Chapter: The Diversity of Fishes: Biology, Evolution, and Ecology: Fishes as prey

Balancing foraging against predatory threat - Fishes as prey

Balancing foraging against predatory threat

It is important to realize that most predators are also prey and that foraging decisions often must be made in the context of danger to the feeder. These conflicting demands create a foraging–predation risk trade-off. What evidence exists to suggest that foraging fishes take into account risk to their own survival when choosing among food types, locales, and methods? Sticklebacks feed more slowly and gobies eat less in the presence of predators, even when the predators are behind a transparent partition (Magnhagen 1988; Milinski 1993). Juvenile Coho Salmon are less willing to travel long distances to intercept floating prey when presented with photographs of large predatory trout (Dill & Fraser 1984). Juvenile Black Surfperch (Embiotocidae) shift from feeding in low-growing, exposed algae when predatory kelp bass (Serranidae) are absent to feeding in tall, bushy algae when predators are present (Holbrook & Schmitt 1988a). Herbivorous minnows and loricariid

catfishes abandon shallow areas of high algal productivity for deeper, less productive areas to avoid both predatory birds and fishes (Power 1987). Juvenile Bluegill grow fastest when feeding in open water on zooplankton. When Largemouth Bass are released in the open water areas, smaller, more vulnerable Bluegill move into vegetated areas where they have lower mortality rates from predation but also grow more slowly because of lower food intake. Bluegill too large to be swallowed by the bass remain in the open water areas (Werner et al. 1983). Similar trade-offs and attendant costs have been shown in such fishes as Ocean Pout and Guppies (e.g., Botham et al. 2006; Killen & Brown 2006).

The balance between foraging and predation risk is shown by studies that vary the degree of threat and the strength of the reward. Minnows and surfperch will risk feeding in patches where predators are present if food densities are high; otherwise they avoid patches with predators (Gilliam & Fraser 1987; Holbrook & Schmitt 1988b). Additional factors can affect the decision process. Hunger or parasite loads cause sticklebacks to resume feeding sooner after exposure to predators and also cause fishes to feed closer to potential predators (Godin & Sproul 1988; Milinski 1993). When offered food in the presence of a cichlid predator, female Guppies will accept more risk for more reward whereas male Guppies avoid the predator regardless of food availability, implying that reproductive output is more dependent on food intake in females than in males.

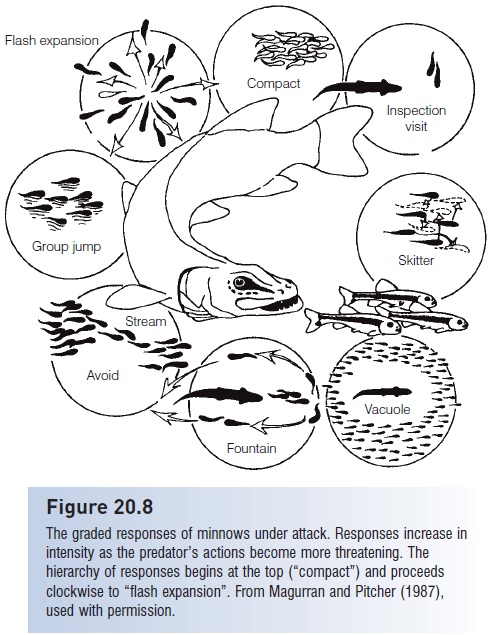

Finally, prey fish do not feed or avoid predators in an all-or-nothing fashion. They appear to weigh the potential threat from a predator and to take action appropriate to the degree of threat. This threat sensitivity is evident in individuals and groups. Territorial damselfishes respond more strongly to larger than to smaller predators and to predators in a strike pose than to searching predators. The strength of the flight behavior elicited also increases as the predator draws closer (Helfman 1989). Minnows in shoals also employ a graded series of escape responses that increase in strength and effectiveness as a pike escalates its attack (see Fig. 20.8), and sticklebacks spend progressively less time foraging as predatory trout increase in number (Fraser & Huntingford 1986; Magurran & Pitcher 1987). Threat sensitivity – to chemical and visual cues and sometimes involving learning by observing avoidance behavior in conspecifics – has also been shown in rainbowfish, sticklebacks, sculpins, and cichlids (Bishop 1992; Brown &Warburton 1997; Chivers et al. 2001; Brown et al. 2006).Threat sensitivity makes good Darwinian sense. A prey individual that is capable of assessing just how threatening a predator is and that is able to devote an appropriate amount of time and energy avoiding the predator will have more time for other fitness-infl uencing activities (feeding, breeding, defending a territory or young) than will an individual that flees or hides any time a predator arrives in the area.

Related Topics