Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Assessment of Renal and Urinary Tract Function

Assessment of Renal and Urinary Tract Function

Assessment

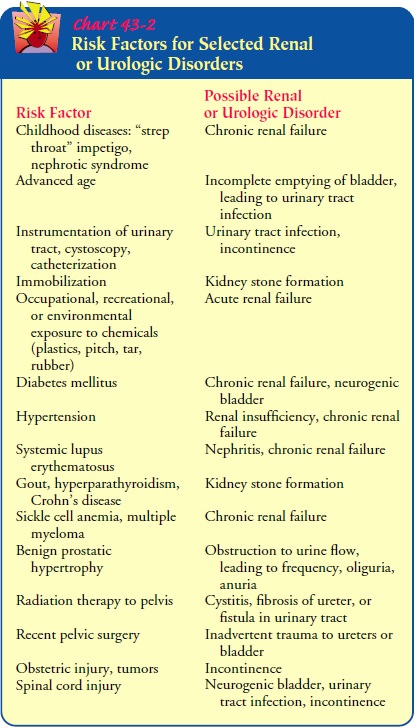

Obtaining

a comprehensive health history, which includes an assessment of risk factors,

is the first step in assessing a patient with upper or lower urinary tract

dysfunction. Various diseases or clinical situations can place a patient at

increased risk for urinary tract dysfunction. Data collection about previous

health problems or diseases provides the health care team with useful

information for evaluating the patient’s current urinary status. Risk factors

for specific disorders and kidney and lower urinary tract dysfunction are

discussed in Chart 43-2.

HEALTH HISTORY

Obtaining a urologic health history requires excellent communication skills because many patients are embarrassed or uncomfortable discussing genitourinary function or symptoms. It is important to use language the patient can understand and to avoid medical jargon. It is also important to review risk factors, particularly with those at risk. For example, the nurse needs to be aware that multiparous women delivering their children vaginally are at high risk for stress urinary incontinence, which if severe enough can also lead to urge incontinence. Elderly women and persons with neurologic disorders such as diabetic neuropathy, multiple sclerosis, or Parkinson’s disease often have incomplete emptying of the bladder with urinary stasis, which may result in urinary tract infection or increasing bladder pressure leading to overflow incontinence, hydronephrosis, pyelonephritis, or renal insufficiency.

Persons

with a family history of urinary tract problems are at increased risk for renal

disorders. Persons with diabetes who have consistent hypertension are at risk

for renal dysfunction (Bakris, Williams, Dworkin et al., 2000). Older men are

at risk for pros-tatic enlargement, which causes urethral obstruction and which

can result in urinary tract infections and renal failure (Degler, 2000).

Moreover, many persons with a history of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE)

develop lupus nephritis (Smith, Fortune-Faulkner & Spurbeck, 2000). When

obtaining the health history, the nurse should inquire about the following:

·

The patient’s chief concern or reason for seeking

health care, the onset of the problem, and its effect on the patient’s quality

of life

·

The location, character, and duration of pain, if

present, and its relationship to voiding; factors that precipitate pain, and

those that relieve it

·

History of urinary tract infections, including past

treatment or hospitalization for urinary tract infection

·

Fever or chills

·

Previous renal or urinary diagnostic tests or use

of indwelling urinary catheters

· Dysuria and when it occurs during voiding (at

initiation ortermination of voiding)

· Hesitancy, straining, or

pain during or after urination

· Urinary incontinence

(stress incontinence, urge inconti-nence, overflow incontinence, or functional

incontinence)

· Hematuria or change in

color or volume of urine

· Nocturia and its date of onset

· Renal calculi (kidney

stones), passage of stones or gravel in urine

· Female patients: number

and type (vaginal or cesarean) of deliveries; use of forceps; vaginal

infection, discharge, or irritation; contraceptive practices

·

Presence or history of genital lesions or sexually

transmitted diseases

· Habits: use of tobacco,

alcohol, or recreational drugs

· Any prescription and

over-the-counter medications (includ-ing those prescribed for renal or urinary

problems)

Gerontologic Considerations

A

thorough medication history is especially important for elderly patients, for

whom the increased occurrence of chronic illness often necessitates

polypharmacy (concurrent use of multiple med-ications). Aging affects the way

the body absorbs, metabolizes,and excretes drugs, thus placing the elderly

patient at risk for ad-verse reactions, including compromised renal function.

