Chapter: Clinical Anesthesiology: Anesthetic Management: Anesthesia for Patients with Respiratory Disease

Anesthesia : Pulmonary Risk Factors

PULMONARY RISK FACTORS

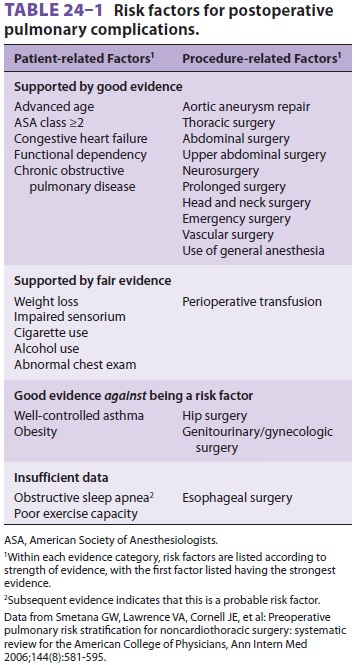

Certain risk factors (Table 24–1) may

predispose patients to postoperative pulmonary complica-tions. The incidence of

atelectasis, pneumonia,pulmonary embolism, and respiratory failure fol-lowing

surgery is quite high, but varies widely (from 6% to 60%), depending on the

patient population studied and the surgical procedures performed. The two

strongest predictors of complications seem to be operative site and a history of

dyspnea, which correlate with the degree of preexisting pulmonary disease.

The association between smoking and

respi-ratory disease is well established; abnormalities in maximal

midexpiratory flow (MMEF) rates are often demonstrable well before symptoms of

COPD appear. Although abnormalities can be demon-strated on pulmonary function

tests (PFTs), because most patients who smoke do not have PFTs per-formed

preoperatively, it is best to assume that such patients have some degree of

pulmonary compro-mise. Even in normal individuals, advancing age is associated

with an increasing prevalence of pul-monary disease and an increase in closing

capac-ity. Obesity decreases functional residual capacity (FRC), increases the

work of breathing, and predis-poses patients to deep venous thrombosis.

Thoracic and upper abdominal surgical proce-dures can have marked effects on pulmonary func-tion. Operations near the diaphragm often result in diaphragmatic dysfunction and a restrictive ventilatory defect . Upper abdominal procedures consistently decrease FRC (60% to 70%); the effect is maximal on the first postoperative day and usually lasts 7–10 days. Rapid shallow breathing with an ineffective cough caused by pain (splinting), a decrease in the number of sighs, and impaired mucociliary clearance lead to microatelectasis and loss of lung volume. Intrapulmonary shunting pro-motes hypoxemia. Residual anesthetic effects, the recumbent position, sedation from opioids, abdomi-nal distention, and restrictive dressings may also be contributory. Complete relief of pain with regional

anesthesia can decrease, but does not

completely reverse these abnormalities. Persistent microatelec-tasis and

retention of secretions favor the develop-ment of postoperative pneumonia.

Although many adverse effects of general

anes-thesia on pulmonary function have been described, the superiority of

regional over general anesthesia in patients with pulmonary impairment is not

firmly established.

Because of the prevalence of smoking and

obe-sity, many patients may be at increased risk of devel-oping postoperative

pulmonary dysfunction. The risk of complications increases if the patient is

hav-ing a thoracotomy or laparotomy, even if the patient has no risk factors.

Patients with known disease should have their pulmonary function optimized

preoperatively, with careful consideration given to the choice of general

versus regional anesthesia.

