Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Management of Patients With Neurologic Trauma

Nursing Process: The Patient With Acute Spinal Cord Injury

NURSING PROCESS: THE PATIENT WITH

ACUTE SPINAL CORD INJURY

Assessment

The breathing pattern is observed, the strength of the

cough is as-sessed, and the lungs are auscultated, because paralysis of

ab-dominal and respiratory muscles diminishes coughing and makes it difficult

to clear bronchial and pharyngeal secretions. Reduced excursion of the chest

also results.

The patient is monitored

closely for any changes in motor or sensory function and for symptoms of

progressive neurologic dam-age. It may be impossible in the early stages of SCI

to determine whether the cord has been severed, because signs and symptoms of

cord edema are indistinguishable from those of cord transection. Edema of the

spinal cord may occur with any severe cord injury and may further compromise

spinal cord function.

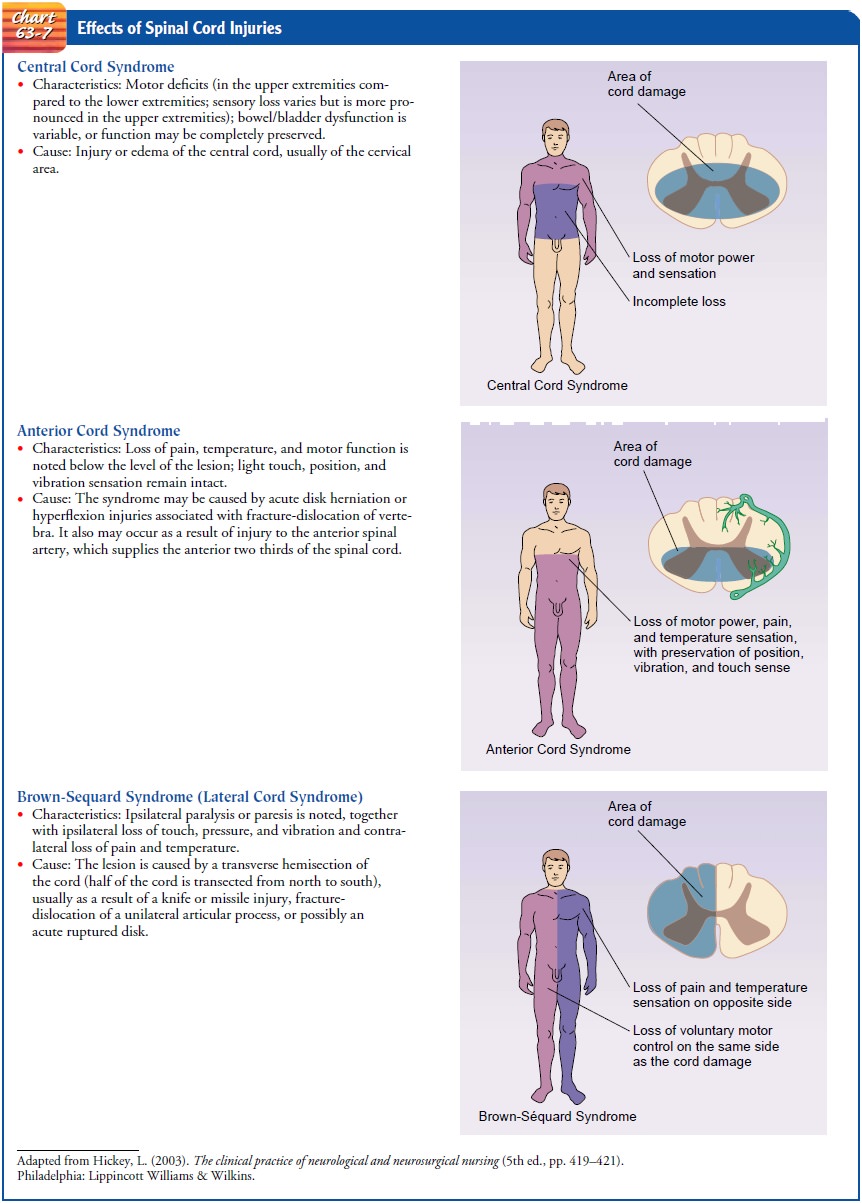

Motor and sensory

functions are assessed through careful neu-rologic examination. These findings

are recorded most often on a flow sheet so that changes in the baseline

neurologic status can be closely monitored accurately. The American Spinal

Injury Associ-ation (ASIA) classification is commonly used to describe level of

function for SCI patients. Chart 63-7 also gives an example of nursing

assessment of spinal cord function.

