Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: Eating Disorders

Bulimia Nervosa: Differential Diagnosis

Differential

Diagnosis

Bulimia

nervosa is not difficult to recognize if a full history is available. The

binge-eating/purging type of anorexia nervosa has much in common with bulimia

nervosa but is distinguished by the characteristic low body weight and, in

women, amenorrhea. Some individuals with atypical forms of depression overeat

when de-pressed; if the overeating meets the definition of a binge described

previously (i.e., a large amount of food is consumed with a sense of loss of

control) and if the binge-eating is followed by inappro-priate compensatory

behavior, occurs sufficiently frequently and is associated with over concern

regarding body shape and weight, an additional diagnosis of bulimia nervosa may

be warranted. Some individuals become nauseated and vomit when upset; this and

similar problems are probably not closely related to bulimia nervosa and should

be viewed as a somatoform disorder.

Many

individuals who believe they have bulimia nervosa have a symptom pattern that

fails to meet full diagnostic crite-ria because the frequency of their

binge-eating is less than twice a week or because what they view as a binge

does not contain an abnormally large amount of food. Individuals with these

characteristics fall into the broad and heterogeneous category of atypical

eating disorders. Binge-eating disorder, a category currently included in the

DSM-IV appendix B for categories that need additional research, is

characterized by recurrent binge-eating similar to that seen in bulimia nervosa

but without the regular occurrence of inappro-priate compensatory behavior.

Course and Natural History

Over

time, the symptoms of bulimia nervosa tend to improve although a substantial

fraction of individuals continue to engage in binge-eating and purging. On the

other hand, some controlled clinical trials have reported that structured forms

of psychother-apy have the potential to yield substantial and sustained

recovery in a significant fraction of patients who complete treatment. It is

not clear what factors are most predictive of good outcome, but those

individuals who cease binge-eating and purging com-pletely during treatment are

least likely to relapse.

Goals of Treatment

The goals

of the treatment of bulimia nervosa are straightfor-ward. The binge-eating and

inappropriate compensatory behav-iors should cease and self-esteem should

become more appropri-ately based on factors other than shape and weight.

Treatment

The power

struggles that often complicate the treatment proc-ess in anorexia nervosa

occur much less frequently in the treat-ment of patients with bulimia nervosa.

This is largely because the critical behavioral disturbances, binge-eating and

purging, are less egosyntonic and are more distressing to these patients. Most

bulimia nervosa patients who pursue treatment agree with the primary treatment

goals and wish to give up the core behavioral features of their illness.

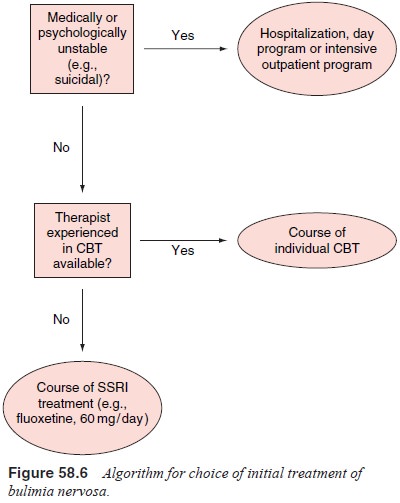

The

treatment of bulimia nervosa has received consider-able attention in recent

years and the efficacies of both psycho-therapy and medication have been

explored in numerous control-led studies (Figure 58.6). The form of

psychotherapy that has been examined most intensively is cognitive–behavioral

therapy, modeled on the therapy of the same type for depression.

Cogni-tive–behavioral therapy for bulimia nervosa concentrates on the distorted

ideas about weight and shape, on the rigid rules regard-ing food consumption

and the pressure to diet and on the events that trigger episodes of

binge-eating. The therapy is focused and highly structured and is usually

conducted in 3 to 6 months. Ap-proximately 25 to 50% of patients with bulimia

nervosa achieve abstinence from binge-eating and purging during a course of

cog-nitive–behavioral therapy and in most, this improvement appears to be

sustained. The most common form of cognitive–behavioral therapy is individual

treatment, although it can be given in either individual or group format. The

effect of cognitive–behavioral therapy is greater than that of supportive

psychotherapy and of interpersonal therapy, indicating that

cognitive–behavioral therapy should be the treatment of choice for bulimia

nervosa.

The other

commonly used mode of treatment that has been examined in bulimia nervosa is

the use of antidepressant medica-tion. This intervention was initially prompted

by the high rates of depression among patients with bulimia nervosa and has now

been tested in more than a dozen double-blind, placebo-control-led studies

using a wide variety of antidepressant medications. Active medication has been

consistently found to be superior to placebo, and although there have been no

large “head-to-head” comparisons between different antidepressants, most

antide-pressants appear to possess roughly similar antibulimic potency.

Fluoxetine at a dose of 60 mg/day is favored by many investiga-tors because it

has been studied in several large trials and ap-pears to be at least as

effective as, and better tolerated than, mostother alternatives. It is notable

that it has not been possible to link the effectiveness of antidepressant

treatment for bulimia nervosa to the pretreatment level of depression.

Depressed and nonde-pressed patients with bulimia nervosa respond equally well

in terms of their eating behavior to antidepressant medication.

Although

antidepressant medication is clearly superior to placebo in the treatment of

bulimia nervosa, several studies sug-gest that a course of a single

antidepressant medication is gener-ally inferior to a course of

cognitive–behavioral therapy. How-ever, patients who fail to respond adequately

to, or who relapse following a trial of psychotherapy, may still respond to

antide-pressant medication.

Special Features Influencing Treatment

A major

factor influencing the treatment of bulimia nervosa is the presence of other

significant psychiatric or medical illness. For example, it can be difficult

for individuals who are currently abusing drugs or alcohol to use the treatment

methods described, and many psychiatrists suggest that the substance abuse

needs to be addressed before the eating disorder can be effectively treated.

Other examples include the treatment of individuals with bulimia nervosa and

serious personality disturbance and those with insu-lin-dependent diabetes

mellitus who “purge” by omitting insulin doses. In treating such individuals,

the psychiatrist must decide which of the multiple problems must be first

addressed and may elect to tolerate a significant level of eating disorder to

confront more pressing disturbances

Refractory Patients

Although

psychotherapy and antidepressant medication are effective interventions for

many patients with bulimia nervosa, some individuals have little or no

response. There is no clearly es-tablished algorithm for the treatment of such

refractory patients. Alternative interventions that may prove useful include

other forms of psychotherapy and other medications such as opiate an-tagonists

and the serotonin agonist fenfluramine. Hospitalization should also be

considered as a way to normalize eating behavior, at least temporarily, and

perhaps to initiate a more effective out-patient treatment

Related Topics