Chapter: Modern Pharmacology with Clinical Applications: Adrenocortical Hormones and Drugs Affecting the Adrenal Cortex

Adverse Effects

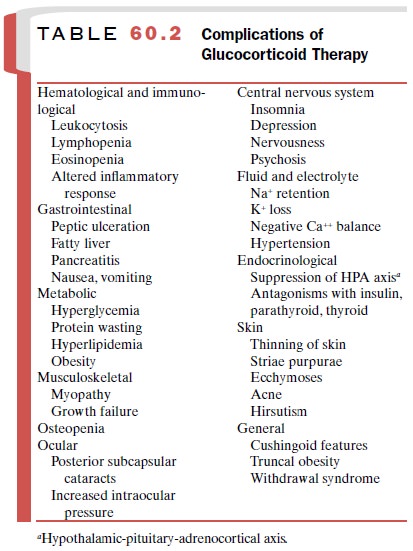

ADVERSE EFFECTS

General Considerations

Short-term glucocorticoid

therapy of life-threatening diseases, such as status asthmaticus, provides

dramatic improvement with few complications. However, when administered in pharmacological

doses for long periods, steroids generally produce serious toxic effects that

are extensions of their pharmacological actions. No route or preparation is

free from the diverse side effects (Table 60.2), although individuals receiving

comparable doses of glucocorticoids exhibit variations in side effects.

Glucocorticoids are

cautiously employed in various disease states, such as rheumatoid arthritis,

although they still should be regarded as adjunctive rather than primary

treatment in the overall management scheme. The toxic effects of steroids are

severe enough that a number of factors must be considered when their pro-longed

use is contemplated.

The first point is that

treatment with steroids is gen-erally palliative rather than curative, and only

in a very few diseases, such as leukemia and nephrotic syndrome, do

corticosteroids alter prognosis. One must also con-sider which is worse, the

disease to be treated or possi-ble induced hypercortisolism. The patient’s age

can be an important factor, since such adverse effects as hyper-tension are

more apt to occur in old and infirm individ-uals, especially in those with

underlying cardiovascular disease. Glucocorticoids should be used with caution

during pregnancy. If steroids are to be employed, pred-nisone or prednisolone

should be used, since they cross the placenta poorly.

Once steroid therapy is decided upon, the lowest possible dose that can provide the desired therapeutic effect should be employed. Relationships of dosage, du-ration, and host responses are essential elements in de-termining adverse effects. Increasing attention is being given to the use of lower doses of glucocorticoids in combination with other drugs that can have a synergis-tic effect on a given disease. Moreover, the lowered dose levels of steroid will minimize the side effects.

Osteoporosis

The most damaging and

therapeutically limiting ad-verse effect of long-term glucocorticoid therapy is

im-pairment of bone formation. This effect is associated with a decrease in

serum levels of osteocalcin, a marker of osteoblastic function. In fact, glucocorticoid adminis-tration is the most

common cause of drug-induced osteo-porosis. Most patients receiving chronic

steroid therapy develop osteoporosis,

particularly during the first year of therapy, and more than 50% will have a

bone frac-ture. Trabecular bone is particularly affected.

Systemic glucocorticoid

therapy increases the prob-ability of osteoporosis even with dosages

sufficiently low so as not to affect the hypothalamic–pituitary– adrenal axis.

By enhancing bone resorption and de-creasing bone formation, glucocorticoids

decrease bone mass and increase the risk of fractures. The overall ef-fects

appear to be due to direct actions of glucocorti-coids on osteoblasts and to

indirect effects, such as im-paired Ca++ absorption and a

compensatory increase in parathyroid hormone secretion. Inhibition of bone

growth is a well-known side effect of long-term systemic glucocorticoid therapy

in children with bronchial asthma, even in those receiving alternate-day

therapy. Glucocorticoids can also augment bone loss, decreasing testosterone

levels in men and estrogen levels in women by direct effects on the gonads and

inhibition of go-nadotropin release. Thus, patients taking glucocorti-coids can

also develop hypogonadism. It is recom-mended that all patients who receive

long-term glucocorticoid treatment should have measurements of bone density,

gonadal steroids, vitamin D, and 24-hour urinary Ca++ . Deficiencies

in either testosterone or estradiol increase bone loss and should be corrected

if possible. Bisphosphonates (etidronate, alendronate, or risedronate) and

calcitonin, which inhibit bone resorp-tion, have become increasingly popular

for treating os-teoporosis.

The Infectious Process

Steroids can alter

host–parasite interactions, suppress fever, decrease inflammation, and change

the usual character of the symptoms produced by most infectious organisms.

