Chapter: Clinical Anesthesiology: Anesthetic Management: Anesthesia for Trauma & Emergency Surgery

Anesthesia for Primary Survey

PRIMARY SURVEY

Airway

Increasingly, emergency medical technician–

paramedics and flight nurses are trained to intu-bate patients in the

prehospital environment. More providers capable of airway management in the

critically ill or injured patient are now available to intervene in the

hospital setting as well. As a result, the anesthesiologist’s role in providing

initial trauma resuscitation has diminished in North America. This also means

that when called upon to assist in airway management in the emergency

department, anes-thesia providers must expect a challenging airway, as routine

airway management techniques likely have already proved unsuccessful.

There are three important aspects of airway management in the initial evaluation

of a trauma patient: (1) the need for basic life support; (2) the presumed

presence of a cervical spinal cord injuryuntil proven otherwise; and (3) the

potential for failed tracheal intubation. Effective basic

life support prevents hypoxia and hypercapnia from contributing to the

patient’s depressed level of consciousness. When hypercarbia produces a

depressed level of consciousness, basic airway

interventions oftenlessen the

need for endotracheal

intubation asarterial carbon

dioxide levels return to normal.

Finally, all trauma patients should be pre-sumed to have “full” stomachs

and an increased risk for pulmonary aspiration

of gastric contents. Assisted ventilation should be performed with vol-umes

sufficient to provide chest rise. Some clinicians will apply cricoid pressure,

although the efficacy of this maneuver is controversial.

Cervical spine injury is presumed in any

trauma patient complaining of neck pain, orwith any significant head injury,

neurological signs or symptoms suggestive of cervical spine injury, or

intoxication or loss of consciousness. The applica-tion of a cervical collar

(“C-collar”) before trans-port to protect the cervical spinal cord will limit

the degree of cervical extension that is ordinarily expected for direct

laryngoscopy and tracheal intu-bation. Alternative devices (eg,

videolaryngoscopes, fiberoptic bronchoscopes) should be immediately available.

The front portion of the C-collar can be removed to facilitate tracheal

intubation as long as the head and neck are maintained in neutral posi-tion by

a designated assistant maintaining manual in-line stabilization.

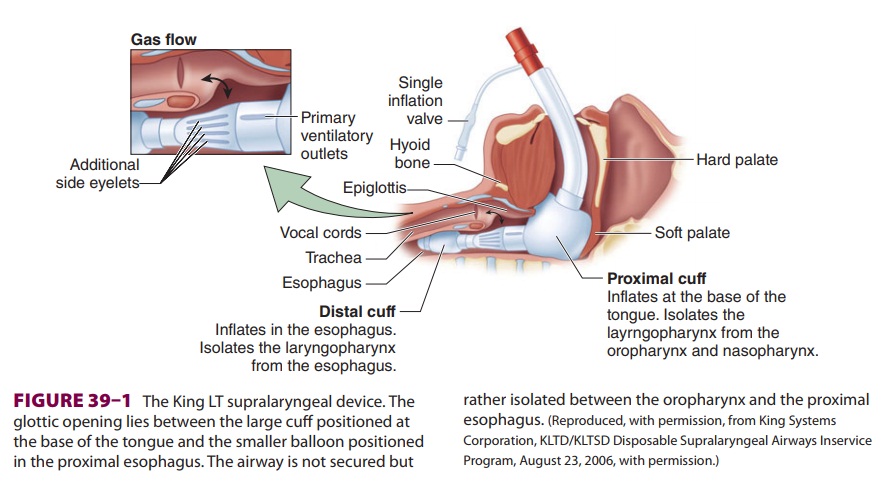

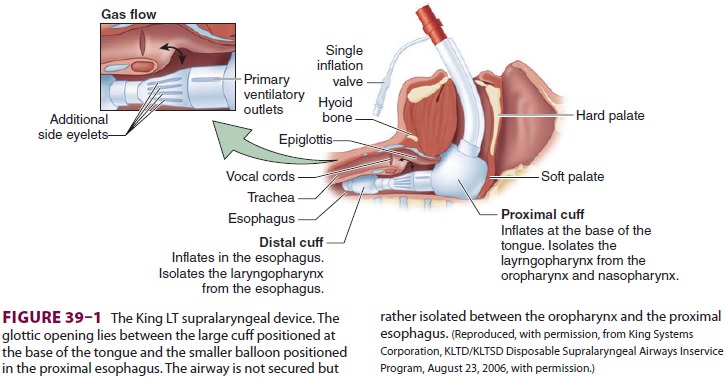

Alternative devices for airway management

(eg, esophageal–tracheal Combitube, King supra-laryngeal device) may be used if

direct laryngos-copy has failed, or in the prehospital environment. These

devices, blindly placed into the airway, isolate the glottic opening between a

large inflatable cuff positioned at the base of the tongue and a distal cuff

that most likely rests in the proximal esopha-gus (Figure 39–1). The prolonged presence of these devices in the airway has been

