Chapter: Medical Physiology: Heart Muscle; The Heart as a Pump and Function of the Heart Valves

Action Potentials in Cardiac Muscle

Action Potentials in Cardiac Muscle

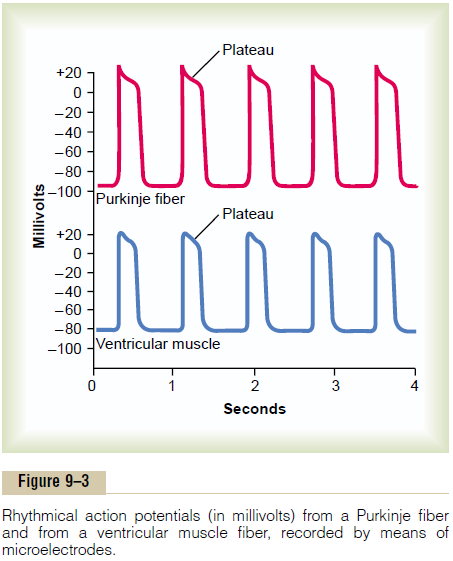

The action potential recorded in a ventricular muscle fiber, shown in Figure 9–3, averages about 105 milli-volts, which means that the intracellular potential rises from a very negative value, about -85 millivolts, between beats to a slightly positive value, about +20 millivolts, during each beat. After the initial spike, the membrane remains depolarized for about 0.2 second, exhibiting a plateau as shown in the figure, followed at the end of the plateau by abrupt repolarization. The presence of this plateau in the action potential causes ventricular contraction to last as much as 15 times as long in cardiac muscle as in skeletal muscle.

What Causes the Long Action Potential and the Plateau? Atthis point, we must ask the questions:Why is the action potential of cardiac muscle so long, and why does it have a plateau, whereas that of skeletal muscle does not?

At least two major differences between the mem-brane properties of cardiac and skeletal muscle account for the prolonged action potential and the plateau in cardiac muscle. First, the action potential ofskeletal muscle is caused almost entirely by suddenopening of large numbers of so-called fast sodiumchannels that allow tremendous numbers of sodiumions to enter the skeletal muscle fiber from the extra-cellular fluid. These channels are called “fast” channels because they remain open for only a few thousandths of a second and then abruptly close. At the end of this closure, repolarization occurs, and the action potential is over within another thousandth of a second or so.

In cardiac muscle, the action potential is caused by opening of two types of channels: (1) the same fastsodium channels as those in skeletal muscle and (2)another entirely different population of slow calciumchannels, which are also called calcium-sodium channels.This second population of channels differsfrom the fast sodium channels in that they are slower to open and, even more important, remain open for several tenths of a second. During this time, a large quantity of both calcium and sodium ions flows through these channels to the interior of the cardiac muscle fiber, and this maintains a prolonged period of depolarization, causing the plateau in the action poten-tial. Further, the calcium ions that enter during this plateau phase activate the muscle contractile process, while the calcium ions that cause skeletal muscle con-traction are derived from the intracellular sarcoplas-mic reticulum.

The second major functional difference between cardiac muscle and skeletal muscle that helps account for both the prolonged action potential and its plateau is this: Immediately after the onset of the action poten-tial, the permeability of the cardiac muscle membrane for potassium ions decreases about fivefold, an effect that does not occur in skeletal muscle. This decreased potassium permeability may result from the excess calcium influx through the calcium channels just noted. Regardless of the cause, the decreased potas-sium permeability greatly decreases the outflux of positively charged potassium ions during the action potential plateau and thereby prevents early return of the action potential voltage to its resting level. When the slow calcium-sodium channels do close at the end of 0.2 to 0.3 second and the influx of calcium and sodium ions ceases, the membrane permeability for potassium ions also increases rapidly; this rapid loss of potassium from the fiber immediately returns the membrane potential to its resting level, thus ending the action potential.

Velocity of Signal Conduction in Cardiac Muscle. The veloci-ty of conduction of the excitatory action potential signal along both atrial and ventricular muscle fibers is about 0.3 to 0.5 m/sec, or about 1/250 the velocity in very large nerve fibers and about 1/10 the velocity in skele-tal muscle fibers. The velocity of conduction in the specialized heart conductive system—in the Purkinjefibers—is as great as 4 m/sec in most parts of thesystem, which allows reasonably rapid conduction of the excitatory signal to the different parts of the heart.