·

Motor

ability is tested by asking the patient to spread the fingers, squeeze the

examiner’s hand, and move the toes or turn the feet.

·

Sensation is evaluated by

gently pinching the skin or touch-ing it lightly with a small object such as a

tongue blade, starting at shoulder level and working down both sides of the

extremities. The patient should have both eyes closed so that the examination

reveals true findings, not what the pa-tient hopes to feel. The patient is

asked where the sensation is felt.

·

Any decrease in neurologic

function is reported immediately.

The patient is also assessed for spinal shock, a complete

loss of all reflex, motor, sensory, and autonomic activity below the level of

the lesion that causes bladder paralysis and distention. The lower abdomen is

palpated for signs of urinary retention and overdistention of the bladder.

Further assessment is made for gastric dilation and ileus due to an atonic

bowel, a result of auto-nomic disruption.

Temperature is monitored because the patient may have

peri-ods of hyperthermia as a result of alteration in temperature control due

to autonomic disruption.

Diagnosis

NURSING DIAGNOSES

Based on the assessment data, the patient’s major nursing

diag-noses may include the following:

·

Ineffective breathing patterns

related to weakness or paral-ysis of abdominal and intercostal muscles and

inability to clear secretions

·

Ineffective airway clearance

related to weakness of inter-costal muscles

·

Impaired physical mobility

related to motor and sensory impairment

·

Disturbed sensory perception

related to motor and sensory impairment

·

Risk for impaired skin

integrity related to immobility and sensory loss

·

Urinary retention related to

inability to void spontaneously

·

Constipation related to

presence of atonic bowel as a result of autonomic disruption

·

Acute pain and discomfort

related to treatment and pro-longed immobility

COLLABORATIVE PROBLEMS/ POTENTIAL COMPLICATIONS

Based on the assessment data, potential complications

that may develop include:

·

DVT

·

Orthostatic hypotension

·

Autonomic dysreflexia

Planning and Goals

The goals for the patient may include improved breathing

pat-tern and airway clearance, improved mobility, improved sensory and

perceptual awareness, maintenance of skin integrity, relief of urinary

retention, improved bowel function, promotion of com-fort, and absence of

complications.

Nursing Interventions

PROMOTING ADEQUATE BREATHING AND AIRWAY CLEARANCE

Possible impending respiratory failure is detected by

observing the patient, measuring vital capacity, monitoring oxygen satura-tion

through pulse oximetry, and monitoring arterial blood gas values. Early and

vigorous attention to clearing bronchial and pharyngeal secretions can prevent

retention of secretions and at-electasis. Suctioning may be indicated, but

caution must be used during suctioning because this procedure can stimulate the

vagus nerve, producing bradycardia, which can result in cardiac arrest.

If the patient cannot cough effectively because of

decreased in-spiratory volume and inability to generate sufficient expiratory

pressure, chest physical therapy and assisted coughing may be in-dicated.

Specific breathing exercises are supervised by the nurse to increase the

strength and endurance of the inspiratory muscles, particularly the diaphragm.

Assisted coughing promotes clearing of secretions from the upper respiratory

tract and is similar to using abdominal thrusts to clear an airway. It is

important to ensure proper humidification and hydration to pre-vent secretions

from becoming thick and difficult to remove even with coughing. The patient is

assessed for signs of respiratory in-fection (cough, fever, dyspnea). Smoking

is discouraged because it increases bronchial and pulmonary secretions and

impairs ciliary action.

