Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: Hypnosis

Applications of Hypnosis

Applications

of Hypnosis

General Considerations

Because

of the intrinsic qualities of the hypnotic state, it can be an effective

adjunct to the treatment of a variety of symptoms and problems, both in

psychiatry and in medicine in general. The first criterion to consider is the

patient’s level of hypnotizability. Once it has been determined that the

patient has usable hypnotic capacity (defined by high scores in hypnotizability

scales), a dis-cussion about the nature of the hypnotic process follows. It is

important at this point to dispel any myths and correct miscon-ceptions the

patient may have about the process. This includes the cooperative nature of the

hypnotic process, rather than the “tell me what to do” most patients expect.

Finally, the therapist must decide whether the problem presented by the patient

is ame-nable to hypnotic intervention or whether other steps should be taken

instead.

We have

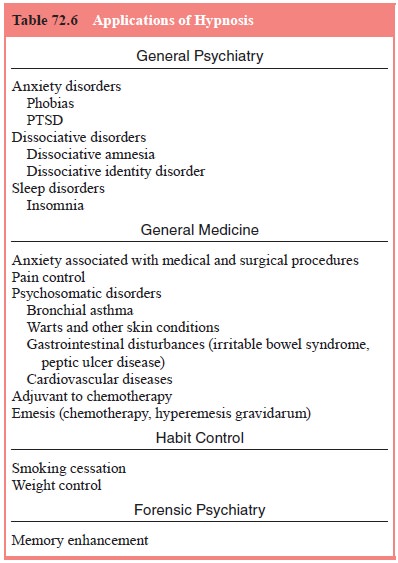

divided the discussion of the applications of hypnosis into five areas: general

psychiatry, general medicine, psychosomatic disorders, habit control and

forensic psychiatry (Table 72.6).

Application in Psychiatric Disorders

The use

of hypnosis in the context of conventional psycho-therapy can facilitate the therapeutic

process in a number of ways. For example, hypnotherapeutic techniques may be

used to enhance the patient’s sense of self, restructure traumatic and phobic

experiences, or access to repressed memories that havenot emerged with use of

other techniques. This is true not only of painfully repressed memories but

also of situations in which both the patient and the therapist have worked on

resistance issues and feel that some additional leverage is necessary. In

conventional psychotherapy, the transference is observed and analyzed; in

hypnosis, the transference is used as part of the therapeutic process.

Conventional

psychoanalytic psychotherapy involves observation and analysis of the meaning

of the transference reaction that arises during therapeutic interactions. On

the other hand, when hypnosis is used, transference is not avoided or bypassed

but may be amplified. All the usual therapeutic rules and processes of

psychotherapy apply when hypnosis is used in the psychotherapy context, which

may intensify or accelerate the therapeutic process.

Because

of the intense emotions that are characteristic of the hypnotic retrieval

(which facilitates expression of inner fantasies), intense feelings and deep

personal experiences may be elicited. Some patients may find that the hypnotic

state facilitates a sense of infantile dependency in which the therapist

becomes the transferential object. The quality of this transference reaction

will be based on the patient’s early object relations, just as in any other therapeutic

relationship. Indeed, the transference reaction may develop so fast that the

inexperienced therapist may not have the opportunity to recognize it or may do

so too late. The difference here is the intensity of the feelings developed as

a result of the strong emotions that arise during trance. As in the case of

victims of abuse, the therapist may use the transference relationship under

hypnosis to foster the patient’s ability to help herself or himself.

The

difficult aspect of doing hypnosis is not the induction of the hypnosis trance,

but what happens once the patient is under trance. Remember that all hypnosis

is self-hypnosis. Thus, there are two factors which will predict the success of

the hypnosis in-tervention: the patients’ hypnotizability and the therapeutic

skills of the therapist.