There is a heightened susceptibility to seri-ous bacterial, viral, and fungal

infections. Local infec-tions may reactivate and spread, and infections

ac-quired during the course of therapy may become more severe and even more

difficult to recognize. By interfer-ing with fibroblast proliferation and

collagen synthesis, glucocorticoids cause dehiscence of surgical incisions,

increase risk of wound infection, and delay healing of open wounds. This

untoward effect of steroids may make it mandatory to administer antibiotics

with the steroids, especially when there is a history of a chronic infectious

process (e.g., tuberculosis). On the other hand, individuals with normal

defenses who are treated with low to moderate doses of glucocorticoids are not

at great risk of infection. While the incidence of infections has probably decreased

with the increased use of in-haled steroids and combination therapy, inhaled

steroids carry an increase in the incidence of oral can-didiasis that can be

reduced by using proper doses. Nevertheless, glucocorticoids are used to treat

herpes zoster, bacterial meningitis, and skin infections.

Effects on Gastric Mucosa

Steroid administration was

once thought to lead to the formation of peptic ulcers, with hemorrhage or

perfora-tion or reactivation of a healed ulcer. It is now realized that this

effect is principally observed in patients who have received concomitant

nonsteroidal antiinflamma-tory treatment. Since there is a minimal increase in

the incidence of ulcers in patients receiving glucocorticoid treatment alone,

prophylactic antiulcer regimens are usually not necessary.

Hyperglycemic Action

In about one-fourth to

one-third of the patients receiv-ing prolonged steroid therapy, the

hyperglycemic effects of glucocorticoids lead to decreased glucose tolerance,

decreased responsiveness to insulin, and even glyco-suria. Ketoacidosis occurs

very rarely. Pharmacological concentrations of steroids may precipitate frank

dia-betes in individuals who cannot produce the necessary additional insulin.

Mild hyperglycemia can often be managed with oral hypoglycemic agents. The

effects of glucocorticoids on hyperglycemia are usually reversed within 48

hours following discontinuation of steroid therapy. If glucocorticoid therapy

is continued for an extended period, the alterations of glucose metabolism and

the resulting hyperinsulinemia may lead to en-hanced cardiovascular risk.

Ophthalmic Effects

Glucocorticoids induce

cataract formation, particularly in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. An

increase in intraoc-ular pressure related to a decreased outflow of aqueous

humor is also a frequent side effect of periocular, topical, or systemic

administration. Induction of ocular hyperten-sion, which occurs in about 35% of

the general population after glucocorticoid administration, depends on the

spe-cific drug, the dose, the frequency of administration, and the

glucocorticoid responsiveness of the patient.

Central Nervous System Effects

Treatment with steroids may

initially evoke euphoria. This reaction can be a consequence of the salutary

ef-fects of the steroids on the inflammatory process or a di-rect effect on the

psyche. The expression of the unpre-dictable and often profound effects exerted

by steroids on mental processes generally reflects the personality of the

individual. Psychiatric side effects induced by gluco-corticoids may include

mania, depression, or mood dis-turbances. Restlessness and early-morning

insomnia may be forerunners of severe psychotic reactions. In such situations,

cessation of treatment might be consid-ered, especially in patients with a history

of personality disorders. In addition, patients may become psychically

dependent on steroids as a result of their euphoric ef-fect, and withdrawal of

the treatment may precipitate an emotional crisis, with suicide or psychosis as

a conse-quence. Patients with Cushing’s syndrome may also ex-hibit mood

changes, which are reversed by effective treatment of the hypercortisolism.

The hippocampus is a

principal neural target for glu-cocorticoids. It contains high concentrations

of gluco-corticoid and mineralocorticoid receptors and has marked sensitivity

to these hormones.

Fluid and Electrolyte Disturbances

The normal subject may retain sodium and water

during steroid therapy, although the synthetic steroid analogues represent a

lesser risk in this regard. Pred-nisolone produces some edema in doses greater

than 30 mg; triamcinolone and dexamethasone are much less li-able to elicit

this effect. Glucocorticoids may also pro-duce an increase in potassium

excretion. Muscle weak-ness and wasting of skeletal muscle mass frequently

accompany this potassium-depleting action. The expan-sion of the extracellular

fluid volume produced by steroids is secondary to sodium and water retention.

However, the presence of specific steroid receptors in vascular smooth muscle suggests

that glucocorticoids are also more directly involved in the regulation of blood

pressure. The major adverse effects of glucocorti-coids on the cardiovascular

system include dyslipidemia and hypertension, which may predispose patients to

coronary artery disease. A separate entity, steroid my-opathy, is also improved

by decreasing steroid dosage.

Pseudorheumatism

In certain patients, whose

large dosages of cortico-steroids for rheumatoid arthritis are gradually

dimin-ished, new symptoms develop that may be mistaken for a flare-up of the

joint disease. These can include emo-tional lability, fever, muscle aches, and

general fatigue. It is tempting to increase the dosage of steroid in this

sit-uation, but continued maintenance at the lower dosage with a subsequent

gradual decrease in the dose usually improves symptoms.

