Chapter: Modern Medical Toxicology: Corrosive(Caustic) Poisons: Alkalis and Other Caustics

Alkalis - Corrosive(Caustic) Poisons

Alkalis

and Other Caustics

ALKALIS

Alkalis

commonly encountered in poisoning include ammonia (usually in the form of

ammonium hydroxide), carbonates of sodium and potassium, and hydroxides of

sodium, potassium, and calcium. Sodium hypochlorite is also increasingly being

implicated.

Physical Appearance

Most of these occur as white powders

or colourless solutions. Ammonia gas is colourless with a pungent, choking

odour.

Uses

·

Ammonia

gas—Smelling salts.*

·

Ammonium

hydroxide (32.5% ammonia)—Paint,

oil, and dirt remover, refrigerant.

·

Sodium

hydroxide (caustic soda)—Drain

cleaner, oven cleaner. Potassium

hydroxide (caustic potash)—Drain

cleaner, hearing aid batteries.

·

Sodium

carbonate (washing soda)—Household

cleaning agent, detergent.

·

Potassium

carbonate—Household cleaning agent.

·

Sodium

hypochlorite—Household bleach.

Usual Fatal Dose

·

About 10 to 15 gm for most alkalis.

·

About 15 to 20 ml for ammonia.

Mode of Action

Locally,

alkalis produce liquefaction necrosis which results in extensive penetrating

damage because of saponification of fats and solubilisation of proteins.

Production of ulcers is common which may persist for several weeks. Oesophagus

is more severely affected than the stomach in contrast to acids.

Clinical Features

Corrosion of GI mucosa with greyish

pseudomembrane formation. Oesophagus is often severely affected resulting in

dysphagia, vomiting, drooling, and haematemesis. Stridor is an important

indicator of severe oesophageal injury.

There

are four categories of alkali induced oesophagitis:

a. Non-ulcerative oesophagitis—from

ingestion of mildirritants, resulting in 1st degree burns.

b.Mild ulcerative oesophagitis—from

ingestion of weakbases. 2nd degree burns are produced. Strictures may develop.

c.Severe ulcerative oesophagitis—from

ingestion ofstrong bases. There is severe dysphagia with vomiting which may

subside after 2 to 3 days only to reappear as slowly progressive dysphagia

after 4 to 6 weeks due to stricture formation. This may lead to total

obstruction.

d.Oesophagitis with complications—apart

fromoesophagitis, there are complications such as medi-astinitis, perforation,

pericarditis, pulmonary oedema, laryngeal obstruction, etc.

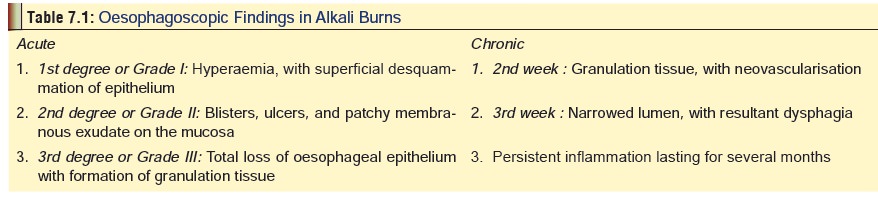

It

is important to perform oesophagoscopy and make accurate assessment as to the

extent of local injury (Table 7.1).

Contraindications to oesophagoscopy include upper airway obstruction and GI

perforation.

Abdominal

pain, diarrhoea, tenesmus. Skin involvement results in greyish, soapy, necrotic

areas without charring.

Eye

involvement can produce serious complications, and constitutes an

ophthalmologic emergency.

Ammonia

ingestion causes manifestations which are essen-tially similar to those seen

with other alkalis, but respiratory symptoms are commonly super-added due to

inhalation of fumes while swallowing.