Ascending edema of the spinal cord in the acute phase may

cause respiratory difficulty that requires immediate intervention. Therefore,

the patient’s respiratory status must be monitored frequently.

IMPROVING MOBILITY

Proper body alignment is maintained at all times. The

patient is repositioned frequently and is assisted out of bed as soon as the

spinal column is stabilized. The feet are prone to footdrop; therefore, various

types of splints are used to prevent footdrop. When used, the splints are

removed and reapplied every 2 hours. Trochanter rolls, applied from the crest

of the ilium to the midthigh of both legs, help prevent external rotation of

the hip joints.

Patients with lesions above the midthoracic level have

loss of sympathetic control of peripheral vasoconstrictor activity, lead-ing to

hypotension. These patients may tolerate changes in posi-tion poorly and

require monitoring of blood pressure when positions are changed. Usually the

patient is turned every 2 hours. If not on a rotating bed, the patient should

not be turned unless the spine is stable and the physician has indicated that

it is safe to do so.

Contractures develop rapidly with immobility and muscle

paralysis. A joint that is immobilized too long becomes fixed as a result of

contractures of the tendon and joint capsule. Atrophy of the extremities

results from disuse. Contractures and other com-plications may be prevented by

range-of-motion exercises that help preserve joint motion and stimulate

circulation. Passive range-of-motion exercises should be implemented as soon as

possible after injury. Toes, metatarsals, ankles, knees, and hips should be put

through a full range of motion at least four, and ideally five, times daily.

For most patients with a cervical fracture without

neurologic deficit, reduction in traction followed by rigid immobilization for

about 6 to 8 weeks restores skeletal integrity. These patients are allowed to

move gradually to an erect position. A four-poster neck brace or molded collar

is applied when the patient is mobi-lized after traction is removed (see Fig.

63-8).

PROMOTING ADAPTATION TO SENSORY AND PERCEPTUAL ALTERATIONS

The nurse assists the patient to compensate for sensory

and per-ceptual alterations that occur with SCI. The intact senses above the

level of the injury are stimulated through touch, aromas, flavorful food and

beverages, conversation, and music. Additional strategies include the

following:

·

Providing prism glasses to

enable the patient to see from the supine position

·

Encouraging use of hearing

aids, if indicated, to enable the patient to hear conversations and

environmental sounds

·

Providing emotional support to

the patient

·

Teaching the patient

strategies to compensate for or cope with these deficits

MAINTAINING SKIN INTEGRITY

Because the patient with

SCI is immobilized and has loss of sen-sation below the level of the lesion,

there is an ever-present, life-threatening risk of pressure ulcers. In areas of

local tissue ischemia, where there is continuous pressure and where the

peripheral cir-culation is inadequate as a result of the spinal shock and

recum-bent position, pressure ulcers have developed within 6 hours. Prolonged

immobilization of the patient on a transfer board in-creases the risk of

pressure ulcers. The most common sites are over the ischial tuberosity, the

greater trochanter, and the sacrum. In addition, patients who wear cervical

collars for prolonged pe-riods may develop breakdown from the pressure of the

collar under the chin, on the shoulders, and at the occiput.

The patient’s position

is changed at least every 2 hours. Turn-ing not only assists in the prevention

of pressure ulcers but also pre-vents the pooling of blood and tissue fluid in

the dependent areas.

Careful inspection of

the skin is made each time the patient is turned. The skin over the pressure

points is assessed for redness or breaks; the perineum is checked for soilage

and the catheter is observed for adequate drainage. The patient’s general body

align-ment and comfort are assessed. Special attention should be given to

pressure areas in contact with the transfer board.

The patient’s skin

should be kept clean by washing with a mild soap, rinsed well, and blotted dry.

Pressure-sensitive areas should be kept well lubricated and soft with bland

cream or lotion. The patient is informed about the danger of pressure ulcers to

en-courage understanding of the reason for preventive measures.

