Chapter: Basic Radiology : Radiology of the Breast

Exercise: The Palpable Mass

THE SYMPTOMATIC PATIENT

EXERCISE 5-1.

THE PALPABLE MASS

(Please answer questions for this

exercise before looking at the images, which are presented with the

discussion.)

5-1. In Case 5-1, a 34-year-old woman

who noticed a new lump in her breast, which test

should be ordered first?

A.

Screening mammography

B.

Excisional biopsy

C.

Ultrasonography

D.

Diagnostic mammography

E.

Needle aspiration

5-2. Case 5-2 is a

60-year-old woman who, on the insis-tence of her children, went for her first

routine physi-cal examination in many years. Her doctor found a mass in her

breast. Which test should be ordered first?

A.

Screening mammography

B.

Excisional biopsy

C.

Ultrasonography

D.

Diagnostic mammography

E.

Needle aspiration

5-3. In Case 5-3, a

53-year-old woman thinks she feels a hard nodule deep in her breast. Her

breasts have al-ways been difficult to examine because of their dense nodular

texture. What test should be ordered first?

A.

Screening mammography

B.

Excisional biopsy

C.

Ultrasonography

D.

Diagnostic mammography

E.

Needle aspiration

5-4. In Case 5-4, a

78-year-old woman with a soft, rounded mass discovered during physical

examina-tion, which one of the following statements is true?

A.

A 78-year-old will not likely benefit from mam-mography.

B.

Soft, rounded masses are benign and do not re-quire biopsy.

C.

This mass should initially be aspirated with a needle.

D.

If this mass is carcinoma, the patient will proba-bly die of

this disease.

E. Her physical findings could

easily be caused by a lipoma.

Radiologic Findings

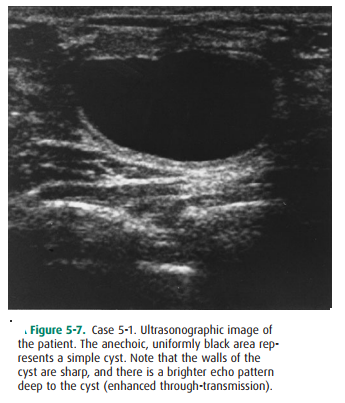

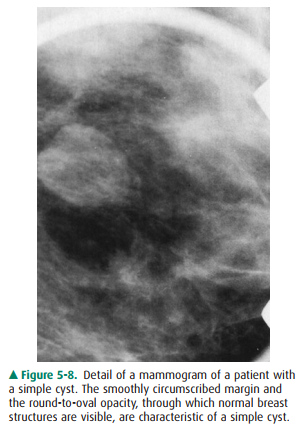

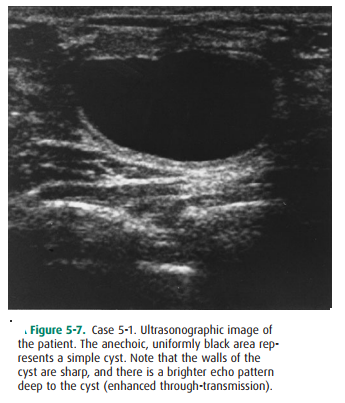

5-1. Ultrasonographic image of the patient in Figure 5-7. The anechoic, uniformly black area represents a simple cyst.

Note that the walls of the cyst are sharp, and there is a brighter echo pattern

deep to the cyst (enhanced through-transmission) (C is the correct answer to

Question 5-1). Figure 5-8 illustrates the mammo-graphic features of a cyst. The

shape is round or oval, and the margins are smooth and sharply delineated.

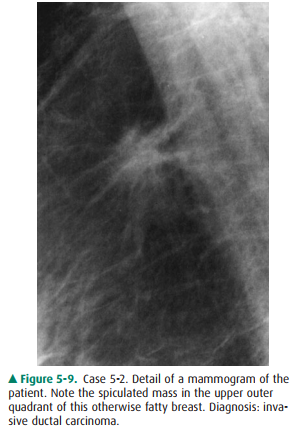

5-2. Detail of a

mammogram (Figure 5-9) of the patient in Case 5-2. Note the spiculated mass in

the upper outer quadrant of this otherwise fatty breast. Diagno-sis: invasive

ductal carcinoma (D is the correct an-swer to Question 5-2).

