Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: Group Psychotherapy

Theories of Group Therapy

Theories

of Group Therapy

The

theoretical spectrum informing the practice of group therapy is broad. Within

psychodynamics, some emphasize drive theory, object relations, or

self-psychology. Other therapists favor inter-personal theory and

cognitive–behavioral approaches. Transac-tional analysis, originating from the

work of Berne (1966), and Gestalt therapy (Perls et al., 1951) emphasize interpersonal trans-actions arising from

more traditional psychodynamic theory.

Group

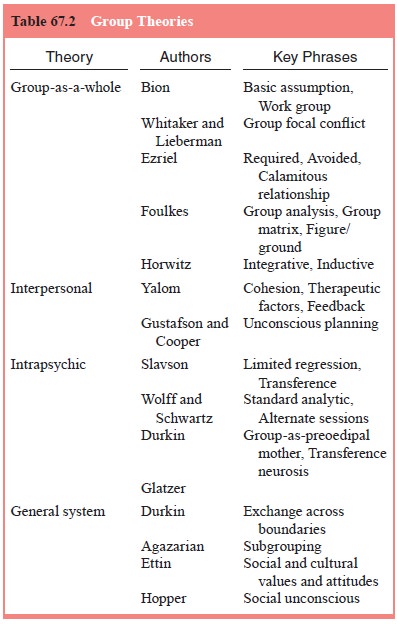

theoreticians are generally categorized along a continuum of group as a whole,

interpersonal and intrapsychic. Moreover, therapists using object relations,

self-psychology or psychodynamic theories integrate their theoretical

preferences along this continuum (Kibel, 1992; Harwood and Pines, 1998; Rutan

and Stone, 2001). There are few purists and varying de-grees of integration is

the norm (Table 67.2).

A common

thread in many of these theories is that indi-viduals in their interaction and

discourse within the group will exhibit their difficulties in relationships,

which in turn provides a window into their internal world. In short, the group

becomes a microcosm of their external world (Slater, 1966).

Group-as-a-Whole Approaches

These

theories emphasize whole-group processes as the pri-mary therapeutic vehicle.

They subscribe to notions that mem-bers are influenced by the group dynamics and

that one or more persons may speak for the entire group, including those who

are silen

Interpersonal Approaches

On the

basis of Sullivanian principles, Yalom (1995) empha-sized the centrality of

transactions in the here and now of the group as the primary, but not

exclusive, therapeutic force for change. His formulation of “therapeutic

factors” brought into sharp focus the importance of cohesion (which is a

dynamic concept that implies that the group is attractive, “safe”, and that members

have a commitment to the group goals and ideals). Yalom pays particular

attention to members’ capacity to give and receive feedback. He asserts that

maladaptive interpersonal transactions are the consequence of parataxic

distortions (hav-ing some similarity to transference responses, i.e., arising

from childhood experiences) that can be therapeutically altered by authentic

human interaction, that is, feedback and consensual validation.

Intrapsychic Approaches

Intrapsychic

theories are primarily application of dyadic theory into the group setting. The

emphasis is on unconscious proc-esses with the group providing opportunities

for patients to regress to a level of internal conflict or developmental

arrest. These theories explore individual transferences, resistances and

developmental arrests as the primary therapeutic focus. Peers may be

experienced as siblings or as displacement objects from parental figures

(Slavson, 1950; Wolf and Schwartz, 1962). Groups may either dilute or intensify

transferences to the leader (Horwitz, 1994), which enables “stuck” patients to

resolve im-passes occurring in dyadic treatment. Regression is limited, and the

presence of others creates a balance between the external and the internal

worlds (Durkin, 1964). Integration of an in-trapsychic framework with that of

the group as a whole is con-tained in descriptions of members’ transferences to

the group as a preoedipal maternal experience (Glatzer, 1953; Scheidlinger,

1974).

General Systems Approaches

General

systems theory is based on open systems theory (von Bertalanffy, 1966).

Emphasis is placed on the boundaries separat-ing the group from the external

world and members or subgroups from one another (Durkin, 1981). Emphasis on

boundaries as worthy of therapeutic concern is evident in the group agreement.

Agazarian (1997) elaborated systems concepts into a model of group treatment

that focused on subgroups as the primary site of therapeutic attention. She

asserted that by focusing on sub-groups, which contain individual differences

and similarities, members are more prepared to address intrapsychic defenses

and resistances.

Related Topics