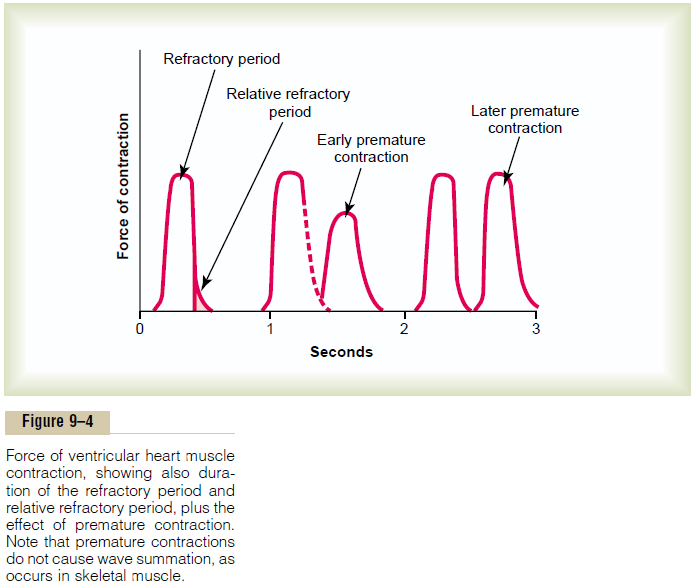

Refractory Period of Cardiac Muscle. Cardiac muscle, likeall excitable tissue, is refractory to restimulation during the action potential. Therefore, the refractory period of the heart is the interval of time, as shown to the left in Figure 9–4, during which a normal cardiac impulse cannot re-excite an already excited area of cardiac muscle. The normal refractory period of the ventricle is 0.25 to 0.30 second, which is about the duration of the prolonged plateau action potential. There is an additional relative refractory period of

about 0.05 second during which the muscle is more dif-ficult than normal to excite but nevertheless can be excited by a very strong excitatory signal, as demon-strated by the early “premature” contraction in the second example of Figure 9–4. The refractory period of atrial muscle is much shorter than that for the ven-tricles (about 0.15 second for the atria compared with 0.25 to 0.30 second for the ventricles).

Excitation-Contraction Coupling—Function of Calcium Ions and the Transverse Tubules

The term “excitation-contraction coupling” refers to the mechanism by which the action potential causes the myofibrils of muscle to contract. Once again, there are differences in this mechanism in cardiac muscle that have important effects on the characteristics of cardiac muscle contraction.

As is true for skeletal muscle, when an action poten-tial passes over the cardiac muscle membrane, the action potential spreads to the interior of the cardiac muscle fiber along the membranes of the transverse(T) tubules. The T tubule action potentials in turn act on the membranes of the longitudinal sarcoplasmic tubules to cause release of calcium ions into the muscle sarcoplasm from the sarcoplasmic reticulum. In another few thousandths of a second, these calcium ions diffuse into the myofibrils and catalyze the chemi-cal reactions that promote sliding of the actin and myosin filaments along one another; this produces the muscle contraction.

Thus far, this mechanism of excitation-contraction coupling is the same as that for skeletal muscle, but there is a second effect that is quite different. In addi-tion to the calcium ions that are released into the sarcoplasm from the cisternae of the sarcoplasmic reticulum, a large quantity of extra calcium ions also diffuses into the sarcoplasm from the T tubules them-selves at the time of the action potential. Indeed, without this extra calcium from the T tubules, the strength of cardiac muscle contraction would be reduced considerably because the sarcoplasmic re-ticulum of cardiac muscle is less well developed than that of skeletal muscle and does not store enough calcium to provide full contraction. Conversely, the T tubules of cardiac muscle have a diameter 5 times as great as that of the skeletal muscle tubules, which means a volume 25 times as great. Also, inside the T tubules is a large quantity of mucopolysaccharides that are electronegatively charged and bind an abundant store of calcium ions, keeping these always available for diffusion to the interior of the cardiac muscle fiber when a T tubule action potential appears.

The strength of contraction of cardiac muscle depends to a great extent on the concentration of calcium ions in the extracellular fluids. The reason for this is that the openings of the T tubules pass directly through the cardiac muscle cell membrane into the extracellular spaces surrounding the cells, allowing the same extracellular fluid that is in the cardiac muscle interstitium to percolate through the T tubules as well. Consequently, the quantity of calcium ions in the T tubule system—that is, the availability of calcium ions to cause cardiac muscle contraction—depends to a great extent on the extracellular fluid calcium ion concentration.

(By way of contrast, the strength of skeletal muscle contraction is hardly affected by moderate changes in extracellular fluid calcium concentration because skeletal muscle contraction is caused almost entirely by calcium ions released from the sarcoplasmic retic-uluminside the skeletal muscle fiber itself.)

At the end of the plateau of the cardiac action potential, the influx of calcium ions to the interior of the muscle fiber is suddenly cut off, and the calcium ions in the sarcoplasm are rapidly pumped back out of the muscle fibers into both the sarcoplasmic reticulum and the T tubule–extracellular fluid space. As a result, the contraction ceases until a new action potential comes along.

Duration of Contraction. Cardiac muscle begins to contracta few milliseconds after the action potential begins and continues to contract until a few milliseconds after the action potential ends. Therefore, the duration of con-traction of cardiac muscle is mainly a function of the duration of the action potential, including the plateau— about 0.2 second in atrial muscle and 0.3 second in ven-tricular muscle.

Related Topics