associated with glos-sal engorgement resulting from the large, proximal cuff

obstructing venous outflow from the tongue, and in some cases, tongue

engorgement has been sufficiently severe to warrant tracheostomy prior to their

removal. There is limited evidence that pre-hospital airway management in

trauma patients improves patient outcomes; however, failed tracheal intubation

in the prehospital environment certainly exposes patients to significant

morbidity.

Airway management of the trauma patient is uneventful in most

circumstances, and

cricothyroidotomy or tracheostomy is rarely required to secure the

trauma airway. When trauma significantly alters or distorts the facial or upper

airway anatomy to the point of impeding adequate mask ventilation, or when

hemorrhage into the air-way precludes the patient from lying supine, elective

cricothyroidotomy or tracheostomy should be con-sidered before any attempts are

made to anesthetize or administer neuromuscular blocking agents to the patient

for orotracheal intubation.

Breathing

In the multiple-injury patient, providers

should maintain a high level of suspicionfor pulmonary injury that could evolve

into a ten-sion pneumothorax when mechanical ventilation is initiated.

Attention must be paid to peak inspi-ratory pressure and tidal volumes

throughout the initial resuscitation. Pulmonary injury may not be immediately

apparent upon the patient’s arrival at the hospital, and abrupt cardiovascular

collapse shortly after instituting mechanical ventilation may announce the

presence of a pneumothorax. This should be managed by disconnecting the patient

from mechanical ventilation and performing bilat-eral needle

thoracostomy (accomplished by insert-ing a 14-gauge intravenous catheter into

the second interspace in the midclavicular line), and then by thoracostomy tube

insertion. Inspired oxygen con-centrations of 100% are used routinely in this

early phase of resuscitation.

Circulation

During the primary trauma patient survey,

signs of a pulse and blood pressure are sought. Unless the trauma patient

arrives at the hospital other than by ambulance, the resuscitation team will

likely have received information about the patient’s vital signs from the

prehospital personnel (emergency medi-cal technicians, flight nurses). The

absence of a pulse following trauma is associated with dismal chances of

survival. The ACS Committee on Trauma no lon-ger endorses the use of emergency

thoracotomy in treating patients without blood pressure or palpable pulse

following blunt trauma, even in the

presence of organized cardiac activity, given the lack of evidence supporting

survival following this intervention.Retrospective review of emergency

thoracotomy in Europe failed to demonstrate resuscitation benefit of this

procedure following either blunt or penetrating trauma in the setting of

cardiac arrest. In the setting of chest trauma without detectable blood

pressure or palpable pulse, current practice supports reserving resuscitative

thoracotomy for patients who experi-ence penetrating

trauma and have preserved, orga-nized cardiac rhythms or other signs of life.

In light of these recommendations, prompt placement of bilateral chest

tubes and adminis-tration of a 500–1000 mL fluid bolus should be implemented in

the pulseless victim of penetrating trauma. If return of spontaneous

circulation does not occur promptly, more aggressive interventions are not

indicated and resuscitation efforts can be terminated.

Neurological Function

Once the presence of circulation is

confirmed, a brief neurological examination is conducted. Level of

con-sciousness, pupillary size and reaction, lateralizing signs suggesting

intracranial or extracranial inju-ries, and indications of spinal cord injury

are quickly evaluated. As noted earlier, hypercarbia often causes depressed

neurological responsiveness following trauma; it is effectively corrected with

basic life sup-port interventions. Additional causes of depressed neurological

function—eg, alcohol intoxication, effects of illicit or prescribed

medications, hypogly-cemia, hypoperfusion, or brain or spinal injury— must also

be addressed. Mechanisms of injury must be considered as well as exclusion of other

factors in determining the risk for central nervous system trauma. Persistently

depressed levels of conscious-ness should be considered a result of central

nervous system injury until disproved by diagnostic studies.

Injury Assessment:Minimizing Risks of Exposure

The patient must be fully exposed and examined in order to adequately

assess the extent of injury, and this physical exposure increases the risk of

hypo-thermia. The presence of shock and intravenous fluid therapy also place

the trauma patient at great risk for developing hypothermia. As a result, the

resuscitation bay must be maintained at near body temperature, all fluids

should be warmed during administration, and the use of forced air patient

warmers, either below or covering the patient, should be utilized.

Related Topics