MAINTAINING URINARY ELIMINATION

Immediately after SCI, the urinary bladder becomes atonic

and cannot contract by reflex activity. Urinary retention is the imme-diate

result. Because the patient has no sensation of bladder dis-tention,

overstretching of the bladder and detrusor muscle may occur, delaying the

return of bladder function.

Intermittent

catheterization is carried out to avoid over-distention of the bladder and UTI.

If this is not feasible, an in-dwelling catheter is inserted temporarily. At an

early stage, family members are shown how to carry out intermittent

catheterization and are encouraged to participate in this facet of care,

because they will be involved in long-term follow-up and must be able to

recognize complications so that treatment can be instituted.

The patient is taught to

record fluid intake, voiding pattern, amounts of residual urine after

catheterization, characteristics of urine, and any unusual sensations that may

occur.

IMPROVING BOWEL FUNCTION

Immediately after SCI, a paralytic ileus usually develops

due to neurogenic paralysis of the bowel; therefore, a nasogastric tube is

often required to relieve distention and prevent aspiration.

Bowel activity usually returns within the first week. As

soon as bowel sounds are heard on auscultation, the patient is given a

high-calorie, high-protein, high-fiber diet, with the amount of food gradually

increased. The nurse administers prescribed stool softeners to counteract the

effects of immobility and pain med-ications. A bowel program is instituted as

early as possible.

PROVIDING COMFORT MEASURES

After cervical injury, if pins, tongs, or calipers are in

place, the skull is assessed for signs of infection, including drainage. The

back of the head is checked periodically for signs of pressure, with care taken

not to move the neck. The hair around the tongs usu-ally is shaved to

facilitate inspection. Probing under encrusted areas is avoided.

The Patient in Halo Traction

Patients who have been placed in a halo device after

cervical sta-bilization may have a slight headache or discomfort around the skull

pins for several days after the pins are inserted. The patient initially may be

bothered by the rather startling appearance of this apparatus but usually

readily adapts to it because the device pro-vides comfort for the unstable

neck. The patient may complain of being caged in and of noise created by any

object coming in contact with the steel frame, but he or she can be reassured

that adaptation to such annoyances will occur.

The areas around the pin sites are cleansed daily and

observed for redness, drainage, and pain. The pins are observed for loos-ening,

which may contribute to infection. If one of the pins be-comes detached, the

head is stabilized in a neutral position by one person while another notifies

the neurosurgeon. A torque screw-driver should be readily available should the

screws on the frame need tightening.

The skin under the halo

vest is inspected for excessive perspi-ration, redness, and skin blistering,

especially on the bony promi-nences. The vest is opened at the sides to allow

the torso to be washed. The liner of the vest should not become wet, because

dampness causes skin excoriation. Powder is not used inside the vest, because

it may contribute to the development of pressure ul-cers. The liner should be

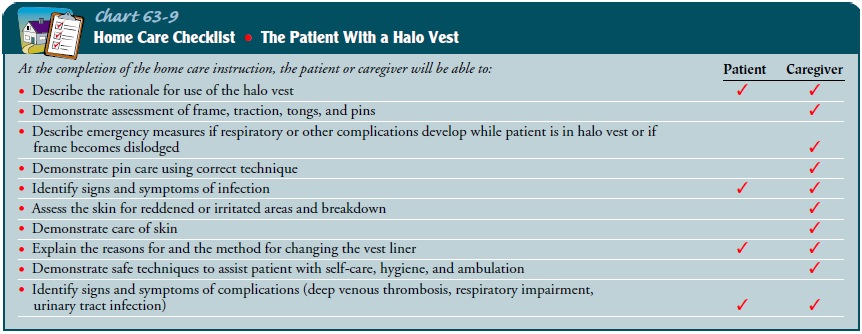

changed periodically to promote hygiene and good skin care. If the patient is

to be discharged with the vest, detailed instructions must be given to the

family and time allowed for them to return demonstrate the necessary skills

(Chart 63-9).

