Chapter: Essential Clinical Immunology: Basic Components of the Immune System

Basic Components of the Immune System

Basic Components of the Immune

System

INTRODUCTION

It is generally believed that the immune system

evolved as the host’s defense against infectious agents, and it is well known

that patients with deficiencies in the immune system generally succumb to these

infectious diseases. However, as we shall see, it may well play a larger role

in the elimina-tion of other foreign substances, including tumor antigens or

cells and antibodies that attack self.

An immune response may be conve-niently divided into

two parts: (1) a specific response to a given antigen and (2) a more

nonspecific augmentation to that response. An important feature of the specific

response is that there is a quicker response to the antigen during a second

exposure to that antigen. It is the memory of the initial response that

provides the booster effect.

For convenience, the specific immune response may

be divided into two parts:

(1) the humoral response and (2) the cellu-lar

response to a given antigen. As we shall see, however, both responses are

medi-ated through the lymphocyte. Humoral responses are antibodies produced in response

to a given antigen, and these anti-bodies are proteins, have similar

structures, and can be divided into various classes of immunoglobulins.

Cellular responses are established by cells and can only be trans-ferred by

cells. (See the Bibliography for the extraordinary beginnings of the con-cept

of a cellular arm of the immune sys-tem.) Up to the 1940s the general dogma

held that only antibodies were involved in the immune response. Dr. Merrill

Chase, who began his experiments in a labora-tory devoted primarily to the

humoral response, clearly showed in a series of ele-gant experiments that

immunity was not just humoral but that a cellular response by the lymphocytes

could also produce immunity. Some of the best examples of the power of cellular

immunity may be found in the many experiments in which transfer of cells can

induce autoimmune disease in animals and humans as well as rejection of an

organ graft in both animals and humans by cells.

The separation of human and cellular immunity was

further advanced by the study of immunodeficient humans and animals. For

example, thymectomized or congenitally athymic animals as well as humans cannot

carry out graft rejection, yet they are capable of producing some antibody

responses. The reverse is also true. Children (and animals) who have an immune

deficit in the humoral response do not make antibodies but can reject

grafts and appear to handle viral, fungal, and some

bacterial infections quite well. An extraordinary finding by Good and

colleagues in studying the cloacal lym-phoid organ in chickens revealed that,

with removal of the bursa Fabricius, these animals lost their ability to

produce anti-bodies and yet retained the ability to reject grafts.

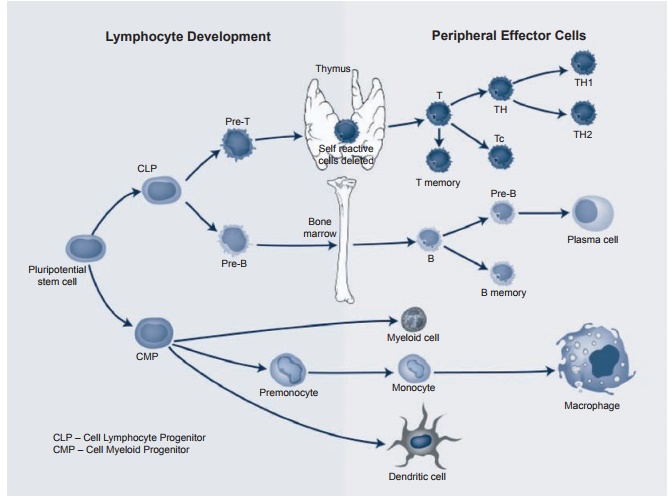

Out of these and many other contribu-tions, a

clearer picture of the division of efforts by lymphocytes begins to emerge.

Since cellular immune responses require an intact thymus, cellular immune

responses are mediated through the T lymphocytes (thymus), while

antibody-producing cells, which are dependent on the bone mar-row (the bursa

equivalent), are known as B (bursa) cells. The pathways of both cell types are

depicted in Figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1 Development

and differentiation of lymphocytes from pluripotential stem cells.

Several types of molecules play a vital role in the

immune response, and we will deal with each in detail. Antigens, both foreign

and self, are substances that may or may not provoke an immune response. Both T

cells and B cells have receptors that recognize these antigens. In the case of

B cells, antibodies on the surface are a major source (but not the only one) of

antigen recognition, and once activated, they differen-tiate into plasma cells

that produce large quantities of antibodies that are secreted into blood and

body fluids to block the harmful effects of the antigen.

T cells have similar receptors known as T-cell

receptors (TCR), and in the con-text of the major histocompatibility complex

(MHC) molecules provide a means of self-recognition and T-lymphocyte effector

functions. Often these effector functions are carried out by messages

transmitted between these cells. These soluble messen-gers are called interleukins or cytokines.

Related Topics