Chapter: Essentials of Anatomy and Physiology: The Lymphatic System and Immunity

Adaptive Immunity

ADAPTIVE IMMUNITY

To adapt means to become suitable, and adaptive immunity can become “suitable” for and respond to almost any foreign antigen. Adaptive immunity is spe-cific and is carried out by lymphocytes and macro-phages.

The majority of lymphocytes are the T lympho-cytes and B lymphocytes, or, more simply, T cells and B cells. In the embryo, T cells are produced in the bone marrow and thymus. They must pass through the thymus, where the thymic hormones bring about their maturation. The T cells then migrate to the spleen, lymph nodes, and lymph nodules, where they are found after birth.

Produced in the embryonic bone marrow, B cells migrate directly to the spleen and lymph nodes and nodules. When activated during an immune response, some B cells will divide many times and become plasma cells that produce antibodies to a specific for-eign antigen.

The mechanisms of immunity that involve T cells and B cells are specific, meaning that one foreign anti-gen is the target each time a mechanism is activated. A macrophage has receptor sites for foreign chemicals such as those of bacterial cell walls or flagella, and may phagocytize just about any foreign material it comes across (as will the Langerhans or dendritic cells). T cells and B cells, however, become very specific, as you will see.

The first step in the destruction of a pathogen or foreign cell is the recognition of its antigens as for-eign. Both T cells and B cells are capable of this, but the immune mechanisms are activated especially well when this recognition is accomplished by macro-phages and a specialized group of T lymphocytes called helper T cells (also called CD4 T cells). The foreign antigen is first phagocytized by a macrophage, and parts of it are “presented” on the macrophage’s cell membrane. Also on the macrophage membrane are “self” antigens that are representative of the antigens found on all of the cells of the individual. Therefore, the helper T cell that encounters this macrophage is presented not only with the foreign antigen but also with “self” antigens for comparison. The helper T cell becomes sensitized to and specific for the foreign antigen, the one that does not belong in the body.

