Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: The Cultural Context of Clinical Assessment

Illness Explanations and Help-seeking

Illness Explanations and

Help-seeking

The second major dimension of the cultural

formulation concerns cultural explanations of symptoms and illness. Cultures

provide systems of diagnosis and treatment of illness and affliction that may

influence patients’ experience of illness and help-seeking behavior. People

label and interpret their distress based on these systems of knowledge, which

they share with others around them. Much

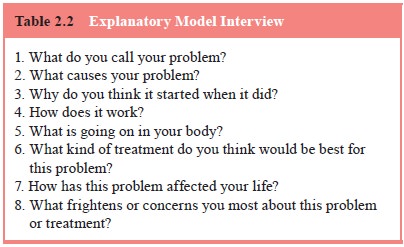

Table

2.2 Explanatory Model Interview

1. What do you

call your problem?

2. What causes

your problem?

3. Why do you

think it started when it did?

4. How does it

work?

5. What is going

on in your body?

6. What kind of

treatment do you think would be best for this problem?

7. How has this

problem affected your life?

8. What frightens

or concerns you most about this problem or treatment?

research in medical anthropology has developed the

idea of ex-planatory models, which may include accounts of causality,

mecha-nism or process, course, appropriate treatment, expected outcome and

consequences. Not all of this knowledge is related directly to personal

experience – much of it resides in cultural knowledge and practices carried by

others. Hence, understanding the cultural meanings of symptoms and behavior may

require interviews with other people in the patient’s family, entourage, or

community.

Table 2.2 provides questions for eliciting

patients’ explan-atory models. These questions should be modified based on the

patient’s responses. For example, the origins of problems may be located not in

the body but in the workings of the mind, the family, the community, the realms

of ancestors or spirits, or in mythological accounts that explain the social

and moral order.

In many cases, particularly with acute illness,

patients may not have well-developed explanatory models. Instead, they reason

by analogy on the basis of past experiences of their own or other prominent

prototypes encountered in family, friends, or mass media. Once an explanatory

model is evoked in conver-sation, however, patients may give formulaic accounts

that ac-cord with that cultural model or script. Therefore, to obtain more

complete information about the cognitive and social factors that are actually

influencing the patients’ illness experience and be-havior, it is useful to

begin with an open-ended interview that simply aims to reconstruct the events

surrounding symptoms and the illness experience. This will reveal idiosyncratic

temporal patterns of contiguity and association that may not fit any explicit

cultural model. Following this, the clinician can ask about proto-types (Have

you ever had anything like this before? Has anyone you know ever had anything

like this before?) This will uncover salient models of illness that may shape

illness experience and be used to reason analogically about the current

episode. Finally, it is important to inquire into explicit cultural models

using the sorts of questions devised for the explanatory model interview.

The ethnomedical systems described in

anthropological texts often are idealized and complex portraits pieced together

by working with cultural experts. In clinical practice, patients usually have

only partial or fragmentary knowledge of the tradi-tional explanations and

treatment for their problem. Depending on the knowledge and attitudes of family

and kin, and on the availability of practitioners of traditional medical

systems, pa-tients may be influenced by larger cultural systems to which they

themselves do not fully subscribe.

In everyday life, people use culturally prescribed

idioms to discuss their problems. These cultural idioms of distress cut across

specific diagnostic categories. They may be used to talk about ordinary

problems as well as to shape the expression of distress associated with major

psychiatric disorders. For exam-ple, many cultures have notions of “nerves” (in

Spanish, nervios), which signal

emotional distress that may range from mild upset with life events to disabling

anxiety or psychosis. Appendix I of DSM-IV-TR provides a list of some common

idioms of distress. The same appendix also lists some well-described culture

bound syndromes, culturally distinctive clusters of symptoms that may be of

pathological significance. Many culture-specific terms, however, do not refer

to syndromes or idioms of distress but are actually symptoms or illness

attributions that reference folk models of causality. For example, susto, a term used in Central and South

America, attributes a wide range of bodily symptoms and diseases (including

infectious diseases and congenital mal-formations) to the damaging effects of

sudden fright.

Many cultural idioms of distress use bodily

metaphors for experience. In seeking medical help, patients usually try to

present the sort of problems they believe the clinician is com-petent to treat.

Consequently, in biomedical settings patients tend to emphasize physical

symptoms. This pattern of clinical presentation combined with the wide currency

of somatic idioms of distress has led to a characterization of many

ethnocultural groups as prone to somatize their distress (Kirmayer, 2001). The

social stigma commonly associated with psychiatric symptoms and disorders, as

well as with substance abuse, antisocial behav-ior and various other behaviors

also may prevent patients from acknowledging such problems and events. However,

with clear communication and a respectful stance, the clinician may be able to

build sufficient trust over time for patients to disclose shame-ful or

potentially stigmatizing information.

Similarly, people commonly use multiple remedies or

con-sult various healers for their symptoms, and may be reluctant to disclose

treatments they think the clinician will not understand or accept. They may

also omit mention of preparations they view as “natural” or as foods and hence

not included under the rubric of medications or drugs. Commonly used remedies

like ginseng, St John’s Wort and Gingko

biloba have significant effects on pharmacokinetics and drug metabolism and

are, therefore, important for their potential impact on physiology as well as

their role in patients’ belief systems and sense of control over their illness.

A nonjudgmental inquiry by the clinician willenable patients more freely to

discuss their use of traditional and alternative treatments.

Related Topics