Other

key information to obtain while gathering the health history includes an

assessment of the patient’s psychosocial sta-tus, level of anxiety, perceived

threats to body image, available support systems, and sociocultural patterns.

Obtaining this in-formation during the initial and subsequent nursing

assessments enables the nurse to uncover special needs, misunderstandings, lack

of knowledge, and need for patient teaching. Pain, changes in voiding, and

gastrointestinal symptoms are particularly sug-gestive of urinary tract

disease. Dysfunction of the kidney can produce a complex array of symptoms

throughout the body.

Unexplained Anemia

Gradual kidney dysfunction can be insidious in its presentation, al-though fatigue is a common symptom. Fatigue, shortness of breath, and exercise intolerance all result from the condition known as “anemia of chronic disease.” Although hematocrit has been the blood test of choice when assessing a patient for anemia, the 2001 Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative: Management of Ane-mia Guidelines recommend that anemia be quantified using he-moglobin level rather than hematocrit, because that measurement is a better assessment of circulating oxygen (Eschbach, 2001).

Pain

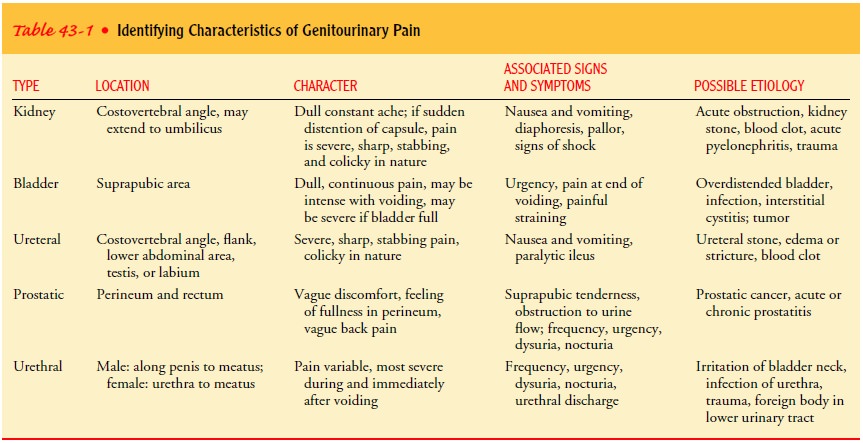

Genitourinary

pain is usually caused by distention of some por-tion of the urinary tract

because of obstructed urine flow or in-flammation and swelling of tissues.

Severity of pain is related to the sudden onset rather than the extent of

distention.

Table

43-1 lists the various types of genitourinary pain, char-acteristics of the

pain, associated signs and symptoms, and possi-ble causes. However, kidney

disease does not always involve pain. It tends to be diagnosed because of other

symptoms that cause a patient to seek health care, such as pedal edema,

shortness of breath, and changes in urine elimination (Kuebler, 2001).

