Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: The Cultural Context of Clinical Assessment

Culture and Gender

Culture and

Gender

Gender refers to the ways in which cultures

differentiate and define roles based on biological sex or reproductive

func-tions. Because of this link with physical aspects of sex, there is a

tendency to view gender differences as biological givens. However, while some

distinctions may be closely related to the physiological differences between

males and females, most are assigned to the sexes on the basis of specific

cultural beliefs and social organization (Comas-Diaz and Greene, 1994).

Men and women do have some fundamentally different

experiences of their bodies, of their social worlds and of their life course.

It has been suggested that women are more in touch with their bodies because of

the experiences of menstruation, child-bearing, childbirth, breast-feeding and

menopause. These differ-ences may be as substantial as any between disparate

cultures. At the same time, there is much evidence that these bodily grounded

experiences vary substantially across cultures. For example, the anthropologist

Margaret Lock (1993) has shown that Japanese women report fewer bodily symptoms

of menopause and do not think of the end of menstruation as a distinctive

“change of life” in the same terms as many women in North America.

There are also important gender differences in

styles of emotional expression, symptom experience, and help-seeking. In

epidemiological surveys in the USA, women tend to report more somatic symptoms

as well as more emotional distress and they are more likely to seek help for psychological

or interpersonal prob-lems. However, the gender difference in symptom reporting

var-ies significantly cross-nationally (Piccinelli and Simon, 1997).

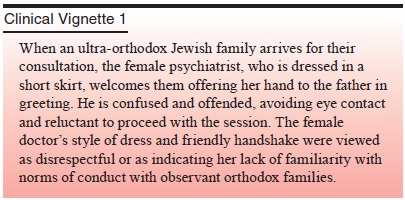

In North America, important differences have been

docu-mented in male and female styles of conversation that are rel-evant to the

clinical context (Tannen, 1994). In general, women tend to give more frequent

acknowledgments that they are listen-ing to a speaker. They may give signs of

assent simply to indicate they are following the conversation. Men tend to be

more taciturn and, if they signal assent, it usually means they actually agree

with the speaker. These differences in communication style may lead to

systematic misunderstandings between men and women that are further aggravated

by cultural differences in gender roles and etiquette.

In many societies, gender is associated with marked

dif-ferences in power and social status. For example, in patriarchal societies,

men have specific power and privileges that give them a measure of control over

the lives of women. This is often coupled with responsibilities for maintaining

family honor and well-being. In recent years, North American society has

es-poused social and political equality in gender roles. From this egalitarian

point of view, patriarchal families may seem oppres-sive to women. However,

women may accept and participate in cultural definitions of their roles that

appear restrictive by North American cultural norms but that make family life

meaningful. Any judgment as to whether a given family’s relationships are

oppressive or pathological must not only take into account social norms and

practices but also explore the meaning of issues and events for the individuals

involved.

Differences in cultural definitions of gender roles

may be-come sources of conflict after migration. Culturally prescribed patterns

of marriage and child bearing may be central to the social status, identity and

self-esteem of men and women even when they are not given the same importance

in the dominant cultures.

Related Topics