MONITORING AND MANAGING POTENTIAL COMPLICATIONS

Thrombophlebitis

Thrombophlebitis is a

relatively common complication in patients after SCI. DVT occurs in a high

percentage of SCI patients; thus, they are at risk for PE. The patient must be

assessed for symptoms of thrombophlebitis and PE: chest pain, shortness of

breath, and changes in arterial blood gas values must be reported promptly to

the physician. The circumferences of the thighs and calves are measured and

recorded daily; further diagnostic studies will be performed if a significant increase

is noted. Patients remain at high risk for thrombophlebitis for several months

after the ini-tial injury. Patients with paraplegia or quadriplegia are at

in-creased risk for the rest of their lives. Immobilization and the associated

venous stasis, as well as varying degrees of autonomic disruption, contribute

to the high risk and susceptibility for DVT (Zafonte et al., 1999).

Anticoagulation is

initiated once head and other systemic in-juries have been ruled out. Low-dose

fractionated or unfraction-ated heparin may be followed by long-term oral

anticoagulation (ie, warfarin) or subcutaneous fractionated heparin injections.

Additional measures such as range-of-motion exercises, thigh-high elastic

compression stockings, and adequate hydration are important preventive

measures. Pneumatic compression devices may also be used to reduce venous

pooling and promote venous return. It is also important to avoid external

pressure on the lower extremities that may result from flexion of the knees

while the patient is in bed.

Orthostatic Hypotension

For the first 2 weeks

after SCI, the blood pressure tends to be un-stable and quite low. There is a

gradual return to preinjury levels, but periodic episodes of severe orthostatic

hypotension frequently interfere with efforts to mobilize the patient.

Interruption in the reflex arcs that normally produce vasoconstriction in the

upright position, coupled with vasodilation and pooling in abdominal and lower

extremity vessels, can result in blood pressure readings of 40 mm Hg systolic

and 0 mm Hg diastolic. Orthostatic hypo-tension is a particularly common

problem for patients with lesions above T7. In some quadriplegic patients, even

slight elevations of the head can result in dramatic changes in blood pressure.

A number of techniques

can be used to reduce the frequency of hypotensive episodes. Close monitoring

of vital signs before and during position changes is essential. Vasopressor

medication can be used to treat the profound vasodilation. Thigh-high elastic

compression stockings should be applied to improve venous re-turn from the

lower extremities. Abdominal binders may also be used to encourage venous

return and provide diaphragmatic sup-port when upright. Activity should be

planned in advance and adequate time given for a slow progression of position

changes from recumbent to sitting and upright. Tilt tables frequently are

helpful in assisting patients to make this transition.

Autonomic Dysreflexia

Autonomic dysreflexia (autonomic hyperreflexia) is an acuteemergency that occurs as a result of exaggerated autonomic re-sponses to stimuli that are harmless in normal people. It occurs only after spinal shock has resolved. This syndrome is characterized by a severe, pounding headache with paroxysmal hypertension, profuse diaphoresis (most often of the forehead), nausea, nasal congestion, and bradycardia. It occurs among patients with cord lesions above T6 (the sympathetic visceral outflow level) after spinal shock has subsided. The sudden rise in blood pressure may cause a rupture of one or more cerebral blood vessels or lead to increased ICP. A number of stimuli may trigger this reflex: distended bladder (the most common cause); distention or con-traction of the visceral organs, especially the bowel (from consti-pation, impaction); or stimulation of the skin (tactile, pain, thermal stimuli, pressure ulcer). Because this is an emergency situation, the objective is to remove the triggering stimulus and to avoid the possibly serious complications.

The following measures are carried out:

·

The patient is placed

immediately in a sitting position to lower blood pressure.

·

Rapid assessment to identify

and alleviate the cause is im-perative.

·

The bladder is emptied

immediately via a urinary catheter. If an indwelling catheter is not patent, it

is irrigated or re-placed with another catheter.