Anxiety Disorders

Anxiety

disorders are among the most widely prevalent psy-chiatric disturbances. They

afflict as much as 15% of the pop-ulation (Myers et al., 1984). Anxiety can be seen as a state of hyperarousal

experienced by both emotional and somatic discomfort. Patients describe their

experience in physical terms, such as palpitations, gastrointestinal

discomfort, chest pain, sweating and motor restlessness. Among anxiety

disor-ders most responsive to hypnotic intervention are generalized anxiety

disorder, panic disorder, phobias and post traumatic anxiety disorders.

Most of

the strategies in the treatment of anxiety disor-ders employing hypnosis

combine instructed physical relaxation with a restructuring of cognition, using

imagery coupled with physical relaxation. As in the treatment of anxiety

disorders by systematic desensitization (Marks et al., 1968) or progressive relaxation, patients are instructed to

maintain a physical sense of relaxation (e.g., floating) while picturing the

feared situation or stimulus. It is important that the relaxation instruction

use an image that connotes reduced somatic tension, such as floating or

lightness, rather than being a direct instruction to relax. The more cognitive

term “relax” may actually induce more anxiety, whereas affiliation with a

somatic metaphor usually produces some reduction in tension. Unlike systematic

desensitization, hypnosis produces a physically relaxed state that can be

rapidly achieved with a quick induction. Also different from systematic

desensitization, the coupling of relaxation to a fearful stimu-lus does not

require the development or working through of a hierarchy.

A typical

self-hypnosis induction can be rapid. For exam-ple, a patient can be told:

Now just

get as comfortable as you can. There are many ways to enter a state of

self-hypnosis. One simple but useful method is to count to yourself from 1 to

3. On 1, do one thing: look up. On 2, do two things: slowly close your eyes and

take a deep breath. On 3, do three things: let your eyes relax but keep them

closed, let your breath out, and let your body float. Then let one hand or the

other float up into the air like a buoyant balloon. This is your signal to

yourself and to me that you are ready to concentrate.

Initially,

the use of hypnosis in the session can help in demon-strating to patients that

they have a greater degree of control over somatic responsiveness than they had

imagined. It is often useful to begin by teaching patients to create a place in

their mind’s eye where they feel safe and secure. On occasion, it helps the

subjects to learn how to project their image onto an imaginary screen. Later,

they can learn to manipulate the screen by making it either bigger or smaller,

having the screen nearer or farther away, as needed:

Just

allow your body to float, as if you were floating in a bath, a lake, or a hot

tub. Enjoy this sense of floating lightness. Now, picture in your mind’s eye an

imaginary screen. It might be a movie screen, a television screen, or a piece

of clear blue sky. First picture a pleasant scene, somewhere you enjoy being.

Allow the

patient to experience this state for a minute or two, then inquire about the

experience:

With your

eyes closed and remaining in this state of concentra-tion, describe how your

body is feeling right now. What image are you picturing?

After

receiving the answers, add:

Notice

how you can use your store of memories and fantasies to help yourself and your

body feel better.

After

they have learned to manipulate the screen and their physical sensations,

patients may be ready to do therapy work. They may, for example, learn to

re-create the physical state of relaxation while projecting the fearful

situation onto the screen. This, then, becomes a useful procedure by which to

control and obtain mastery over anxiety-producing situations by dissoci-ating

the somatic reaction from the psychological response to the feared stimulus.

Initially, the patient is asked to re-create the physical feeling of

relaxation. Then, the patient projects onto the screen images associated with

the feared situation, only this time the somatic reactions associated with

anxiety do not develop. On occasion, it helps for patients to foresee likely

physical sensations or situations associated with a fearful expe-rience to

master them. For example, in the case of plane phobia, the patient can learn to

couple the real sensation of floating in the air with the hypnotic experience:

“Learn to float with the plane”.

Patients

may also use the trance state as a means of facing their concerns more

directly. As in the preceding cases, they may make use of the screen technique.