Diagnosis

1.In stomach contents:

a. White, solid, slimy lumps,

flakes, or granules.

b.Turns litmus paper blue.

c.Becomes warm on addition of water.

d.If exposed to air, becomes moist

and gets dissolved.

e.Soapy or slimy feeling when

touched with fingers.

f.Sharp penetrating odour in the

case of ammonia.

2.Platinum wire flame test: Touch platinum wire to theunknown

substance and then place it in a flame. Sodium gives an intense persistent

yellow flame. Potassium gives a deep purple flame.

3.Fume test for ammonia: Place an open bottle of

concen-trate Hcl near a sample of stomach contents, aspirate, or vomitus.

Copious white fumes of ammonium chloride will emanate if ammonia is present.

The test can also be done to detect the presence of ammonia in the atmosphere.

Treatment

·

Respiratory distress (especially in the case of ammonia) may

require endotracheal intubation, cricothyroidotomy, or tracheostomy, depending

on severity. Oxygen must be administered as necessary.

·

Diluents such as milk or water may be given as a first aid

measure for alkali ingestion (no more than one or two glasses for an adult). If

more than one hour has elapsed, this is usually not efficacious.

·

The following are absolutely contraindicated : emesis,gastric

lavage, catharsis, and activated

charcoal. Withhold all oral feeds initially.

·

Assess fluid and electrolyte balance.

·

Watch for development of complications and attend to them

accordingly.

·

Some investigators recommend early surgical intervention and

use of an intraluminal stent in patients with 2nd or 3rd degree oesophageal

burns because perforation which requires surgical repair may otherwise be

missed. Others have suggested that if the serum pH is less than 7.20 (because

of lactic acidosis resulting from severe tissue necrosis), surgery should be

immediately undertaken.

·

If circumferential 2nd degree or 3rd degree burns of the

oesophagus are seen, exploratory laparotomy should be undertaken followed by

gastric resection and oesopha-gectomy, in case gastric necrosis is evident at

laparos-copy.

·

In the past, administration of corticosteroids was recom-mended

to prevent stricture formation which was based on animal studies. But today

most investigators appear to be of the opinion that high dose corticosteroid

therapy in caustic ingestion predisposes the patient to infection and

perforation as well as masks symptoms of devel-oping peritonitis or

mediastinitis, and hence should be avoided. However, steroids may be effective

in patients with dyspnoea, stridor, hoarseness, and other evidence of

respiratory compromise, and may decrease laryngotra-cheal oedema thereby

lessening respiratory dysfunction.

·

Use of prophylactic antibiotics is not recommended today.

Most investigators feel that antibiotics should be administered only if there

are signs of perforation or secondary infection.

·

An oesophagogram should be done at 3 weeks to evaluate the

formation of strictures. Patients should be instructed to seek medical

attention immediately when-ever they develop dysphagia.

·

Alkali injuries to the eye and skin should be irrigated

copiously with water or saline for at least 20 to 30 minutes. Ophthalmologic

consultation is mandatory. Topical antibiotics and steroids may help.

·

Patients who have suffered from stricture formation require

long-term endoscopic follow-up for the presence of neoplastic changes of the

oesophagus which may occur with a delay of several years or decades.

Autopsy Features

· Characteristic odour (in the case of

ammonia).

· Brownish or greyish staining of

skin.

· Inflammatory oedema with corrosion

and sliminess of the tissues of the oesophagus and stomach. The mucosa may be

brownish owing to formation of alkaline haematin.

·

Congestion of respiratory tract and pulmonary oedema

(especially in the case of ammonia).

Forensic Issues

·

Accidental poisoning occurs usually

by mistaking an alkali solution for water, lemonade, beer, etc., because of

careless storage of these chemicals in inadequately labeled, ordinary looking

bottles or jars.

·

Industrial accidents involving these

substances are reported from time to time.

·

Suicidal cases are occasionally

encountered. Homicides from time to time.

·

Suicidal cases are occasionally

encountered. Homicides are quite rare.

·

Ammonia may sometimes be sprayed or

thrown on a victim to facilitate robbery.

Related Topics