Chapter: Basic & Clinical Pharmacology : Clinical Use of Antimicrobial Agents

Antimicrobial Prophylaxis

ANTIMICROBIAL PROPHYLAXIS

Antimicrobial agents

are effective in preventing infections in many settings. Antimicrobial

prophylaxis should be used in circum-stances in which efficacy has been

demonstrated and benefits outweigh the risks of prophylaxis. Antimicrobial

prophylaxis may be divided into surgical prophylaxis and nonsurgical

prophylaxis.

Surgical Prophylaxis

Surgical wound

infections are a major category of nosocomial infections. The estimated annual

cost of surgical wound infections in the United States is $1.5 billion.

The National Research

Council (NRC) Wound Classification Criteria have served as the basis for

recommending antimicrobial prophylaxis. NRC criteria consist of four classes

[see Box: National Research Council (NRC) Wound Classification Criteria].

The

Study of the Efficacy of Nosocomial Infection Control (SENIC) identified four

independent risk factors for postopera-tive wound infections: operations on the

abdomen, operations lasting more than 2 hours, contaminated or dirty wound

classifi-cation, and at least three medical diagnoses. Patients with at least

two SENIC risk factors who undergo clean surgical procedures have an increased

risk of developing surgical wound infections and should receive antimicrobial

prophylaxis.

Surgical

procedures that necessitate the use of antimicrobial prophylaxis include

contaminated and clean-contaminated opera-tions, selected operations in which

postoperative infection may be catastrophic such as open heart surgery, clean

procedures that involve placement of prosthetic materials, and any procedure in

an immunocompromised host. The operation should carry a signifi-cant risk of

postoperative site infection or cause significant bacte-rial contamination.

General principles of

antimicrobial surgical prophylaxis include the following:

1. Theantibiotic

should be active against common surgical wound pathogens; unnecessarily broad

coverage should be avoided.

2.

The antibiotic should have proved efficacy in clinical trials.

3. The antibiotic must

achieve concentrations greater than the MIC of suspected pathogens, and these

concentrations must be present at the time of incision.

4. The shortest

possible course—ideally a single dose—of the most effective and least toxic

antibiotic should be used.

5. The newer

broad-spectrum antibiotics should be reserved for therapy of resistant

infections. If all other factors are equal, the least expensive agent should be

used.

The proper selection

and administration of antimicrobial pro-phylaxis are of utmost importance.

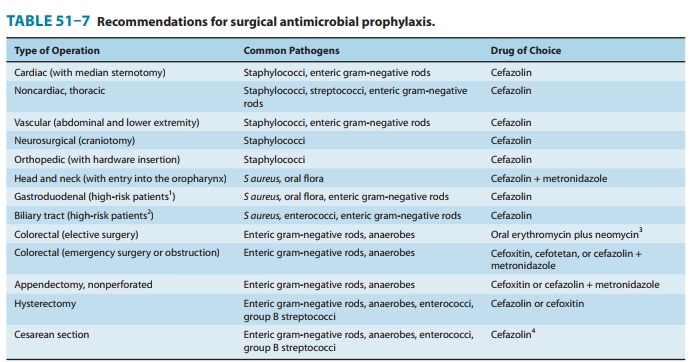

Common indications for sur-gical prophylaxis are shown in Table 51–7. Cefazolin

is the prophylactic agent of choice for head and neck, gastroduodenal, biliary

tract, gynecologic, and clean procedures. Local wound infection patterns should

be considered when selecting antimicro-bial prophylaxis. The selection of

vancomycin over cefazolin may be necessary in hospitals with high rates of

methicillin-resistant Saureus or S epidermidis infections. The

antibiotic should be presentin adequate concentrations at the operative site

before incision and throughout the procedure; initial dosing is dependent on

the volume of distribution, peak levels, clearance, protein binding, and

bioavailability. Parenteral agents should be administered dur-ing the interval

beginning 60 minutes before incision; administra-tion up to the time of

incision is preferred. In cesarean section, the antibiotic is administered

after umbilical cord clamping. If short-acting agents such as cefoxitin are

used, doses should be repeated if the procedure exceeds 3–4 hours in duration.

