Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: Clinical Evaluation and Treatment Planning: A Multimodal Approach

Psychiatric Interview

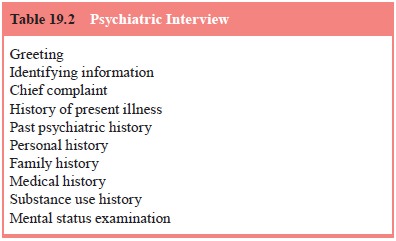

Psychiatric Interview

Despite the advent of brain imaging tests,

standardized diag-nostic criteria and structured rating scales, the psychiatric

inter-view (Table 19.2) remains the cornerstone of clinical evaluation in

psychiatry. Whether it is conducted in a busy psychiatric emer-gency room, an

inpatient ward, or an outpatient office, the psy-chiatric interview is

essential for establishing rapport with the patient, initiating the therapeutic

alliance, eliciting the psychiat-ric history and performing the Mental Status

Examination. When conducted skillfully, the interview may appear to be a

relaxed and casual conversation, but it is actually an extremely precise

diagnostic tool composed of specific elements: the identifying in-formation,

the chief complaint, the history of present illness, the past psychiatric

history, the personal history, the family history, the medical history, the

substance use history and the Mental Status Examination (MSE). The essential

features of the psychi-atric interview are highlighted here.

Before beginning, the psychiatrist should introduce

him-self or herself, explain the purpose of the interview, and try to make the

patient as comfortable as possible. The interview gives the most accurate

information when the psychiatrist and patient speak in a language in which they

are both fluent. When this is not possible, a translator should be used,

preferably one with mental health training or experience. Even then, some of

the sub-tleties of the patient’s communications are lost.

Identifying Information

Most interviewers find it helpful to begin with a

few questions designed to identify the patient in a general way. Asking the

pa-tient’s name, age, address, marital status and occupation provides a quick

general picture and begins the interview with emotion-ally neutral material. If

the interviewer chooses to begin in this way, it is important to complete this

section rapidly and then give the patient a chance to respond to open-ended

questions. This al-lows the interviewer to gain a more accurate sense of the

patient’s spontaneous speech patterns, thought processes and thought con-tent.

If the patient becomes too disorganized in response to this change, the

psychiatrist can revert to more focused questions to structure and organize the

interview. If it is possible, within the context of the interview, other pieces

of identifying information, such as the patient’s ethnic group and religious

affiliation, should be obtained.

Chief Complaint

At the start, the interviewer wants to ascertain

exactly why the pa-tient is seeking psychiatric help at this time. The

interviewer may begin with a fairly general question, such as “What brings you

to treatment at this time?’’ The patient may have a long history of psychiatric

illness, but the chief complaint refers only to the acute problem that

necessitates the current intervention. The in-terviewer should try to help the

patient distinguish the chief com-plaint from any chronic problems, as in the

following example:

Interviewer: Can you

tell me what brings you to see a psychiatrist at this time?

Patient: Well, I

have had schizophrenia for 25 years.

Interviewer: I see.

But my guess is that something happened re-cently that has prompted you to come

in today, rather than several months ago.

Patient: Oh, yes.

Yesterday my wife kicked me out of the house.

I’m homeless.

Here the patient’s chief complaint is homelessness;

the schizophre-nia is part of his psychiatric history. Although a psychotic

patient may offer a chief complaint that seems incoherent or unrealistic, it is

important to collect the chief complaint in the patient’s words and later look

to other sources of information for additional his-tory. Similarly, in response

to the question, “What brings you to seek psychotherapy at this time?’’ a

patient may begin to answer by detailing his or her childhood, but the

interviewer should help the patient to focus on current issues that

precipitated the consul-tation. Some patients may not be able to cite a chief

complaint: “My wife sent me’’ or “There’s no problem. I don’t know why the

police picked me up’’. Even these answers give the interviewer information

about the patient’s current situation, which can be elaborated on by asking the

patient for more details.

When the interview is being conducted for a third

party – for example to determine whether a patient is eligible for dis-ability

– the chief complaint is replaced by the purpose of the interview. The

psychiatrist should review such purpose with the patient and discuss the limits

of confidentiality.

History of Present Illness

Having obtained the chief complaint, the

interviewer should clarify the nature of the present illness. By definition,

the present illness begins with the onset of signs and symptoms that

char-acterize the current episode of illness. For example, the present illness

of a manic patient with chronic bipolar disorder who was asymptomatic for the

past 3 years would begin with the onset of the current episode of mania. The

interviewer should determine the duration of the present illness, as well as precipitating

fac-tors such as psychosocial stressors, substance use, discontinuing

medication and medical illnesses. The patient should be allowed to tell the

story, and the clinician should follow-up with specific diagnostic questions.

