in addressing family members’

fears about the illness; interventions typically emphasize parental

cooperation, mutual support and consistency, and establishing boundaries

regarding the patient’s symptoms and other aspects of his or her life.

Despite

the multiple physiological disturbances associ-ated with anorexia nervosa,

there is no clearly established role for medication. The earliest systematic

medication trials in ano-rexia nervosa focused on the use of neuroleptics.

Theoretically, such agents might help to promote weight gain, to reduce

physi-cal activity and to diminish the distorted thinking about shape and

weight, which often reaches nearly delusional proportions. Early work in the

late 1950s and 1960s using chlorpromazine led to substantial enthusiasm, but

two placebo-controlled trials of the neuroleptics, sulpiride and pimozide, were

unable to establish significant benefits. In recent years interest has grown in

taking advantage of the impressive weight gain associated with some atypical

antipsychotics; however, no controlled data supporting this intervention have

yet appeared. Despite the frequency of de-pression among patients with anorexia

nervosa, there is no good evidence supporting the use of antidepressant

medication in their treatment.

Unfortunately,

although controlled trials have provided some evidence of benefit, the impact

of cyproheptadine, an anti-histamine, in anorexia nervosa appears limited.

A large

percentage of patients with anorexia nervosa re-main chronically ill; 30 to 50%

of patients successfully treated in the hospital require rehospitalization

within 1 year of discharge. Therefore, posthospitalization outpatient

treatments are recom-mended to prevent relapse and improve overall short- and

long-term functioning. Several studies have attempted to evaluate the efficacy

of various outpatient treatments for anorexia nervosa including behavioral,

cognitive–behavioral and supportive psy-chotherapy, as well as a variety of

nutritional counseling inter-ventions. Although most of these treatments seem

to be helpful the clearest findings to date support two interventions. For

pa-tients whose anorexia nervosa started before age 18 years and who have had

the disorder for less than 3 years, family therapy is effective, and for adult

patients, cognitive–behavioral therapy reduces the rate of relapse. Preliminary

information suggests that fluoxetine treatment may reduce the risk of relapse

among patients with anorexia nervosa who have gained weight, but ad-ditional

controlled data are required to document the usefulness of this intervention.

Refractory Patients

Some

patients with anorexia nervosa refuse to accept treatment and thereby can raise

difficult ethical issues. If weight is ex-tremely low or if there are acute

medical problems, it may be ap-propriate to consider involuntary commitment.

For patients who are ill but more stable, the psychiatrist must weigh the

short-term utility of involuntary treatment against the disruption of a

poten-tial alliance with the patient.

The goals of treatment may need to be modified for patients with chronic illness who have failed multiple previous attempts at inpatient and outpatient care. Treatment may be appropriately aimed at preventing further medical, psychological and social de-terioration in the hope that the anorexia nervosa may eventually improve with time.

Related Topics