They can achieve this by plac-ing an image of an upcoming performance or

fearful situation on one side of the screen, testing out various strategies for

mastering the situation on the other side.

Other

approaches using hypnosis have included instructing patients in a trance to

imagine that they are literally somewhere else, away from the fearful stimulus,

thus separating themselves from the anxiety-producing experience (Erickson and

Haley, 1967). Positive reinforcement or “ego-strengthening” techniques have

also been used; for example, hypnotic instructions are given to patients

suggesting that their capacity to master the situation and their response to it

will improve (Crasilneck and Hall, 1985). There is little reason to use

uncovering techniques seeking to link anxiety to some early traumatic

experience in cases of phobia or generalized anxiety disorders. This is

different in cases of PTSD (DSM-IV-TR), however, in which more work may be

needed to confront and place into context the traumatic experience.

Certainly,

in some cases, understanding the cause of the feared situation may help resolve

the conflict. One of the tech-niques used to facilitate the recovery of

traumatic memories associated with fearful situations is the affect bridge

technique (Watkins, 1987).

Post Traumatic Stress Disorder

Trauma constitutes

a sudden discontinuity in both physical and mental experiences. The effect of

the traumatic experience forces the victim to reorganize mental and

psychophysiological proc-esses to buffer the immediate impact of the trauma.

This process is meant to be an adaptive mechanism to maintain psychologi-cal

control during a time of enormous stress. Unfortunately, a number of trauma

victims go on to suffer acute or chronic symp-toms, such as dissociation,

intrusive thoughts, anxiety, with-drawal and hyperarousal, leading to a

diagnosis of acute stress disorder or PTSD.

There may

be a relationship during childhood between stress, such as early trauma, and

high hypnotizability. In support of this idea are reports of high

hypnotizability in children who were victims of severe punishment during

childhood (Nash and Lynn, 1986; Spiegel and Cardeña, 1991). It is possible that

the impact of the stress suffered encouraged them to use their self-hypnotic

abilities more effectively (Kluft, 1984, 1992; Spiegel et al., 1982).

The major

categories of symptoms in PTSD are similar to the components of the hypnotic

process (American Psychiatric Association, 1994; Maldonado and Spiegel, 2002a).

Hypnotic absorption is similar to the intrusive reliving of traumatic events

experienced by these patients. When in a flashback, trauma victims become so

absorbed in the memories of the traumatic event, they lose touch with their

present surroundings and even forget that the events took place in the past.

Likewise, highly hypnotizable individuals may become so intensely absorbed in

the trance experience that they can reenact a previous life event (during

hypnotic age regression) as if they were reliving it. A hypnotized patient may

dissociate a body part to the extent of not recognizing it as part of his or

her body. Similarly, PTSD patients may dissociate feelings to the extent of

experiencing the so-called psychic numbing. This allows them to disconnect

current affects from their everyday experience in an attempt to avoid emotions

triggering memories associated with the trauma. Finally, suggestibility is

comparable to hyperarousal. The heightened sensitivity to environmental cues

observed in those patients suffering from PTSD is similar to that experienced

by a hypnotized individual who responds to suggestions of coldness by

shivering.

Because

many patients suffering from PTSD are highly hypnotizable, and because of the

resemblance between the symp-toms of PTSD and the hypnotic phenomena, it makes

sense to use hypnosis in its treatment. If patients suffering from PTSD are

unknowingly using their own hypnotic capacities (Kluft, 1991, 1992; Maldonado

and Spiegel, 2002a; Spiegel 1986, 1989; Spiegel et al., 1988), it is therapeutically useful to teach them how to

enter, access and control their trance potential. Hypnosis may be invaluable as

a tool to access previously dissociated traumatic material.