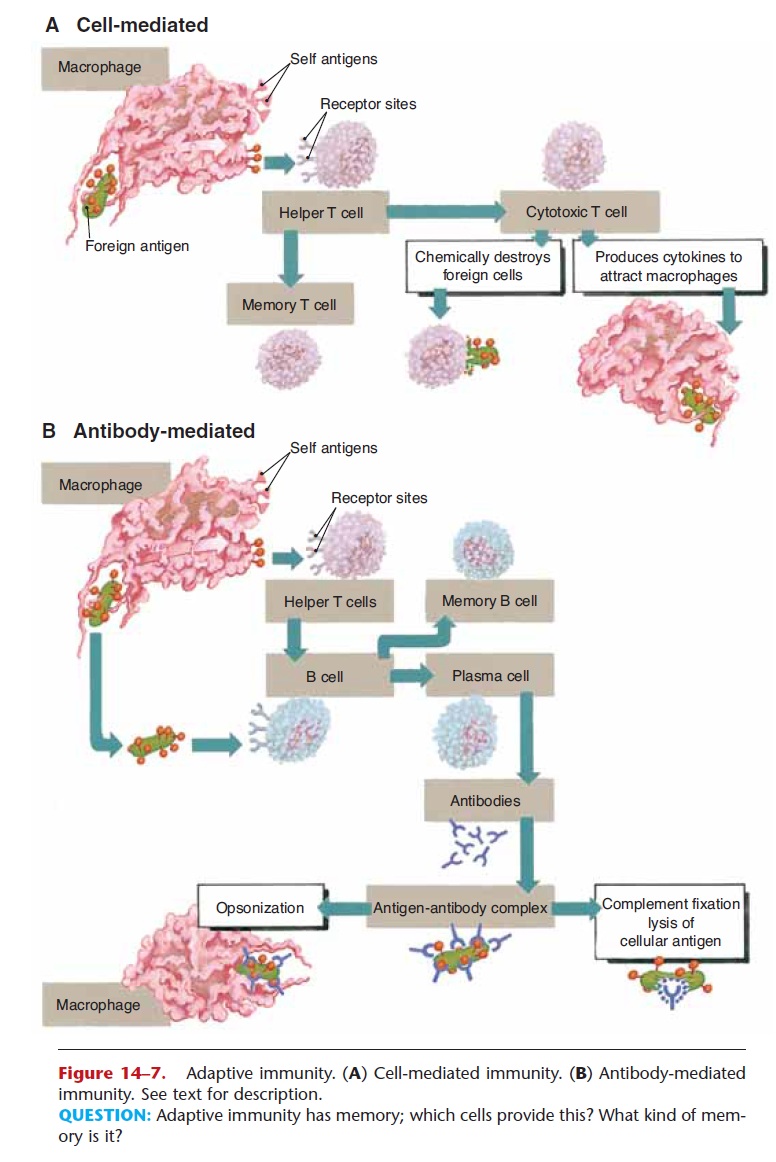

The recognition of an antigen as foreign initiates one or both of the mechanisms of adaptive immunity. These are cell-mediated immunity (sometimes called simply cellular immunity), in which T cells and macrophages participate, and antibody-mediatedimmunity (or humoral immunity), which involves T cells, B cells, and macrophages.

Cell-Mediated Immunity

This mechanism of immunity does not result in the production of antibodies, but it is effective against intracellular pathogens (such as viruses), fungi, malignant cells, and grafts of foreign tissue. As men-tioned earlier, the first step is the recognition of the foreign antigen by macrophages and helper T cells, which become activated and are specific. (You may find it helpful to refer to Fig. 14–7 as you read the fol-lowing.)

Figure 14–7. Adaptive immunity. (A) Cell-mediated immunity. (B) Antibody-mediated immunity. See text for description.

QUESTION: Adaptive immunity has memory; which cells provide this? What kind of mem-ory is it?

These activated T cells, which are antigen specific, divide many times to form memory T cells and cyto-toxic (killer) T cells (also called CD8 T cells). The memory T cells will remember the specific foreign antigen and become active if it enters the body again. Cytotoxic T cells are able to chemically destroy for-eign antigens by disrupting cell membranes. This is how cytotoxic T cells destroy cells infected with viruses and prevent the viruses from reproducing. These T cells also produce cytokines, which are chem-icals that attract macrophages to the area and activate them to phagocytize the foreign antigen and cellular debris.

It was once believed that another subset of T cells served to stop the immune response, but this may not be so. It seems probable that the CD4 and CD8 T cells also produce feedback chemicals to limit the immune response once the foreign antigen has been destroyed. The memory T cells, however, will quickly initiate the cell-mediated immune response should there be a future exposure to the antigen.

Antibody-Mediated Immunity

This mechanism of immunity does involve the pro-duction of antibodies and is also diagrammed in Fig. 14–7. Again, the first step is the recognition of the for-eign antigen, this time by B cells as well as by macrophages and helper T cells. The sensitized helper T cell presents the foreign antigen to B cells, which provides a strong stimulus for the activation of B cells specific for this antigen. The activated B cells begin to divide many times, and two types of cells are formed. Some of the new B cells produced are memory Bcells, which will remember the specific antigen and initiate a rapid response upon a second exposure. Other B cells become plasma cells that produce anti-bodies specific for this one foreign antigen.