Additional Effects

Other side effects include

acne, striae, truncal obesity, deposition of fat in the cheeks (moon face) and

upper part of the back (buffalo hump), and dysmenorrhea. Topical administration

may produce local skin atrophy. In patients with AIDS who are treated with

glucocorti-coids, Kaposi’s sarcoma becomes activated or pro-gresses more

rapidly.

Iatrogenic Adrenal Insufficiency

In addition to the dangers

associated with long-term use of corticosteroids in supraphysiological

concentrations, withdrawal of steroid therapy presents problems. The

suppression of the hypothalamic–pituitary axis ob-served with modest doses and

short courses of gluco-corticoid therapy is usually readily reversible.

However, steroid therapy with modest to high doses for 2 weeks or longer will

depress hypothalamic and pituitary activ-ity and result in a decrease in

endogenous adrenal steroid secretion and eventual adrenal atrophy. These

patients have a limited ability to respond to stress and an enhanced

probability that shock will develop. Long-acting steroids, such as

dexamethasone and betametha-sone, suppress the hypothalamic–pituitary axis more

than do other steroids. The

functional state of the hypo-thalamic–pituitary axis can be evaluated by tests

involv-ing basal plasma cortisol determinations, low and high doses of

cosyntropin (peptide fragment of corti-cotrophin), insulin hypoglycemia,

metyrapone, and corticotrophin-releasing hormone.

Glucocorticoids are not

withdrawn abruptly but are tapered. The doses are altered so that the condition

being treated will not flare up and recovery of the hypothalamic–pituitary axis

will be facilitated. Tapering the dose may reduce the potential for the development

of Addison-like symptoms associated with steroid with-drawal. Alternate-day

therapy will relieve the clinical manifestations of the inflammatory diseases

while allow-ing a day for reactivation of endogenous corticosteroid output,

thereby causing less severe and less sustained hypothalamic–pituitary

suppression. This is feasible with doses of shorter-acting corticosteroids,

such as pred-nisolone. The usual daily dose is doubled and is given in the

early morning to simulate the natural circadian vari-ation that occurs in

endogenous corticosteroid secretion. The benefits of alternate-day therapy are

seen only when steroids are used for a long period and are partic-ularly useful

for tapering the dose of glucocorticoid.

Although not always

predictable, the degree to which a given corticosteroid will suppress pituitary

activity is re-lated to the route of administration, the size of the dose, and

the length of treatment. The parenteral route causes the greatest suppression,

followed by the oral route, and finally topical application.

Hypothalamic–pituitary sup-pression also may result if large doses of a steroid

aero-sol spray are used to treat bronchial asthma. Patients given high

concentrations of steroids for long periods and subsequently exposed to undue stress

(e.g., severe infection, surgery) face the danger of adrenal crisis. These

patients must be given supplemental steroids to compensate for their lack of

adrenal reserve and to sus-tain them during the crisis.

Acute adrenal insufficiency

will, of course, occur from an abrupt cessation of steroid therapy. The

causa-tion of fever, myalgia, arthralgia, and malaise may be difficult to

distinguish from reactivation of rheumatic disease. Steroid treatment should be

reduced gradually over several months to avoid this potentially serious

problem. Also, continued suppression may be avoided by administering daily

physiological replacement doses (5 mg prednisone) until adrenal function is

restored. Although tapering of dose may not facilitate recovery of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal

axis, it may re-duce the possibility of adrenal insufficiency. This is

im-portant, since severe hypotension caused by adrenal in-sufficiency may evoke

a medical emergency. Adrenal insufficiency should always be considered in patients

who are being withdrawn from prolonged glucocorti-coid therapy unless

metyrapone or insulin hypo-glycemia tests are performed to exclude this

possibility.

An additional problem

associated with glucocorti-coid therapy is that certain side effects can be

caused by the diseases for which glucocorticoids are adminis-tered. Thus,

osteoporosis can be a sequela of rheuma-toid arthritis, and the physician is

left to determine whether the untoward effect is iatrogenic or is merely a sign

of the disease being treated. In addition to these problems, the physician must

also be aware of the pa-tient’s natural reluctance to reduce the dose of

steroid because of its salutary effects, both on the inflamma-tory process and

on the psyche. Thus, the problems as-sociated with withdrawal from long-term

steroid ther-apy in rheumatoid arthritis are additional reasons steroid

treatment should be initiated only after rest, physiotherapy, and nonsteroidal

antiinflammatory drugs or after methotrexate, gold, and D-penicillamine have been

used.

Related Topics