Changes in Voiding

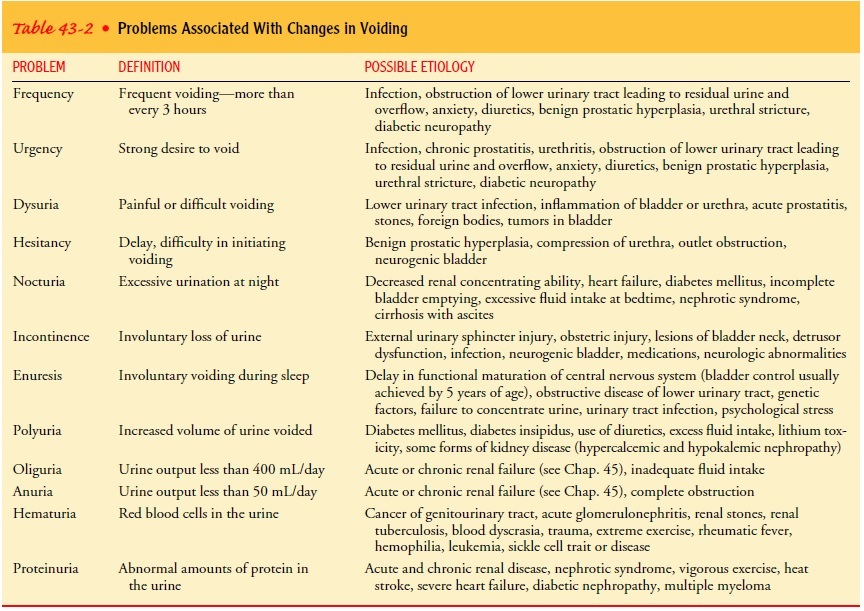

Voiding

(micturition) is normally a painless function occurring ap-proximately eight

times in a 24-hour period. The average person voids 1,200 to 1,500 mL of urine

in 24 hours, although this amount varies depending on fluid intake, sweating,

environmental temper-ature, vomiting, or diarrhea. Common problems associated

with voiding include frequency,

urgency, dysuria, hesitancy, inconti-nence, enuresis, polyuria, oliguria, and hematuria. These problems

and others are described in Table 43-2. Increased urinary urgency and frequency

coupled with decreasing urine volumes strongly sug-gest urine retention.

Depending on the acuity of the onset of these symptoms, immediate bladder

emptying via catheterization and evaluation are necessary to prevent kidney

dysfunction (Gray, 2000a).

Gastrointestinal Symptoms

Gastrointestinal

symptoms may occur with urologic conditions because of shared autonomic and

sensory innervation and reno-intestinal reflexes. The anatomic relation of the

right kidney to the colon, duodenum, head of the pancreas, common bile duct,

liver, and gallbladder may cause gastrointestinal disturbances. The prox-imity

of the left kidney to the colon (splenic flexure), stomach,pancreas, and spleen

may also result in intestinal symptoms. The most common signs and symptoms

include nausea, vomiting, di-arrhea, abdominal discomfort, and abdominal

distention. Uro-logic symptoms can mimic such disorders as appendicitis, peptic

ulcer disease, or cholecystitis, thus making diagnosis difficult, es-pecially

in the elderly, because of decreased neurologic innerva-tion to this area

(Kuebler, 2001; Wade-Elliot, 1999).

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

Several

body systems can affect upper and lower urinary tract dys-function, and that

dysfunction can affect several end organs; therefore, a head-to-toe assessment

is indicated. Areas of empha-sis include the abdomen, suprapubic region,

genitalia and lower back, and lower extremities.

Direct

palpation of the kidneys may help determine their size and mobility. The

correct position for palpation is presented in Figure 43-5. It may be possible

to feel the smooth, rounded lower pole of the kidney between the hands,

although the right kidney is easier to feel because it is somewhat lower than

the left one. In obese patients, palpation of the kidneys is generally more

difficult.

Renal

dysfunction may produce tenderness over the costover-tebral angle, which is the

angle formed by the lower border of the 12th, or bottom, rib and the spine. The

abdomen (just slightly to the right and left of midline in both upper

quadrants) is auscul-tated to assess for bruits (low-pitched murmurs that

indicate renal artery stenosis or an aortic aneurysm). The abdomen is also

as-sessed for the presence of peritoneal fluid, which may occur with kidney

dysfunction.