·

The rectum is examined for a

fecal mass. If one is present, a topical anesthetic is inserted 10 to 15

minutes before the mass is removed, because visceral distention or contraction

can cause autonomic dysreflexia.

·

The skin is examined for any

areas of pressure, irritation, or broken skin.

·

Any other stimulus that can be

the triggering event, such as an object on the skin or a draft of cold air,

must be removed.

·

If these measures do not

relieve the hypertension and ex-cruciating headache, a ganglionic blocking

agent (hydralazine hydrochloride [Apresoline]) is prescribed and given slowly

intravenously.

·

The medical record or chart

should be labeled with a clearly visible note about the risk for autonomic

dysreflexia.

·

The patient is instructed

about prevention and manage-ment measures.

·

Any patient with a lesion

above the T6 segment is informed that such an episode is possible and may even

occur many years after the initial injury.

The rehabilitation of the patient with a SCI (ie, the

quadri-plegic or paraplegic patient) is discussed below.

PROMOTING HOME AND COMMUNITY-BASED CARE

Teaching Patients Self-Care

In most cases, SCI patients need long-term

rehabilitation. The process begins during hospitalization as acute symptoms

begin to subside or come under better control and the overall deficits and

long-term effects of the injury become clear. The goals begin to shift from

merely surviving the injury to learning strategies nec-essary to cope with the

alterations that injury imposes on activi-ties of daily living. The emphasis

shifts from ensuring that the patient is stable and free of complications to

specific assessment and planning designed to meet the patient’s rehabilitation

needs. Patient teaching may initially focus on the injury and its effects on

mobility, dressing, and bowel, bladder, and sexual function. As the patient and

family acknowledge the consequences of the injury, the focus of teaching may

broaden to address issues nec-essary to carry out the tasks of daily living.

Teaching begins in the acute phase and continues throughout rehabilitation and

through-out the patient’s life as changes occur, the patient ages, and problems

arise.

Caring for the SCI patient at home may at first seem a

daunt-ing task to the family. They will require dedicated nursing sup-port to

gradually assume full care of the patient (Craig et al., 1999).

Although maintaining function and preventing

complications will remain important, goals regarding self-care and preparation

for discharge will assist in a smooth transition to rehabilitation and

eventually to the community.

Continuing Care

The ultimate goal of the

rehabilitation process is independence. The nurse becomes a support to both the

patient and the family,assisting them to assume responsibility for increasing

aspects of patient care and management. Care for the SCI patient involves

members of all the health care disciplines; these may include nurs-ing,

medicine, rehabilitation, respiratory therapy, physical and occupational

therapy, case management, social services, and so forth. The nurse often serves

as coordinator of the management team and as a liaison with rehabilitation

centers and home care agencies. The patient and family often require assistance

in deal-ing with the psychological impact of the injury and its conse-quences;

referral to a psychiatric clinical nurse specialist or other mental health care

professional often is helpful.

The nurse should reassure female SCI patients that

pregnancy is not contraindicated, but pregnant women with acute or chronic SCI

pose unique management challenges. The normal physiologic changes of pregnancy

may predispose women with SCI to many potentially life-threatening

complications, includ-ing autonomic dysreflexia, pyelonephritis, respiratory

insuffi-ciency, thrombophlebitis, PE, and unattended delivery (Atterbury &

Groome, 1998).

As more patients survive

acute SCI, they will face the changes associated with aging with a disability.

Thus, teaching in the home and community focuses on health promotion and

ad-dresses the need to minimize risk factors (eg, smoking, alcohol and drug

abuse, obesity). Home care nurses and others who have contact with patients

with SCI are in a position to teach patients about healthy lifestyles, remind

them of the need for health screenings, and make referrals as appropriate.

Assisting patients to identify accessible health care providers and imaging

centers may increase the likelihood that they will participate in health

screening (eg, gynecologic examinations, mammograms, etc.).