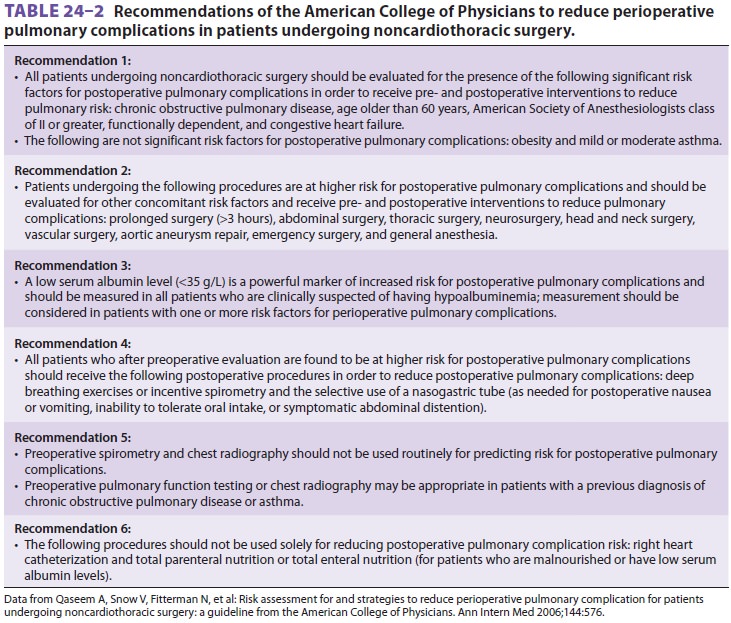

The American College of Physicians has

estab-lished guidelines to assist in the preoperative assess-ment of patients

with pulmonary disease (see Table 24–2).

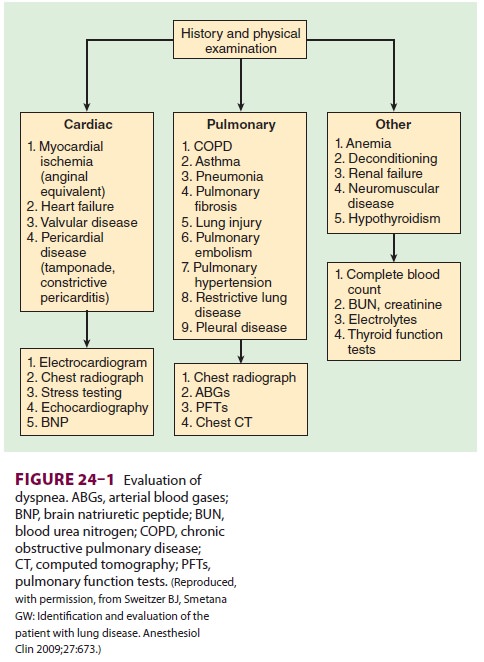

When patients with a history of dyspnea

present without the benefit of a previous workup, the differ-ential diagnosis

can be quite broad and may include both primary pulmonary and cardiac

pathologies. Diagnostic approaches to evaluating such patients are summarized

in Figure24–1.

Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

Obstructive

and restrictive breathing are the two most common abnormal patterns, as

determined by PFTs. Obstructive lung diseases are the most com-mon form of

pulmonary dysfunction. They include asthma, emphysema, chronic bronchitis,

cystic fibrosis, bronchiectasis, and bronchiolitis. The pri-mary characteristic

of these disorders is resistance to airflow. An MMEF of <70% (forced

expiratory flow [FEF25–75%]) is often the only abnormality early in

the course of these disorders. Values for FEF25–75% in adult males

and females are normally >2.0

and >1.6

L/sec, respectively. As the disease progresses, both forced expiratory volume

in 1 sec (FEV1) and the FEV1/FVC (forced vital capacity)

ratio are less than 70% of the predicted values.

Elevated

airway resistance and air trap-ping increase the work of breathing; respiratory

gas exchange· is·

impaired because of ventilation/ perfusion (V/Q) imbalance. The predominance of

expiratory airflow resistance results in air trap-ping; residual volume and

total lung capacity (TLC) increase. Wheezing is a common finding and

repre-sents turbulent airflow. It is often absent with mild obstruction that

may be manifested initially only by prolonged exhalation. Progressive

obstruction typi-cally results first in expiratory wheezing only, and then in

both inspiratory and expiratory wheezing. With marked obstruction, wheezing may

be absent when airflow has nearly ceased.

Related Topics