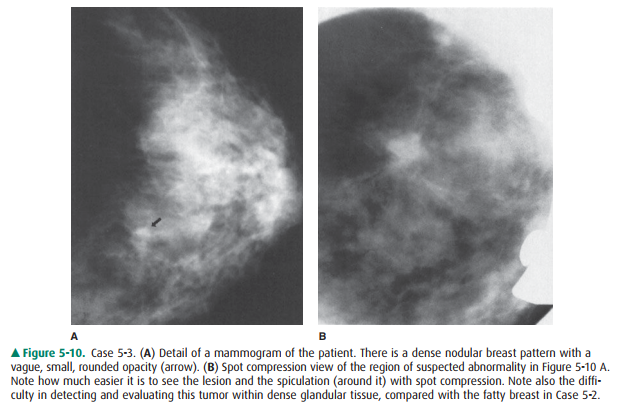

5-3. Detail of a mammogram (Figure 5-10 A) of the pa-tient in

Case 5-3. There is a dense nodular breast pat-tern with a vague, small, rounded

opacity (arrow). Spot compression view (Figure 5-10 B) of the region of

suspected abnormality in Figure 5-10 A. Note how much easier it is to see the

lesion and the spiculation (around it) with spot compression. Note also the

dif-ficulty in detecting and evaluating this tumor within dense glandular

tissue, compared with the fatty breast in Case 5-2 (D is the correct answer to

Question 5-3).

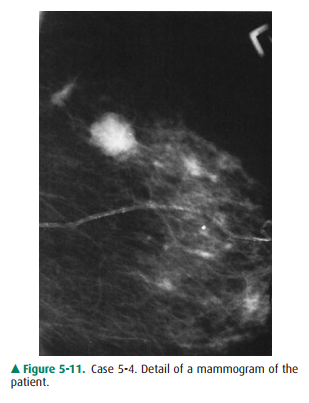

5-4. The 78-year-old

patient in Case 5-4 (Figure 5-11) has a soft mass in her breast and clearly

needs a diagnos-tic mammogram because of her age and the palpable findings (E is

the correct answer to Question 5-4).

Approach to the Palpable Lump

When a breast lump is found,

several questions must be an-swered before proceeding with breast imaging.

First, given that lumpy breasts are a normal variant, when is a lump

sig-nificant? Experts in CBE advise palpation with the flat surface of two to

three fingers, and not with the fingertips. With this technique, nonsignificant

lumps will disperse into back-ground breast density, but a significant lump

will stand out as a dominant mass.

Second, is the lump new or

enlarged? A new lump is more suspicious than a lump that has not changed over a

few years.

Third, how big is the lump? Tiny

pea-sized or smaller lumps, particularly in young women, are often observed

closely with repeated CBE, because small breast nodules are extremely common,

frequently resolve spontaneously, and are usually benign. Repeating CBE in 6

weeks allows for in-terval menses, which frequently causes waning or resolution

of the lump. If the lump persists, diagnostic mammography is indicated.

Fourth, how old is the patient?

If the patient is less than 35 years of age, then radiation is avoided unless

specifically indicated, because the younger breast is more sensitive to

ra-diation. For patients over the age of 35 years, breast imaging begins with a

diagnostic mammogram at the time a lump is deemed to be significant. The

mammogram provides a view of the lump, as well as of the remainder of the involved

breast and the opposite breast, where associated findings may aid in diagnosis

and treatment planning.

If the patient is below 35 years

of age, a significant lump is usually first examined with ultrasonography to

determine whether a simple cyst is present. If there is no cyst, and the

patient is below 30 years of age, the radiologist may choose to obtain a

mammogram, but the density of the breast in such a young patient may limit the

usefulness of radiomammogra-phy, so the mammogram may be limited to one breast

or to a single view.

For women between the ages of 30 and 40 years, judgment is needed as to whether other imaging is indicated. Several factors should be weighed, including age, family history of breast carcinoma, reproductive history, and findings at CBE. If the primary care physician is uncertain of the significance of the findings of CBE, evaluation by a breast specialist may be helpful prior to requesting radiologic tests.

Discussion

The 34-year-old woman in Case 5-1

indeed has a dominant mass, 2 cm in diameter on CBE. She says it was definitely

not present until recently. She has no risk factors for breast can-cer. The

mass most likely is a fibroadenoma or a cyst, but car-cinoma cannot be

excluded. The patient now needs breast ultrasonography.

Ultrasonography is best ordered

before attempted needle aspiration because aspiration can alter the appearance

of simple cysts, giving a misleading suspicious appearance. Therefore, answer

E, needle aspiration, is incorrect.