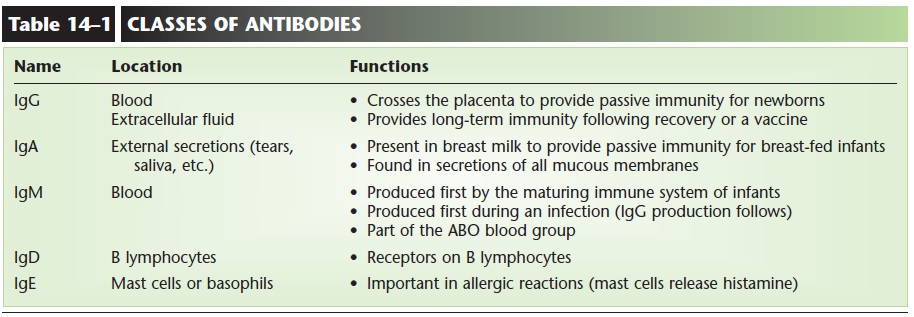

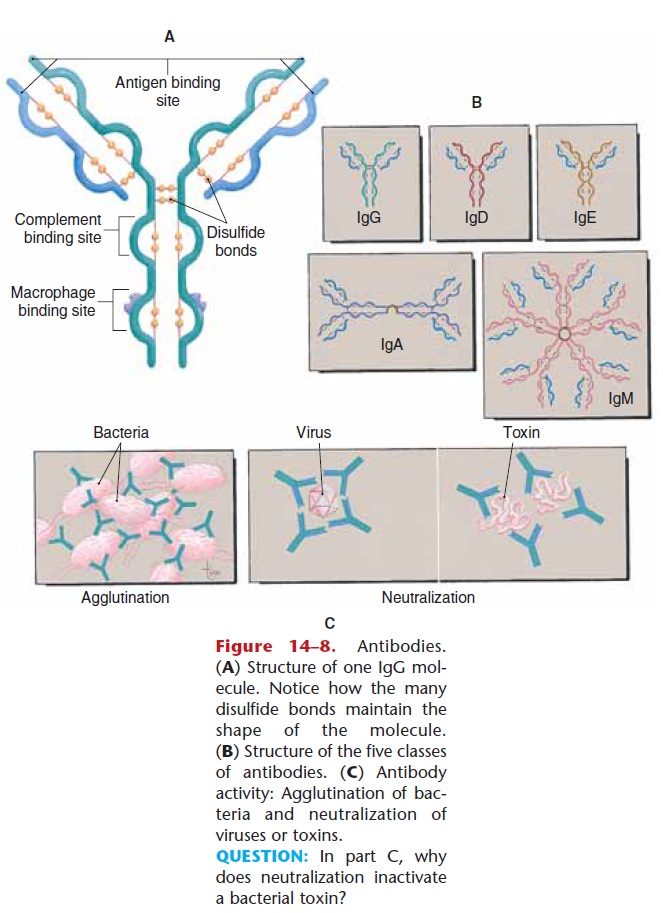

Antibodies, also called immune globulins (Ig) or gamma globulins, are proteins shaped somewhat like the letter Y. Antibodies do not themselves destroy for-eign antigens, but rather become attached to such anti-gens to “label” them for destruction.

Each antibody produced is specific for only one antigen. Because there are so many different pathogens, you might think that the immune system would have to be capa-ble of producing many different antibodies, and in fact this is so. It is estimated that millions of different anti-gen-specific antibodies can be produced, should there be a need for them. The structure of antibodies is shown in Fig. 14–8, and the five classes of antibodies are described in Table 14–1.

The antibodies produced will bond to the antigen, forming an antigen–antibody complex. This complex results in opsonization, which means that the antigen

Figure 14–8. Antibodies. (A) Structure of one IgG mol-ecule. Notice how the many disulfide bonds maintain the shape of the molecule. (B) Structure of the five classes of antibodies. (C) Antibody activity: Agglutination of bac-teria and neutralization of viruses or toxins.

QUESTION: In part C, why does neutralization inactivate a bacterial toxin

Some of the circulating complement proteins are activated, or fixed, by an antigen–antibody complex. Complement fixation may be complete or partial. If the foreign antigen is cellular, the complement pro-teins bond to the antigen–antibody complex, then to one another, forming an enzymatic ring that punches a hole in the cell to bring about the death of the cell. This is complete (or entire) complement fixation and is what happens to bacterial cells (it is also the cause of hemolysis in a transfusion reaction).