Evaluation

EXPECTED PATIENT OUTCOMES

Expected patient outcomes may include:

1) Demonstrates

improvement in gas exchange and clearance of secretions, as evidenced by normal

breath sounds on auscultation

a) Breathes

easily without shortness of breath

b) Performs

hourly deep-breathing exercises, coughs effec-tively, and clears pulmonary

secretions

c) Is

free of respiratory infection (ie, has normal tempera-ture, respiratory rate,

and pulse, normal breath sounds, absence of purulent sputum)

2) Moves

within limits of the dysfunction and demonstrates completion of exercises

within functional limitations

3) Demonstrates

adaptation to sensory and perceptual alter-ations

a) Uses

assistive devices (eg, prism glasses, hearing aids, computers) as indicated

b) Describes

sensory and perceptual alterations as a conse-quence of injury

4) Demonstrates

optimal skin integrity

a) Exhibits

normal skin turgor; skin is free of reddened areas or breaks

b) Participates

in skin care and monitoring procedures within functional limitations

5) Regains

urinary bladder function

a) Exhibits

no signs of UTI (ie, has normal temperature; voids clear, dilute urine)

b) Has

adequate fluid intake

c) Participates

in bladder training program within func-tional limitations

6) Regains

bowel function

a) Reports

regular pattern of bowel movement

b) Consumes

adequate dietary fiber and oral fluids

c) Participates

in bowel training program within func-tional limitations

7) Reports

absence of pain and discomfort

8) Is

free of complications

a) Demonstrates

no signs of thrombophlebitis, DVT, or PE

b) Exhibits

no manifestations of pulmonary embolism (eg, no chest pain or shortness of

breath; arterial blood gas values are normal)

c) Maintains

blood pressure within normal limits

d) Has

no lightheadedness with position changes

e) Exhibits

no manifestations of autonomic dysreflexia (ie, no headache, diaphoresis, nasal

congestion, brady-cardia, or diaphoresis)

Management of the Quadriplegic or Paraplegic Patient

Quadriplegia refers to the loss of movement and sensation

in all four extremities and the trunk, associated with injury to the cer-vical

spinal cord. Paraplegia refers to loss of motion and sensation in the lower

extremities and all or part of the trunk as a result of damage to the thoracic

or lumbar spinal cord or to the sacral root. Both conditions most frequently

follow trauma such as falls, in-juries, and gunshot wounds, but they may also

be the result of spinal cord lesions (intervertebral disk, tumor, vascular

lesions), multiple sclerosis, infections and abscesses of the spinal cord, and

congenital disorders.

The patient faces a

lifetime of great disability, requiring on-going follow-up and care and the

expertise of a number of health professionals, including physicians

(specifically a physiatrist), re-habilitation nurses, occupational therapist,

physical therapist, psychologist, social worker, rehabilitation engineer, and

voca-tional counselor at different times as the need arises.

As the years go by, these patients also have the same

medical problems as others in the aging population. In addition, they face the

threat of complications associated with their disability. Usu-ally the patient

is encouraged to attend a spinal clinic when com-plications and other issues

arise. Lifetime care includes assessment of the urinary tract at prescribed

intervals, because there is the likelihood of continuing alteration in detrusor

and sphincter function and the patient is prone to UTI.

Long-term problems and

complications of SCI include disuse syndrome, autonomic dysreflexia (discussed

earlier), bladder and kidney infections, spasticity, and depression. Pressure

ulcers with potential complications of sepsis, osteomyelitis, and fistulas

occur in about 10% of patients. Flexor muscle spasms may be particu-larly

disabling and occur in up to 25% of patients (Sullivan, 1999). Heterotopic

ossification (overgrowth of bone) in the hips, knees, shoulders, and elbows

occurs in up to 30% of SCI patients. This complication is painful and can

produce a loss of range of motion (Mitcho & Yanko, 1999; Subbarao &

Garrison, 1999). Management includes observing for and addressing any

alter-ation in physiologic status and psychological outlook, and the prevention

and treatment of long-term complications. The nurs-ing role involves emphasizing

the need for vigilance in self-assessment and care.

Related Topics