We do not

refer here to uncontrolled abreaction. The purpose is not simply to help the

patient remember the trauma, because in a way, every time a patient goes

through a flashback, an uncontrolled abreaction is experienced. An abreaction

that is not conducted within the context of cognitive restructuring and before

new defenses are in place can lead to the further retraumatization of the patient

(Kluft, 1992; Spiegel, 1981). At the end of the following section (Dissociative

Disorders), we summarize a comprehensive approach to the use of hypnosis in the

treatment of psychiatric syndromes associated with severe trauma.

Dissociative Disorders

Hypnosis

is one of the most helpful tools in the treatment of patients suffering from

dissociative disorders (Maldonado and Spiegel, 2002a; Maldonado et al., 2000). As a rule, these patients

experience their symptoms (i.e., fugue states, dissociated identities and

blackouts) as occurring unexpectedly and beyond their control. Because these

patients are unknowingly using their hypnotic capacities, it makes sense to

teach them how to turn their weakness into a strength (Maldonado and Spiegel,

1995). Hypnosis can be used formally both as a diagnostic tool and for

therapeutic purposes. The hypnotic state can be seen as a controlled form of

dissociation (Nemiah, 1985). Hypnosis is useful in the treatment of these

patients, first in determining whether they have a dissociative disorder, and

second in providing rapid access to these dissociated states. When used by the

therapist in the context of treatment, it can demonstrate to patients the

amount of control they have over this state, which they normally experience as “automatic

and unpredictable”. This not only serves to teach patients how to control

dissociation but also allows them to establish a process of communication that

will eventually lead to a reduction in spontaneous dissociative symptoms.

Therapists must remember that many of these patients have suffered physical,

emotional, or sexual abuse. It is imperative that we recognize and take account

of the impact of whatever trauma occurred and help patients work through their

reactions to it, as in the case of PTSD. Recognizing and teaching patients with

dissociative disorders how to master their capacity to dissociate are among the

most important psychotherapeutic tasks in the course of their treatment

(Maldonado and Spiegel, 2002a; Maldonado et

al., 2000).

We can

make use of hypnotic techniques as a way to help patients access repressed and

dissociated memories. Teaching patients to use self-hypnosis allows them to

obtain a sense of control over their symptoms and eventually their lives. The

repression or dissociation of traumatic events and the realities that surround

them may serve a defensive pur-pose of avoiding painful affect associated with

the memories. The memories are there, either transformed or interspersed with

fantasy. Our approach to the treatment of these victims is directed at helping

them acknowledge the extent of the emo-tional pain caused by the trauma. Then,

through therapy, we can assist in the development of mature and adequate coping

mechanisms that will allow the patient to place the experi-ence into proper

perspective. The goal is to allow the patient to come to terms with the trauma

and to redefine herself or himself in view of the past, but with a firm hold on

the reali-ties of the present.

Dissociation

as a defense serves a dual purpose. It rep-resents an effort to preserve some

form of control, safety and identity when faced with overwhelming stress. At

the same time, victims use it in an attempt to separate themselves from the

full impact of the trauma. Unfortunately, these individuals may ward off

memories of the trauma so well that they may act as if it is not happening and

later as if it never happened. Some individuals can so effectively repress

traumatic memories that they become unable consciously to work through them. As

a consequence, they are unable to put the facts surrounding the events

associated with the trauma into perspective, but slowly, the dissociated

feel-ings and memories leak into consciousness. This creates some of the

classic symptoms associated with PTSD and DID, such as flashbacks or intrusive

thoughts.

The

advantage of using hypnosis comes from the facilita-tion of the recovery of

affect or memories, the ability to dis-sociate memories from cognition, and the

speed with which the process is achieved. Finally, because of the relationship

between a history of childhood abuse and trance, these patients are usually

highly hypnotizable (Chu and Dill, 1990; Hilgard, 1984; Nash and Lynn, 1986;

Putman, 1993; Spiegel, 1988, 1990; Spiegel et

al., 1988).