If the foreign antigen is not a cell—let’s say it’s a virus for example—partial complement fixation takes place, in which some of the complement proteins bond to the antigen–antibody complex. This is a chemotac-tic factor. Chemotaxis means “chemical movement” and is actually another label that attracts macrophages to engulf and destroy the foreign antigen.

In summary, adaptive immunity is very specific, does create memory, and because it does, often be-comes more efficient with repeated exposures.

Antibody Responses

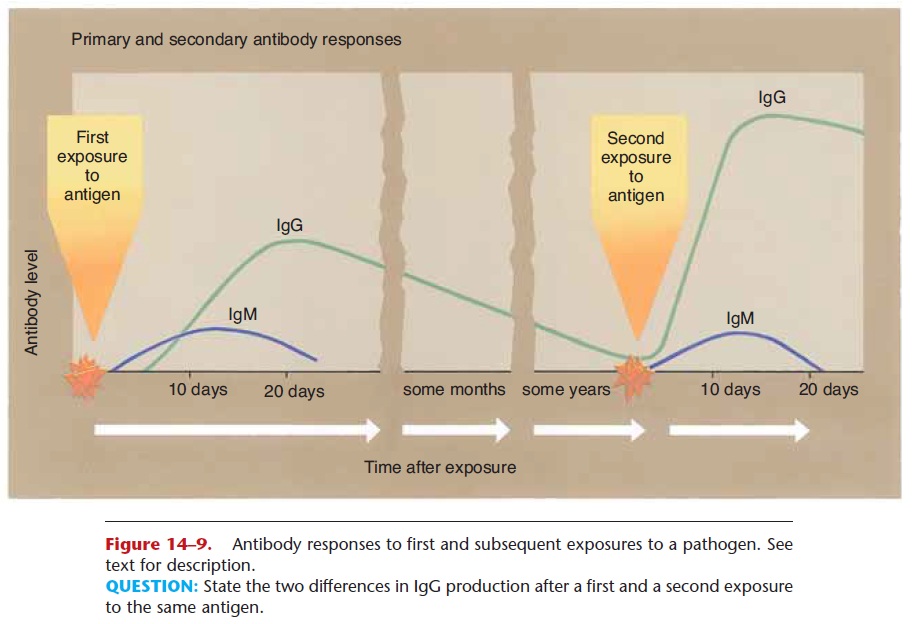

The first exposure to a foreign antigen does stimulate antibody production, but antibodies are produced slowly and in small amounts (see Fig. 14–9). Let us take as a specific example the measles virus. On a per-son’s first exposure to this virus, antibody production is usually too slow to prevent the disease itself, and the person will have clinical measles. Most people who get measles recover, and upon recovery have antibodies and memory cells that are specific for the measles virus.

On a second exposure to this virus, the memory cells initiate rapid production of large amounts of anti-bodies, enough to prevent a second case of measles. This is the reason why we develop immunity to certain diseases, and this is also the basis for the protection given by vaccines.

As mentioned previously, antibodies label patho-gens or other foreign antigens for phagocytosis or complement fixation. More specifically, antibodies cause agglutination or neutralization of pathogens before their eventual destruction. Agglutination means “clumping,” and this is what happens when antibodies bind to bacterial cells. The bacteria that are clumped together by attached antibodies are more eas-ily phagocytized by macrophages (see Fig. 14–8).

The activity of viruses may be neutralized by anti-bodies. A virus must get inside a living cell in order to reproduce itself. However, a virus with antibodies attached to it is unable to enter a cell, cannot repro-duce, and will soon be phagocytized. Bacterial toxins may also be neutralized by attached antibodies. The antibodies change the shape of the toxin, prevent it from exerting its harmful effects, and promote its phagocytosis by macrophages.

Allergies are also the result of antibody activity.

Related Topics