For example, a patient who tells a story of 6 months of sadness after the death

of a relative should then be asked about vegetative symptoms of depression,

suicidal ideation and guilty rumination.

Past Psychiatric History

The interviewer should ask for information regarding any previ-ous episodes of psychiatric illness or treatment, including hospi-talization, medications, outpatient therapy, substance use treat-ment, self-help groups and consultation with culture-specific healers such as shamans. The duration and effectiveness of treat-ment should be ascertained, as well as the patient’s general expe-rience of her or his psychiatric treatment to date.

Personal History

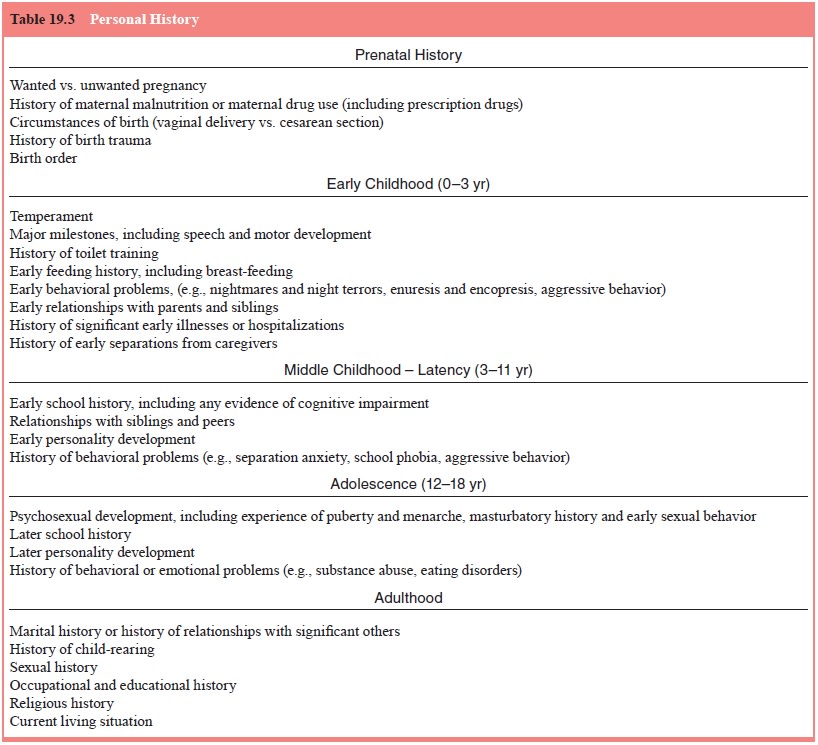

No interview is complete without some understanding

of the pa-tient’s background and life circumstances (Table 19.3). Within the

constraints of the interviewer’s time and the patient’s toler-ance for further

questioning, the clinician should inquire about the patient’s upbringing,

educational and vocational history, in-terpersonal relations and current social

situation. It is important to inquire about the patient’s sexual history and to

ask about risk factors for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, such

as a history of multiple partners, unprotected vaginal and anal in-tercourse,

and intravenous drug use. This information is relevant not only for the

assessment and diagnosis of the present illness but also for treatment

planning.

Family History

The interviewer should ask the patient specifically

about any relatives with a history of psychiatric illness or treatment,

sui-cide, or substance use. This information may be of diagnostic importance.

For example, a patient who presents with a firstepisode of acute psychosis may

have any one of a number of dis-orders, but a family history of affective

disorders may lead the interviewer to suspect a diagnosis of bipolar disorder

or major depression with psychotic features rather than schizophrenia. This

information is also important for treatment planning, par-ticularly if the

patient’s primary caregivers are also psychiatri-cally ill or also abuse

substances.

Medical History

A careful review of a patient’s medical history is

an important part of the psychiatric interview because medical conditions can

dramatically affect psychiatric status. Many medical disorders such as

endocrinological conditions (thyroid disease, pheochro-mocytomas, pituitary

adenomas), neurological disorders (Par-kinson’s disease, central nervous system

neoplasms, Wilson’s disease, stroke syndromes, head trauma) and infectious

diseases (HIV infection, meningitis, sepsis) can have manifestations that

include psychiatric symptoms. When such a disorder is suspected, rigorous

inquiry is essential. A review of all of the patient’s medications, including

over-the-counter preparations and alternative remedies, is important because

many of these substances can produce or exacerbate psychiatric symptoms. For

example, propranolol taken for hypertension may produce symptoms of depression,

and scopolamine taken for mo-tion sickness may induce delirium. Finally, the

toll of chronic, de-bilitating medical conditions or the acute onset of a

catastrophic physical illness may be accompanied by secondary psychiatric

symptoms that can be fully understood only in the context of the patient’s medical

condition.