Many

former victims of childhood abuse may unknow-ingly use their hypnotic

capacities to keep out of awareness the content of traumatic memories and in

effect create different de-grees of psychiatric illness (Sanders and Giola,

1991; Spiegel, 1984, 1986, 1989; Spiegel et

al., 1988; Terr, 1991). Teaching these patients self-hypnosis is a way of

turning a weakness into a strong tool for self-mastery and control. The

controlled use of hypnosis, then, becomes a way systematically to access

previously dissoci-ated material.

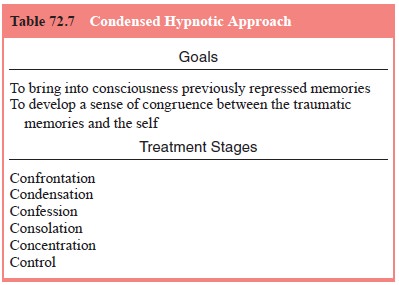

The Condensed Hypnotic Approach

The use

of hypnosis in the treatment of PTSD and disso-ciative disorders can be

conceptualized as having two major goals, which can be achieved by the use of

six different tech-niques (Maldonado and Spiegel, 1994, 1995, 2002b; Spiegel,

1992) (Table 72.7). The goals are to bring into consciousness previously repressed memories and to develop a sense

of congruence between memories

associated with the traumatic experience

and current self-images. By making conscious pre-viously repressed memories,

the patient has the opportunity to understand, accept and restructure them.

These goals are achieved by working through six treatment stages:

confronta-tion, condensation, confession, consolation, concentration and

control.

First the

patient must confront the trauma.

The therapist helps the patient recognize and understand the factors involved

in the development of the symptoms for which help is now being

sought.

Hypnosis is then used to help the patient condense

the traumatic memories. The hypnotic experience can be used to define a

particularly frightening memory during the revision of the patient’s history,

which summarizes or condenses the main conflicts. The focused concentration

achieved during the hypnotic state not only can facilitates recall of traumatic

material but also helps place boundaries around it. After memories are

recovered, we can help patients restructure them and even “become aware of

things you did at the moment of trauma to survive”. Once memories are

recovered, patients usually need to confess

feelings and experiences of which they are profoundly ashamed. These are usually things that they may have told no one

else before; in fact, they have been running from them all their lives. At this

time, the therapist must convey a sense of “being present” for the patient

while remaining as neutral as possible. This is followed by the stage of consolation. Here, the therapist needs

to be emotionally available to the patient. This stage must be carried on with

caution and in a most professional manner. Therapists should be aware that the

body and emotional boundaries of these patients may have been violated in the

past. Then comes the stage of concentration.

This component of the trance experience allows patients to have access or “turn

on” the traumatic memories during the psychotherapeutic session and then “shut

them off ” once the work has been done. During the final stage, the patient

comes to define herself or himself as being in control again.

The

underlying principle to remember is that the most damaging effect of

overwhelming trauma is that it renders its vic-tims defenseless. Because of the

lack of physical and emotional control, patients activate dissociative defenses

in an attempt to master their experiences. By using self-hypnosis, the

therapist can model and teach the patient to regain control over her or his

memories. Patients must be encouraged to remember as much as they feel is safe

to remember at a given time. The goal is that pa-tients learn how to think

about traumatic experiences, rather than negating their existence. The use of

self-hypnosis teaches patients that they are in control of their experiences.

Patients must dispel the magical beliefs that therapists “can take away the

memories”. Rather, by modeling this sense of trust in their therapists,

patients learn to trust themselves. They relearn trust in their own feelings

and perceptions.

The challenge in treating victims of abuse is to achieve a new sense of unity within the patient after the initial fragmentation caused by the traumatic experience. Overwhelming trauma tends to cause sudden and radical discontinuities in consciousness, which leaves the victims with a polarized view of themselves in-volving, on one hand the old self (before the trauma) and, on the other, the helpless, defenseless and traumatized victim. Our goal is to find ways to integrate these two aspects of the self. Here, the patient’s task is to acknowledge and place into perspective painful life events, thereby making them acceptable to conscious awareness.