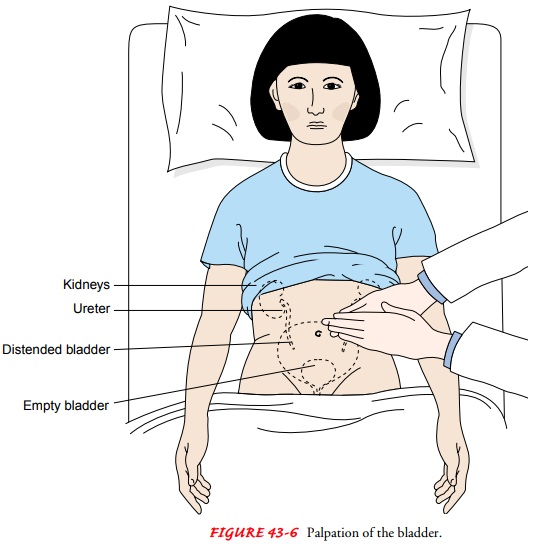

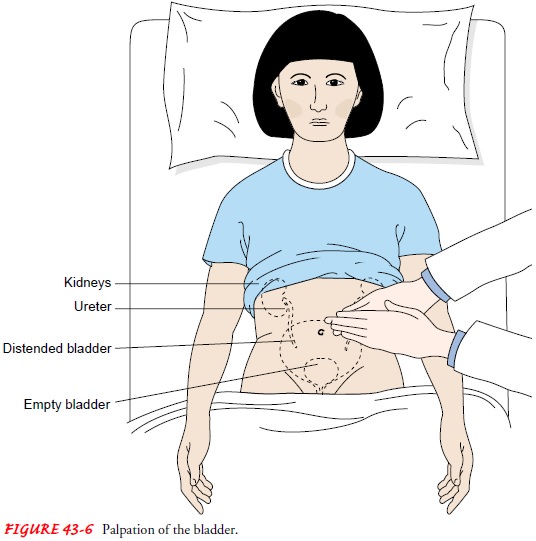

The

bladder should be percussed after the patient voids to check for residual

urine. Percussion of the bladder begins at the midline just above the umbilicus

and proceeds downward. The sound changes from tympanic to dull when percussing

over the bladder. The bladder, which can be palpated only if it is moderately

dis-tended, feels like a smooth, firm, round mass rising out of the ab-domen,

usually at midline (Fig. 43-6). Dullness to percussion of the bladder following

voiding indicates incomplete bladder emptying.

In

older men, benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) is a common cause of urinary

dysfunction. Because the signs and symptoms of prostate cancer can mimic those

of BPH, the prostate gland is pal-pated by digital rectal examination (DRE) as

part of the yearly physical examination in men ages 50 and older (45 if there

is a family history of prostate cancer). In addition, a blood specimen is

obtained to test the prostate specific antigen (PSA) level annu-ally; the

results of the DRE and PSA are then correlated. Blood is drawn for PSA before

the DRE because manipulation of the prostate can cause the PSA level to rise

temporarily. The inguinal area is examined for enlarged nodes, an inguinal or

femoral her-nia, or varicocele (varicose veins of the spermatic cord) (American

Foundation for Urological Disease, 2000; Degler, 2001).

In

women, the vulva, urethral meatus, and vagina are exam-ined. The urethra is

palpated for diverticula and the vagina is assessed for adequate estrogen effect

and any of five types of her-niation (Goolsby, 2001). Urethrocele is the

bulging of the ante-rior vaginal wall into the urethra. Cystocele is the

herniation of the bladder wall into the vaginal vault. The cervix bulging into

the vaginal vault is referred to as pelvic prolapse. Enterocele is her-niation

of the bowel into the posterior vaginal wall, and rectocele is the herniation

of the rectum into the vaginal wall. These pro-lapses are graded depending on

the degree of herniation.

The

woman is asked to cough and perform a Valsalva maneu-ver to assess the

urethra’s system of muscular and ligament sup-port. If urine leakage occurs,

the index and middle fingers of the examiner’s gloved hand are used to support

either side of the urethra as the woman is asked to repeat these maneuvers.

This is called the Marshall-Boney maneuver.