Single-dose pro-phylaxis is effective for most procedures

and results in decreased toxicity and antimicrobial resistance.Improper

administration of antimicrobial prophylaxis leads to excessive surgical wound

infection rates. Common errors in anti-biotic prophylaxis include selection of

the wrong antibiotic,

National Research Council (NRC) Wound

Classification Criteria

Clean: Elective, primarily closed procedure; respiratory,

gas-trointestinal, biliary, genitourinary, or oropharyngeal tract not entered;

no acute inflammation and no break in technique; expected infection rate ≤ 2%.

Clean contaminated: Urgent or emergency case that is oth-erwise clean; elective,

controlled opening of respiratory, gas-trointestinal, biliary, or oropharyngeal

tract; minimal spillage or minor break in technique; expected infection rate ≤ 10%.

Contaminated: Acute nonpurulent inflammation; majortechnique break or major

spill from hollow organ; penetrat-ing trauma less than 4 hours old; chronic

open wounds to be grafted or covered; expected infection rate about 20%.

Dirty: Purulence or abscess; preoperative perforation ofrespiratory, gastrointestinal, biliary, or oropharyngeal tract; penetrating trauma more than 4 hours old; expected infec-tion rate about 40%.

Nonsurgical Prophylaxis

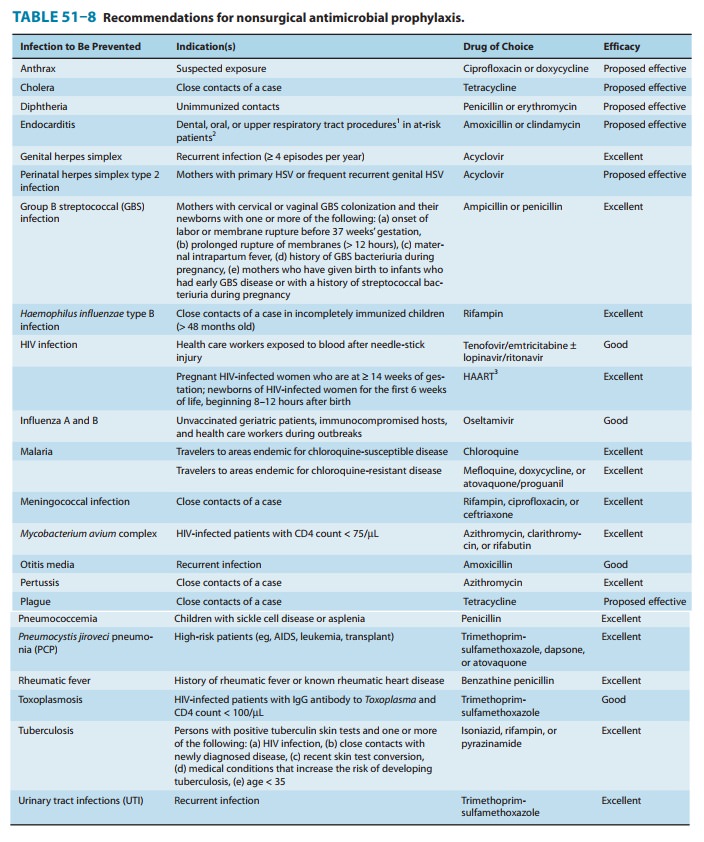

Nonsurgical

prophylaxis includes the administration of antimicro-bials to prevent

colonization or asymptomatic infection as well as the administration of drugs

following colonization by or inocula-tion of pathogens but before the

development of disease. Nonsurgical prophylaxis is indicated in individuals who

are at high risk for temporary exposure to selected virulent pathogens and in

patients who are at increased risk for developing infection because of

under-lying disease (eg, immunocompromised hosts). Prophylaxis is most

effective when directed against organisms that are predictably sus-ceptible to

antimicrobial agents. Common indications and drugs for nonsurgical prophylaxis

are listed in Table 51–8.

Related Topics