One of

the advantages of the use of hypnosis is that the affect elicited can be so

powerful that most patients do not need to remember every single event of abuse

or trauma. In fact, through the use of hypnosis, the therapist may help the

patient consolidate the memories in a constructive way, thus facilitating

recovery. After a condensation of the traumatic experiences, patients become

ready to accept the victimized self. Instead of continuing the self-blame and

shame because of what happened to them, they can learn to acknowledge and even

thank themselves for what they did to survive. This restructuring allows them

to shift their perception of self, changing their self-image from that of a

victim to that of a survivor.

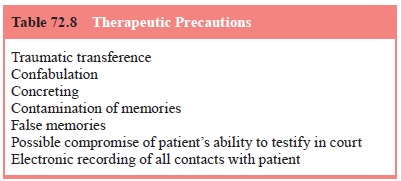

Therapeutic Precautions Therapeutic

precautions are shown in Table 72.8.

The strength of transference during the psycho-therapy of trauma victims is

enormous. The use of hypnosis does not prevent development of a transference

reaction; it may actually facilitate its emergence earlier than in regular

therapy owing to the intensity with which the material is expressed and

memories are recovered (Maldonado and Spiegel, 1994, 1995, 2002b).

Reliving

the traumatic experience along with the pa-tient may allow a special feeling of

“being there with them” at the moment of trauma. This allows the therapist to

provide guidance, support, protection and comfort as the patient goes through

the difficult path of reprocessing traumatic memo-ries. On the other hand, this

kind of traumatic transference

between the therapist and the victim of sexual assault is dif-ferent in the

sense that the feelings transferred are related not so much to early object

relationships but to the abuser or cir-cumstances that are associated with the

trauma (Spiegel, 1992). Instead of seeing this expressed anger at the therapist

as a form of negative transference reaction, we should explore the pos-sibility

that this may be a healthy attempt for the patient to ex-perience anger toward

the perpetrator. As therapists, we should not minimize or shut off these

feelings. This will only confirm the patient’s former perception that there was

something wrong with him or her for having these feelings, which will probably

activate further use of primitive defenses, including dissocia-tion or acting

out.

A more

serious complication of the use of hypnosis with trauma victims is the possible

creation of false memories.

Hypnosis, with its heightened sense of concentration, allows the patient to

focus intensely on a given time or place, en-hancing memory recall. The

principle of state-dependent memory also makes it plausible that the mere

entrance into this trance state can facilitate retrieval of memories associated

with a similar state of mind that may have occurred during the trauma and

subsequent flashbacks. However, not every mem-ory recovered with the use of

hypnosis is necessarily true. Hypnosis can facilitate improved recall of true

as well as con-fabulated material (Dywan and Bowers, 1983). Suggestibility is

increased in hypnosis, and information can be implanted or imagined and

reported as verdict (Laurence and Perry, 1983; McConkey, 1992). Because of

this, therapists are warned about “believing” everything a patient is able to

recall. Just as we use therapeutic judgment to analyze and interpret our

patients’ (nontraumatic) childhood memories, fantasies and dreams, so should we

treat hypnotically recovered material with caution.

To this

date, no evidence proves that the patient’s con-frontation with alleged

perpetrators of childhood abuse or pursuit of legal retribution toward the

perpetrator provides any therapeutic benefit. As therapists, we cannot be

certain of which memories are real, which are completely confabu-lated, and

which are a combination of both. Because of this, we should not encourage our

patients to take legal actions. If, on the other hand, our patients insist in

pursuing this avenue, it is our duty to warn them of our concerns but to be

support-ive of whatever final decision they make. Certainly we will do a

service to our patients if we inform them of all the legal ramifications that

the use of hypnosis, or any other form of memory enhancement, may have for

their defense, including their ability to testify in court or to use the

material recovered by such techniques.

Related Topics