Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: The Cultural Context of Clinical Assessment

Working with Interpreters and Culture-brokers

Working with Interpreters and

Culture-brokers

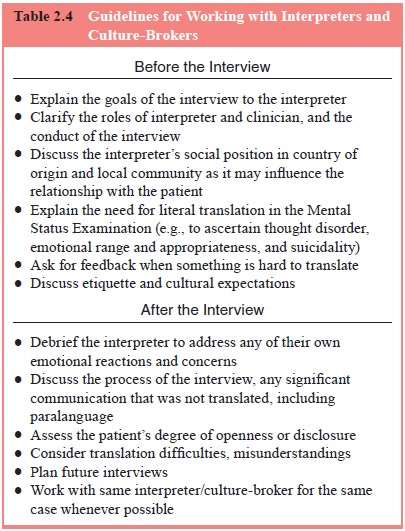

A key skill which has not been addressed in many

training pro-grams concerns how to work with interpreters (Table 2.4). In the

absence of familiarity with this technique and quality assur-ance standards

insisting on appropriate use of interpreters, many clinicians simply try to

avoid the situation, relying on patients’ sometimes limited command of the

clinician’s language. This is unfortunate and may lead to errors in diagnosis

and management as well as the failure to engage and help many patients.

There are several models of working with

interpreters (Westermeyer, 1989). Medical interpreters have adopted a code of

ethics and model of working that owes much to forensic and political

interpreting. Their goal is to provide accurate, complete and literal

translation of the statements of patient and physician. This model tends to

portray the interpreter as providing a trans-parent window or conduit of

communication between clinician and patient. In this approach, the clinician

addresses the patient directly as though the interpreter is not present. The

interpreter may speak in the first person for the patient and for the clinician

alternately. The model assumes that it is possible to achieve com-plete and

accurate translation of message in both directions and treats the interpersonal

triad of doctor–interpreter–patient as if it was a dyad. To do so assumes that

the interpreter does not have an independent relationship with patient or

clinician. Of course, this is certainly not the case in any clinical encounter

that goes on for a time or involves repeated meetings. Indeed, at the level of

transference it is never the case because the mere presence of another person

immediately evokes distinctive thoughts, feelings

Table 2.4 Guidelines

for Working with Interpreters and Culture-Brokers

Before the

Interview

·

Explain the goals of the interview to the interpreter

·

Clarify the roles of interpreter and clinician, and the

conduct of the interview

·

Discuss the interpreter’s social position in country of

origin and local community as it may influence the relationship with the

patient

·

Explain the need for literal translation in the Mental

Status Examination (e.g., to ascertain thought disorder, emotional range and

appropriateness, and suicidality)

·

Ask for feedback when something is hard to translate

·

Discuss etiquette and cultural expectations

After the

Interview

·

Debrief the interpreter to address any of their own

emotional reactions and concerns

·

Discuss the process of the interview, any significant

communication that was not translated, including paralanguage

·

Assess the patient’s degree of openness or disclosure

·

Consider translation difficulties, misunderstandings

·

Plan future interviews

·

Work with same interpreter/culture-broker for the same case

whenever possible

and fantasies. Then too, the presence of the

interpreter inevitably changes a dyad into a triadic social system with its own

complex interpersonal dynamics. These dynamics are complicated by the

ethnocultural background of the interpreter and his or her own cultural

assumptions.

The very idea of literal translation is also

problematic. Across languages, words and phrases with similar denotation often

have different sets of connotations. Every translation, there-fore, is an interpretation

that emphasizes some potential mean-ings while muting or eliding others.

Interpreters tend to smoothe out fragmentary, incomplete, or incoherent

statements and so may mask thought disorder or other idiosyncrasies of speech

with diagnostic relevance. The clinician needs to understand the choice of

alternatives made by the interpreter in order to appre-ciate the connotations

of the patient’s words and to convey his or her own nuanced meanings. These

requirements place much higher demands on interpreting in mental health setting

than in other medical or legal settings.

A slightly different model views the interpreter as

a “go-between”. In this approach, the interpreter takes turns interact-ing with

clinician and patient to clarify what is being said and to find a means of

conveying it. This model acknowledges the interpreter as an active intermediary

and allows the interpreter some autonomy. The sequential dyadic interaction

puts greater time and distance between clinician and patient. This demands that

the interpreter have a high degree of clinical knowledge and interpersonal

skill, which is possible when the interpreter has been trained as a clinician.

Taking this autonomy further, the in-terpreter may be viewed as a cotherapist.

In this approach, the interpreter with clinical skills develops his or her own

working alliance with the patient. The interpreter may respond independ-ently

to the patient and initiate interventions. This sometimes happens because of

language barriers, when patients may contact the interpreter to ask for help

with practical issues.

Given the complexities of interpreting, we prefer

to view the interpreter as a culture-broker who works to provide both the

patient and the clinician with the cultural context needed to understand each

other’s meanings. To do this, the interpreter must understand something of the

perspectives, cultural back-ground and social positions of both patient and

clinician and appreciate the goals of the clinical task. Based on this

knowl-edge, the culture-broker can enhance patient and clinician un-derstanding

of each other and can help negotiate compromises when there are widely

divergent understandings of a problem and its solutions.

Despite increasing recognition of the importance of

ad-equate interpretation, many clinicians or institutions use lay in-terpreters

who are directly available at no cost, usually family members (even children)

or other workers within the institution. Except in emergency situations, this

practice should be avoided because it exerts a strong censorship on what may be

disclosed in the encounter and because it may damage relationships that are

very important to the patient by transgressing certain social and familial

taboos.

Both interpreters and culture brokers need training

to per-form competently, and clinicians need training, in turn, to work with

these allied professionals. The clinician must take a sys-temic approach,

understanding the other people in the room as part of an interactional system.

Clinicians must also understand the interpreter’s position in the larger

community. Some of this training can go on when clinicians have an opportunity

to work repeatedly with the same interpreters, who thus become part of a

treatment team.

Related Topics