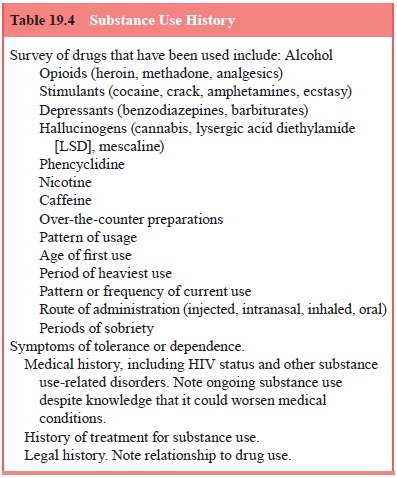

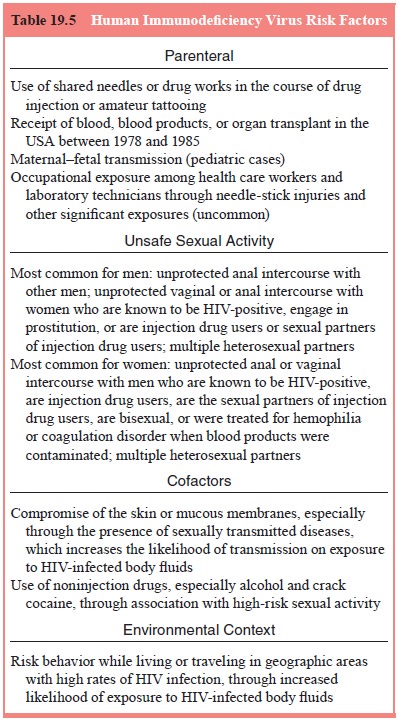

Substance Use History

The interviewer should inquire about which

substances are used, under what circumstances, and the quantity, variety, and

duration of use (Table 19.4). A question such as “Do you drink alcohol?’’ is

likely to be answered with a quick “No’’. A better question, such as “How much

alcohol do you drink?’’ communicates to the pa-tient that the clinician is not

making a value judgment and is more likely to elicit an accurate answer. The

interviewer must be sure to ask about past and current drug injection,

including the sharing of injection equipment, to assess for HIV risk factors

(Table 19.5).

Mental Status Examination

The MSE is a structured way to assess a patient’s

mental state at a given time. Unlike the parts of the interview that focus on

the history, the MSE provides a descriptive snapshot of the patient at the

interview. Much of the information needed for the evaluation of appearance,

behavior and speech is gathered without specific questioning during the course

of the interview. However, the interviewer generally wants to ask specific

questions to assess the patient’s mood, thought process and content and

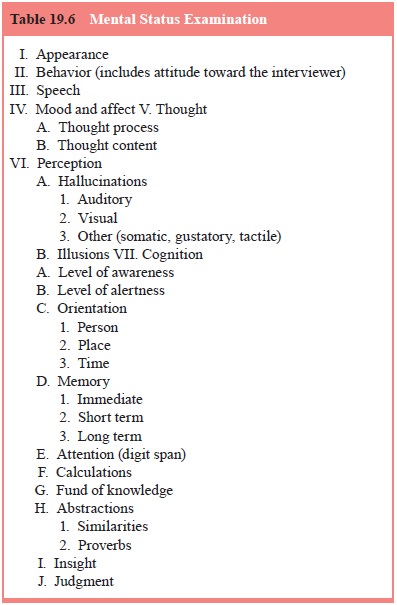

cognitive functioning. Bearing in mind the outline of the MSE (Table 19.6)

ensures that the interview is comprehensive. The components of the MSE are

described in the following paragraphs.

Appearance

The interviewer should note the patient’s general

appearance, in-cluding grooming, level of hygiene and attire.

Behavior

This includes patient’s level of cooperativeness

with the inter-view, motor excitement or retardation, abnormal movements (e.g.,

tardive dyskinesia, tremors), and maintenance of eye con-tact with the

interviewer.

Speech

The psychiatrist should carefully assess the patient’s speech for rate, fluency, clarity and softness or loudness. The interviewer may want to question the patient directly about his or her speech. For example, the psychiatrist can gain valuable diagnostic informa-tion by asking a patient with pressured speech if she or he is able to modulate the rate of the speech or by asking whether a dysarthric patient is aware of not speaking clearly. A bipolar patient who is in the midst of a manic episode is not able to slow down her or his speech; a fast-talking anxious person is able to do so. Similarly a patient whose dysarthria is secondary to ill-fitting dentures is aware of this problem whereas an intoxicated person is not. It is helpful to clarify whether patients with a speech abnormality feel that this is their normal speech pattern or a new problem.