Figure 5-7 shows an image from

the ultrasound study that represents the area precisely in the location of the

pal-pable mass. This area is echo-free, with sharply delineated walls and

posterior acoustic enhancement (increased echogenicity deep to the anechoic

area) consistent with a simple cyst. If these three features are seen, the

probability of a simple cyst is greater than 99% and no further treat-ment is

indicated unless the patient has pain and needs cyst drainage for symptomatic

relief. Therefore, option B, exci-sional biopsy, is inappropriate, because

biopsy can be avoided by showing a simple cyst. No further imaging is needed.

The patient is under the age of 40 years, not yet of screening age, and

radiation should be avoided in young patients. Therefore, answers A and D,

screening and diag-nostic mammography, are not viable options until ultra-sound

is performed.

Simple cysts are very common in

the premenopausal pa-tient and in patients who are being treated with hormone

re-placement therapy. A complex cyst is one that has internal debris—blood,

pus, or tumor. A complex cyst requires fur-ther evaluation, and a short-term

follow-up (6 to 8 weeks) ultrasound may be sufficient. If the debris is due to

attempted aspiration, it may clear on follow-up ultrasonography. Oth-erwise,

excision or needle biopsy is indicated.

The 60-year-old woman in Case 5-2

has a 1.5-cm domi-nant mass on CBE. It is irregular and not freely mobile. The

patient has never had a mammogram. Because she has a pal-pable mass, however, a

screening mammogram is inappro-priate, and option A is incorrect. Although the

mass feels suspicious, she still needs a diagnostic mammogram prior to biopsy

(option B, excisional biopsy, is incorrect), to exclude other lesions such as

multifocal carcinoma. The need for ul-trasonography in a patient of this age is

dictated by the mam-mographic appearance; therefore, option C, ultrasonography,

is incorrect.

Her mammogram (Figure 5-9) shows

a very fatty breast, making any abnormal findings readily apparent. There is a

mass measuring 1 cm in the upper outer quadrant that corresponds to the area of

the palpated mass. The mass is of high density, being white on the mammogram.

There is abundant spiculation and stranding around the mass that is represented

by the radiating linear densities around the pe-riphery of the mass. There is

also retraction of the linear patterns of the normal breast tissue; this

retraction is known as architectural distortion. These findings represent the

classical features of a malignant lesion on mammogra-phy, and this mass must be

biopsied. A spiculated mass such as this is the most common appearance of

invasive breast carcinoma. Less common signs are a circumscribed mass, asymmetric

density, and architectural distortion alone. In-traductal (noninvasive)

carcinoma is more commonly asso-ciated with calcifications.

Spiculation around an invasive

carcinoma corresponds to fingers of tumor, as well as to a desmoplastic

reaction of ad-jacent normal breast tissue responding to the presence of tumor.

This patient has an invasive ductal carcinoma. About 90% of primary breast

carcinomas are ductal carcinomas, and the other 10% are lobular carcinomas.

Besides carcinoma, the primary

differential diagnosis for a spiculated mass includes postsurgical change,

other trauma with hematoma, fat necrosis, infection, and radial scar (a

complex, spontaneous benign lesion involving ductal prolif-eration, elastosis,

and fibrosis).

There are no other lesions in our

patient’s breast, and the other breast appears normal. By mammographic

criteria, then, the patient is a good candidate for treatment with lumpectomy

and radiation therapy rather than mastectomy. Her tumor is solitary, localized

to one quadrant, and her breast tissue is otherwise easy to evaluate

mammographically. Recurrent tumor or additional lesions should, therefore, be

readily seen on posttreatment follow-up mammograms.

For a mass that feels malignant

and appears suspicious on a mammogram, fine-needle aspiration (FNA) at the

bedside may provide a rapid cytological diagnosis of carcinoma. Be-cause FNA

best follows mammography, option E, needle as-piration, is incorrect. FNA may

then be followed by definitive surgical treatment at a later date, after the

patient has had time to consider the treatment options available. If FNA fails

to disclose carcinoma, then excisional biopsy is required be-cause of the

suspicious findings on mammography and CBE. The occasional false-negative FNA

occurs with tumors that do not shed cellular material readily.

Cytology of this palpable mass

revealed ductal carcinoma, and this patient chose to have a lumpectomy.

The 53-year-old patient in Case

5-3 has an ill-defined 1.5-cm hardened nodular area in her breast. Results of

screening mammography less than 1 year ago were normal. Her breast tissue is

not fatty, as in Case 5-2, but she has quite dense, nodular, fibroglandular

tissue, which may ob-scure small masses. The average doubling time of breast

carcinoma makes it unlikely that she has a palpable carci-noma that is entirely

new since her last mammogram. It is quite possible, however, that she has had a

smaller cancer for a few years and that it has now grown large enough to be

palpated. Breast tumors are typically not palpable unless they are at least 1

cm in diameter. Before this stage, in the preclinical phase, the tumor may be

visible up to 2 or 3 years earlier on the mammogram if the breast is fatty. In

dense breasts, as discussed previously, tumors may not be seen on the mammogram

until later stages. For this reason, regular CBE is important. Mammography will

miss some cancers, regardless of the situation, at a rate variably reported to

be between 5% and 15%.

