Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: Clinical Evaluation and Treatment Planning: A Multimodal Approach

Neurophysiologic Assessment

Neurophysiologic Assessment

A variety of techniques are now available that can

provide more direct assessments of brain function in psychiatric patients.

These include not only neuroimaging techniques (PET scans and functional MRI),

but also electrophysiologic measures, such as the EEG and evoked or

event-related potentials (ERPs). Electro-physiologic measures have the

advantage of being economical and noninvasive, and allow continuous monitoring

of brain elec-trical activity with a temporal resolution that surpasses that of

neuroimaging measures. The EEG has traditionally been used in psychiatry to

screen for brain disorders. In a conventional clinical EEG, a highly trained

reader uses visual inspection of brain waves recorded from scalp electrodes.

The presence of epileptiform discharges, spikes, or generalized slowing of

brain electrical activity is associated with known central nervous sys-tem

pathology. In patients who have a history of head trauma or where epilepsy is

suspected, a clinical EEG should be done to rule out organic brain disorders

(see Table 19.10). When evalu-ating for epilepsy, several EEGs may be necessary

for accurate results because epileptiform activity is not consistently present

(Boutros, 1992). The EEG can also play an important role in the diagnosis of

dementia, delirium and other cognitive disorders. Generalized EEG slowing in

Alzheimer’s dementia is correlated with the degree of cognitive impairment and

with decreased

regional cerebral blood flow (Hughes and John,

1999). In elderly psychiatric patients, a clinical EEG is of value for

distinguishing dementia and pseudodementia associated with depression. This is

of importance for treatment selection because EEG abnormal-ity in elderly

patients is negatively associated with clinical re-sponse to antidepressants

(Boutros, 1992).

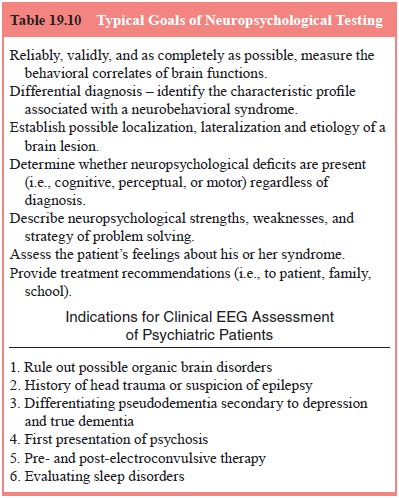

Patients who experience their first psychotic episode are also candidates for a clinical EEG because brain lesions and seizure disorders, such as temporal lobe epilepsy, can cause psychotic symptoms that are clinically indistinguishable from functional psychoses. EEG recordings before, during and after electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) for depression also have clinical relevance (Hughes, 1996; Small, 1999). Patients with pretreatment EEG abnormalities may respond less well to ECT (Drake and Shy, 1989), and changes in EEG after ECT generally accompany clinical improvement (Sackeim et al., 1996). Reviews of clinical EEG findings in childhood and adult psychiatric disorders show that 30 to 60% of referrals have abnormal EEGs (Hughes, 1996; Small, 1999), which underscores the importance of clinical EEGevaluations in psychiatry. One of the limitations of routine clini-cal EEG is that it is dependent on the trained eye of the reader and is therefore subject to human error and may miss subtle abnor-malities in the EEG tracing. Brain potentials evoked by auditory or visual stimuli (e.g., clicks or tones) have been used in both clinical and research contexts in psychiatry. Brain stem evoked potentials (BSEPs) refer to seven positive potentials evoked dur-ing the first 12 milliseconds after hearing a click. BSEPs have proven useful for assessment of hearing in infants and uncoop-erative patients, and in the assessment of brainstem lesions and multiple sclerosis (Celesia and Brigell, 1999). A later event-re-lated P3 or P300 potential, typically recorded during an “odd-ball’’ target detection task with either auditory or visual stimuli, refers to a positive potential that peaks 300 to 500 milliseconds after onset of an infrequent target stimulus. The strongest case for the clinical utility of the P3 potential is in aging and demen-tia (Polich, 1999). Longer P3 latency distinguishes patients with dementia from those with pseudodementia secondary to depres-sion, and patients with Alzheimer’s disease from healthy subjects (Ford et al., 1997; Frodl et al., 2002; Polich and Herbst, 2000). Although P3 provides a useful index of cognitive effi ciency, it has little value for the differential diagnosis of psychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia because it lacks specifi city.

Related Topics