Mood and Affect

The interviewer should be aware of the patient’s

mood and affect. This may be evident from the way in which the patient answers

other questions and tells the history, but specific questions are often

indicated. The patient’s mood is a pervasive affective state, and it is often

helpful simply to ask, “What has your mood been like lately?’’ or “How would

you describe your mood?’’ In con-trast, affect is the way in which one

modulates and conveys one’s feeling state from moment to moment. The clinician

judges the congruity between the material the patient is presenting and the

accompanying affect, that is, sadness when discussing the death of a loved one

or happiness when describing a child’s accom-plishments. This reveals whether

the affect is labile (shifts too rapidly) and whether it is appropriate to the

content of the mate-rial.

Thought

The clinician should assess the patient’s thought

process and con-tent. Thought process is the form of the patient’s thoughts –

are they organized and goal directed or are they tangential, circum-stantial,

or loosely associated? If the patient’s thought processes are difficult to

understand, the clinician can indicate his or her difficulty in fol-lowing what

is being said and then assess the patient’s response to this intervention. Some

patients – such as patients with stroke who have nonfluent aphasias – may

appear to have disorganized speech but are aware that they are not making

sense, whereas those with fluent aphasias, psychosis and delirium are not

nec-essarily aware of their impairment. The psychiatrist should ask

specifically about the patient’s thought content, including delu-sions

(grandiose, persecutory, somatic), hallucinations (auditory, visual, tactile

and olfactory), obsessions, phobias, and suicidal and homicidal ideation.

Although these questions should be asked with tact and empathy, they should

always be asked. Pa-tients are generally relieved that the interviewer has

broached the subject of suicide, and simply asking the question does not give

patients ideas they have not had before.

Cognition

Every psychiatric interview should include some

assessment of the patient’s cognitive functioning. This includes the patient’s

level of awareness, alertness and orienta-tion (to person, place and time). If

there is a question about the patient’s memory, formal memory testing may be

done to assess short-term, intermediate and long-term memory. A patient who can

answer questions for 30 minutes is clearly attentive, but any doubts about the

patient’s attentiveness should prompt a formal assessment, for example, asking

the patient to recite a series of digits forward and backward. Before assessing

the patient’s cal-culations and fund of knowledge, it is important to ascertain

the patient’s level of education. Formal assessment of the patient’s ability to

abstract may be unnecessary for a patient who has used abstract constructions

throughout the interview, but the inter-viewer may want to ask formally for interpretations

of similes and proverbs. It is often helpful to begin with simple

constructions, for example, asking the patient the meaning of such phrases as

“He has a warm heart’’ or “Save your money for a rainy day’’. Patients whose

native language is not English may have difficulty in this area that does not

reflect a lack of ability to abstract.

The interviewer should gain a full understanding of

the pa-tient’s insight into the illness by asking why, in the patient’s

opin-ion, he/she is currently in need of psychiatric care and what has caused

problems. Finally, the interviewer should learn about the patient’s judgment.

This is best assessed in terms of the circum-stances of the patient’s life, for

example, asking a mother how she would deal with a situation in which she had

to leave her children to go to the store or asking a chronically ill person

what he does when he sees that he is running out of medicine.

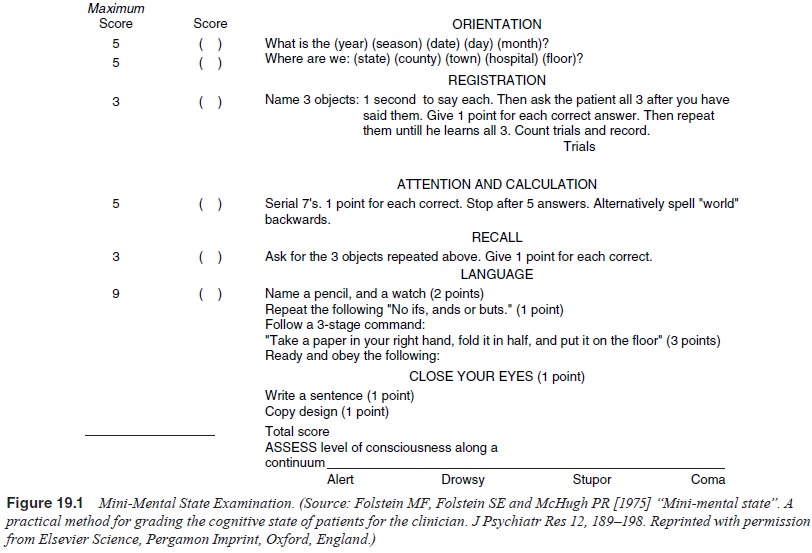

The interviewer may want to use the Mini-Mental

State Examination (Mini-MSE) to quantify the degree of cognitive im-pairment of

a patient with obvious cognitive abnormalities. This can be useful as an

initial diagnostic tool, as well as a means of assessing changes in cognitive

function over time. The Mini-MSE is outlined in Figure 19.1.

Related Topics