With a new area of abnormality on

physical examina-tion, being in a high-risk age group (over 50 years old), and

having a dense parenchymal pattern, the patient needs another mammogram, this

time a diagnostic mammo-gram of the involved breast only. Option A, screening

mammogram, is incorrect, because it is too soon to repeat screening mammography

at this time and the patient does have a palpable finding—a contraindication

for a screen-ing study.

Figure 5-10 A shows a vague,

rounded opacity within dense fibroglandular tissue. This is in the area of the

palpable mass, as indicated by a small BB placed on the skin over the

abnormality. Detail is not adequate to make a judgment as to the possibility of

malignancy here, or even to confirm that a real lesion is present. The

appearance may merely be due to superimposed normal breast shadows. Compression

spot films are needed to confirm the presence of a mass and to better define

its borders.

Figure 5-10 B shows spot

compression of the questioned opacity seen on initial images. This localized

compression with a smaller paddle placed directly over the abnormality achieves

two things. First, it separates the opacity from adja-cent breast tissue,

demonstrating this to be a discrete mass with high density and not merely

superimposition of normal shadows. Second, it elicits clear spiculation and

architectural distortion around the mass. These features are classic for breast

carcinoma, and biopsy is therefore required. Biopsy of this lesion showed

invasive ductal carcinoma.

The 78-year-old patient in Case

5-4 has a soft mass in her breast and clearly needs a diagnostic mammogram

because of her age and the palpable findings. Soft, rounded masses on physical

examination are often benign fibroadenomata or cysts, but carcinoma may also

present this way (Statement B is false).

Other benign causes of these physical findings include hematoma, abscess, and lipoma (Statement E is true). There-fore, a mammogram may be beneficial for two reasons: (1) if a benign finding is revealed, biopsy may be avoided; and if findings suggest malignancy, optimal treatment can be planned on the basis of extent of the lesion and presence or absence of additional lesions (Statement A is false).

Her mammogram (Figure 5-11) shows

two findings. There is a rounded mass with multiple lobulations and cir-cumscribed

borders. The fact that the borders are not sharply outlined on all sides raises

the suspicion level for this finding. Masses that are sharply delineated may be

followed with serial mammograms at 6-month intervals if they are known not to

be new, are nonpalpable, and show no other features of malignancy. This is not

the case with the patient in Case 5-4. Note the fading margin along portions of

the mass. This mass corresponds to the palpable finding. Ultra-sonography would

be useful to exclude a multiloculated cyst and show the lesion to be solid.

Biopsy is indicated, but nee-dle aspiration without imaging would have been

inappropri-ate (Statement C is false).

A circumscribed mass representing

carcinoma is seen less often than a spiculated mass. About 10% of invasive

ductal carcinomas represent the better-differentiated subtypes, in-cluding

medullary carcinoma, mucinous (colloid) carci-noma, and papillary carcinoma,

all of which are frequently seen as circumscribed masses. They tend to have a

better prognosis than the less well-differentiated garden-variety ductal

carcinomas.

The differential diagnosis for

the circumscribed mass on mammography includes carcinoma (primary as well as

metastatic), fibroadenoma, and cysts; hematoma, abscess, and miscellaneous

benign lesions are seen much less often. Correlation with clinical history and

physical examination can help to narrow the differential diagnosis. When

carci-noma cannot be excluded, either needle aspiration or exci-sional biopsy

is required.

This patient had a needle biopsy.

Because palpation alone could not reliably localize this lesion for needle

biopsy be-cause of its soft nature and the difficulty in fixing its posi-tion,

stereotactic mammographic guidance was used in localizing the lesion for this procedure.

The diagnosis of mu-cinous carcinoma was made by microscopic inspection of the

specimen.

Now, were you astute enough to

perceive the second le-sion? Above and to the left of large mass is a smaller,

dense spiculated mass. This was also biopsied and proved to be a carcinoma of

the very well-differentiated tubular type. Even though the patient has two

lesions now, both carry an excel-lent prognosis and they are unlikely to cause

her death (State-ment D is false). In fact, although mastectomy is certainly a

reasonable treatment for her, local excision would also be an option with these

nonaggressive lesions.

Related Topics