If no

urine leakage is detected when external support is pro-vided to the urethra,

poor pelvic floor support—referred to as urethral hypermobility—is identified

as the suspected cause of the urinary incontinence. Stress urinary incontinence

(SUI) is graded based on its severity. Grade 1 and Grade 2 SUI relate to the

degree of urethral hypermobility. Grade 3, the most severe form of SUI, refers

to the inability of the urethral walls to remain compressed with abdominal

pressure such as a cough or Valsalva maneuver. Grade 3 is referred to as

intrinsic sphincter deficiency (ISD) (Albaugh, 1999).

If

some residual leakage of urine is noted despite support, ISD is suspected.

Urethral hypermobility may be suspected when Q-tip test results are positive.

The Q-tip test involves gently placing a well-lubricated Q-tip into the urethra

until resistance is no longer noted, then gently pulling back on the Q-tip

until resistance is felt. The female patient is asked to cough and perform the

Val-salva maneuver. If there is an upward (positive deflection) of the visible

part of the Q-tip, urethral hypermobility is at least one of the causes for the

type of incontinence referred to as stress in-continence.

The patient is assessed for edema and changes in body weight. Edema may be observed, particularly in the face and dependent parts of the body, such as the ankles and sacral areas, and suggests fluid retention. An increase in body weight commonly accompa-nies edema. A 1-kg weight gain equals approximately 1,000 mL of fluid.

The

deep tendon reflexes of the knee are assessed for quality and symmetry. This is

an important part of testing for neurolog-ical causes of bladder dysfunction

because the sacral area, which innervates the lower extremities, is the same

peripheral nerve area responsible for urinary continence. The gait pattern of

the indi-vidual with bladder dysfunction is also noted, as well as the

pa-tient’s ability to walk toe-to-heel. These tests evaluate possible

supraspinal causes for urinary incontinence (Appell, 1999).

Gerontologic Considerations

Upper and lower urinary tract function

changes with age. The GFR decreases with age starting between ages 35 and 40. A

yearly decline of about 1 mL/min continues thereafter. Tubular function,

in-cluding reabsorption and concentrating ability, is also reduced with

increasing age. Although renal function usually remains adequate despite these

changes, renal reserve is decreased and may reduce the kidneys’ ability to

respond effectively to drastic or sudden physio-logic changes. This steady

decrease in glomerular filtration, com-bined with the use of multiple

medications whose metabolites clear the body via the kidneys, puts the older

individual at higher risk for adverse drug effects and drug-to-drug

interactions (Schafer, 2001).

Structural

or functional abnormalities that occur with aging may prevent complete emptying

of the bladder. This may be dueto decreased bladder wall contractility, due to

myogenic or neu-rogenic causes, or structurally, related to bladder outlet

obstruc-tion, as in BPH. Vaginal and urethral tissues atrophy (become thinner)

in aging women due to decreased estrogen levels. This causes decreased blood supply

to the urogenital tissues, causing urethral and vaginal irritation and urinary

incontinence.

Urinary

incontinence is the most common reason for admis-sion to skilled nursing

facilities. Many older individuals and their families are unaware that urinary

incontinence stems from many causes. The nurse needs to inform the patient and

family that with appropriate evaluation, urinary incontinence can often be

managed at home and in many cases can be eliminated (Degler, 2000). Many

treatments are available for urinary incontinence in the elderly, including

noninvasive, behavioral interventions that the individual or the caregiver can

carry out (Kincade, Peckous Busby-Whitehead, 2001).

Preparation

of the elderly patient for diagnostic tests must be managed carefully to

prevent dehydration, which might precipi-tate renal failure in a patient with

marginal renal reserve. Limita-tions in mobility may affect an elderly

patient’s ability to void adequately or to consume an adequate volume of

fluids. The pa-tient may limit fluid intake to minimize the frequency of

voiding or the risk of incontinence. Teaching the patient and family about the

dangers of an inadequate fluid intake is an important role of the nurse caring

for the elderly patient.

Related Topics